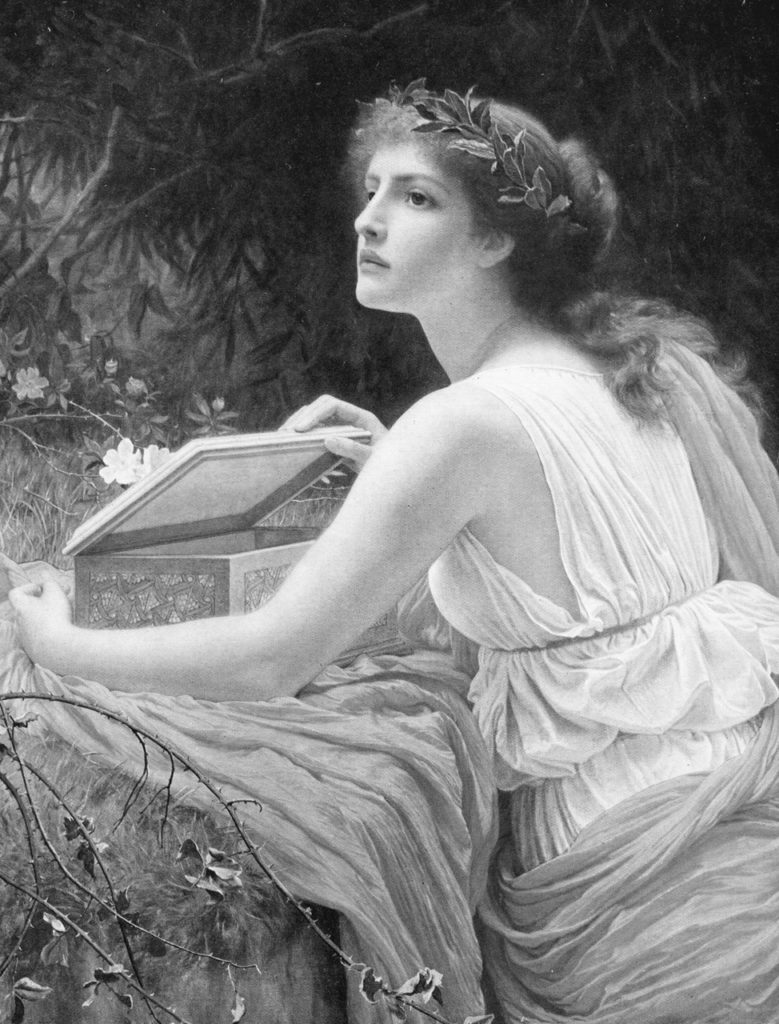

The gods had hidden away the true means of livelihood for humans. If it were otherwise, it would be easy for you to do in just one day all the work you need to do, and have enough to last you a year, idle though you would be… And he, Zeus, hid fire. But, deceiving Zeus again, the good son of Iapetos, Prometheus, stole it for humankind from Zeus the Planner inside a hollow fennel-stalk, escaping the notice of Zeus the Thunderer. Angered at him, Zeus, the cloud-gatherer, spoke: “Son of Iapetos, knowing more schemes than anyone else, you rejoice over stealing the fire and deceiving my thinking. But a great pain awaits both you and future mankind. To make up for the fire, I will give them an evil thing, in which they may all take their delight in their hearts, embracing this evil thing of their own making.” … Father Zeus to Epimetheus sent the famed Argos-killer, the swift messenger of the gods bringing the gift. Nor did Epimetheus take notice how Prometheus had told him to never accept a gift from Zeus the Olympian, but to send it right back, lest an evil thing happen to mortals. But Epimetheus accepted it, and only then did he take note that he had an evil thing on his hands. But Pandora took the great lid off the box and scattered what was inside. She devised baneful anxieties for humankind. The only thing that stayed within the unbreakable contours of the box was Hope. It did not fly out… But as for other things, countless baneful things, they are randomly scattered all over humankind. Full is the earth of evils, full is the sea. Diseases for humans are a day-to-day thing. Every night, they wander about at random, bringing evils upon mortals silently—for Zeus had taken away their voice.

So goes Hesiod’s telling of the story of Pandora’s Box in Works and Days. Prometheus, in order to make human life more bearable, steals fire from the gods. Zeus, angered by this action, seeks to punish Prometheus and his beloved humans. He knows, however, that he will not be able to outwit Prometheus, and so targets his brother, Epimetheus, instead. He has the gods fashion a beautiful gift—a woman, dressed in the finest clothes and jewelry, holding a forbidden box. Her name? Pandora. Epimetheus takes the gift, ignoring Prometheus’ warnings, and Pandora unwittingly releases evil and suffering onto the human race out of curiosity and intrigue into the contents of this forbidden box.

We live in the internet era, the latest development in the technological age. Just a few decades ago, the internet didn’t exist, and less than a century ago, neither did computers. This past year, computer science became the third most popular major at Dartmouth, just behind economics and government, with engineering sciences and biology following. Subjects such as classics, philosophy, English, and even history, that old staple of a liberal arts education, have dwindling numbers of students. Just over half a decade ago, in 2013, computer science wasn’t even in the top ten most popular majors. It’s unfortunate, as well as worrying, to see that only two out of the ten most popular majors are in the humanities. My peers are constantly bombarded with advice to “study something useful” and questions such as “what job are you going to get with that degree?” or, my favorite, “why would you study history? It’s all happened already. Stop wasting your time and learn something useful.” Of course, there are many reasons to study STEM besides parental pressure. We are entering a world of crippling student debt, rising housing prices, tremendous job insecurity, and a general uncertainty about the direction of the world. VUCA, short for volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity, has come to define post-Cold War society. We are untethered, floating into the unknown, and people are grasping onto the most reliable handles they can find. Many of my fellow students are racked with ever-increasing amounts of student debt every second they sit in a lecture, struggling to focus on the professor while worrying about getting their job applications in on time. In such dire times, why would anyone in their right mind study ancient Greek poetry? Perhaps all classics students are rich. After all, who wouldn’t want to wax poetic about the yonic nature of Minoan vases while rubbing shoulders with the urban elite attending the latest cocktail party at the Met? I digress. In my experience, at least, classics students are no wealthier than any of their STEM peers. Moreover, that’s not relevant to the topic at hand. In this article, I wish to make an urgent plea to my STEM colleagues to study the humanities, for their own as well as society’s benefit.

The Good: The Benefits of a Mixed Education

Studying the humanities gives anybody seeking employment a huge advantage. After all, it was the Greeks who initially realized that what you are is what you present to the world. Through the hours of revising resumes, drafting up cover letters, