For nearly 30 years, Professor Colin G. Calloway — the John Kimball, Jr. 1943 Professor of History and Professor of Native American Studies — has expanded the field of Native American History at Dartmouth. Calloway, however, is aware of the baggage associated with “Native American history” in relation to “American history.” In The Indian World of George Washington, he attempts to bridge both together, presenting American history as one dependent on Native American History through the lens of President George Washington. Calloway examines the relationships between the diverse groups of Native Americans and Washington, and ultimately the foundation and early development of the United States. Calloway also describes how America’s early Indian policies influenced the way in which the executive branch’s constitutional duties are interpreted. Calloway proceeds in a chronological manner — a wise choice considering the depth of the material — allowing the common reader to easily follow along. The relationship between the Native Americans and Washington is one with many twists and turns, with victims and perpetrators on both sides. Calloway claims that Washington, influenced by his years as a land speculator, built a country on Indian land. Washington would die “one of the richest men in America, with his wealth being tied up in land he had spent more than forty years accumulating.” But Calloway states that his purpose is neither to whitewash nor demonize Washington. He does this by presenting a balanced book, filled with well-integrated sources and quotations, and a keen sense for analyzing the underlying currents of the time. To leave this book without a changed perspective in America’s early history is to not have read the book at all.

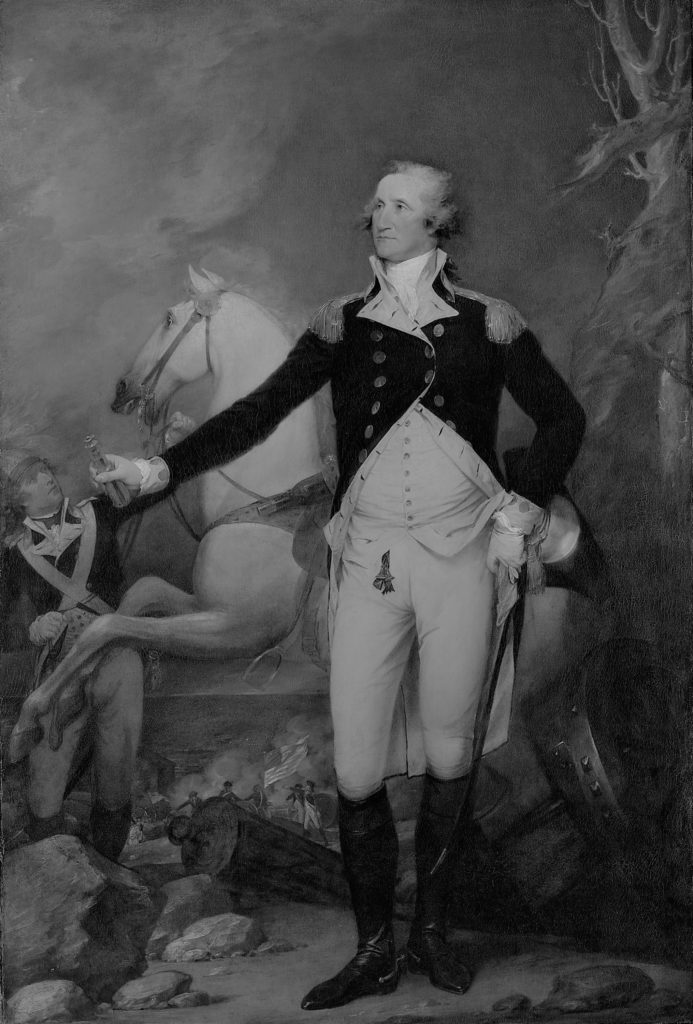

Calloway’s writing is neither flowery nor stale. Instead, he strives for historical accuracy, which he does excellently. The book is split into three parts, “Part One: Learning Curves,” “Part Two: The Other Revolution,” and “Part Three: The First President and The First Americans.” None of the sections are especially long, and Calloway presents great detail, using pictures, maps, and diagrams throughout. He also includes a considerable collection of images that enables the reader to visualize the people and places involved. Both the structure and writing style of the book are suitable and would do many a great favor in demonstrating how to write a history book that is digestible and not flamboyant.

Image Courtesy of Metropolitan Museum of Art

Both the Native Americans and Washington are given their due introductions. While some readers might think this is an autobiography of Washington with some Indian elements thrown in, it is not. Instead, it simply uses Washington as an anchor and — considering Washington’s instrumental influence in establishing America — as a metonym for America itself. From Washington’s early interactions with Native Americans until his death, he was always learning about Indian diplomacy which informed his approach to foreign policy. At the beginning of his career, Native Americans rather than Washington, held the upper-hand in the relationship. This was most evidenced by his dealings with the French, where he had to secure Indian allies in order to successfully achieve his mission. The Indians were not easily fooled and had their own diplomatic methodology. They too were nationalists, and always sought to preserve their sovereignty, leading to changing alliances with France, England, Spain, and in the future, the United States.

The French and Indian War, or the Seven-Years War, broke out due to Tanaghrisson, a Seneca. “‘In reality,’ concluded [David] Dixon, ‘it was an aged Seneca sachem who began the first of the World Wars,’” and furthermore it was “an aged Seneca” who created the circumstances in which Washington was to earn his fame in the French and Indian War. However, his lack of experience during the war also led to blunders, most notably the surrender of Fort Necessity. Calloway also notes that it was here, in Washington’s dealings with Indians, that the virtues of the future president were first exemplified. His dealings with Indians also caused Washington to realize the grave positioning of America at the time of its founding. To put it simply, they were surrounded: the English to the North and on the seas, the Spanish to the South and later the Southeast, the French to the North and West, and with the Indians along the Western border. For the young nation to survive, Calloway observes, it needed to secure its borders. It is here where the Indians played a huge role, albeit indirectly, in the interpretation of the Constitution.

Due to the precarious nature of border security, America needed to negotiate treaties with the surrounding nations. The first treaty America negotiated was with the Creeks in the South. Article II of the Constitution allows the president, with “advise and consent of the Senate,” to negotiate treaties. Washington and his advisors interpreted this as actively working with the Senate during the negotiation of the treaty, meaning that writing treaties was interpreted as a collaborative effort between the executive branch and the legislative branch. However, Washington’s visit to the Senate was so disastrous — partly because the Senate was dumbfounded by his presence — that Washington vowed to never ask for their input ever again. Because of this treaty with the Creeks, the president gives the finalized treaty to the Senate, and the treaty drafting process remains an uncooperative one. Another event that revolutionized the checks and balances of the government is when Washington asked for an expedition in the Northwest territory to enforce order in newly gained territory. However, this territory was anything but empty, as when the British gave this territory to the Americans in the Treaty of Paris, they gave a territory that belonged to Native Americans. When the United States Army marched in, they were attacked by surprise and the resulting battle ended in a complete disaster, infamously called St. Clair’s Defeat, and was labelled as America’s worst defeat. The fiasco was so calamitous that this led to the first investigation of the executive branch by the legislative branch. For a while, Washington’s advisors sought to claim what is now known as “executive privilege” in the name of “national security” in order to prevent the executive branch from being found guilty of anything. However, Washington ended up producing the documents, and the investigation did not result in any sort of punishment, but rather declared that there was a lack of judgement somewhere along the hierarchy. The controversial privilege was first conceived in the aftermath of an American defeat to Native Americans.

Given that troops were underprepared, this showed America that it needed a standing military, and thus it needed a stronger federal government. Calloway then proceeds to discuss how the creation of this strong federal government was spearheaded by Hamilton, who shared many of Washington’s views. This strong federal government, responsible for levying taxes and raising an army, was also done in order to push for Indian lands where diplomacy had failed. More interestingly, this also created a rift between northern and southern states, and between state governments and the federal government. At the time of St. Clair’s defeat, many Southerners asked themselves why Washington had sent troops to secure the Northern border, but not the Southern border. These debates were also amplified by the question of expansion, which, while having Washington’s full support, at times was at odds with the Indian policies of some states. It is not a great leap, therefore, as Calloway implies, that Native Americans played a considerable role in the development of federalism in early America.

Calloway provides a unique historical insight to the men in the book, by presenting diary entries where they ask themselves, or at least question, how these events will be portrayed in the future. These thoughts are reminiscent of what Irving Kristol said in “The American Revolution as a Successful Revolution.” “We are arrogant and condescending toward all ancestors because we are so convinced we understand them better than they understood themselves,” spoke Kristol at an AEI lecture series for the Bicentennial of the United States. Calloway shines a light on the thoughts of Henry Knox, first Secretary of War and close advisor to Washington on the Native treaties, who wrote in his diary that the result of a violent seizure of Indian lands would lead to “a stain on the national reputation of America.” But perhaps, the most relevant reflection that Knox wrote was the following: “The United States may have the verdict of mankind against them; for men are ever ready to espouse the cause of those who appear to be oppressed provided their interference may cost them nothing.” The fact that these men themselves reflected upon their policies and their legacies, allows readers and historians to view these men as people rather than just historical figures.

The Indian World of George Washington contributes greatly to the growing national discourse on the morality of the actions by George Washington, his circle of advisors, and his successors. As Calloway notes, however, Washington did share a vision for the collaboration of Indians and Americans, which while it involved the destruction of Indian identity, also provided an exit for communities who were dying. A more idealistic policy, “the nation-to-nations relationship between the federal government and Indian tribes today,” Calloway notes, “resembles that which Washington, in many of his writings and some of his policies, aspired to establish.” At no point in the book did Calloway entangle himself in tying the contents of the book with current debates. Yet, in reading the book, Calloway expertly allows the readers to form their own conclusions, no matter how difficult those might be in the end.

Apparently Jefferson was sort of his protégé – the letters that they wrote each other and others tell a very different story than I was indoctrinated in as a boy. It is strange to see how willing Washington was to cave on his ideals, and how distorted a picture our propaganda machine manufactures for us.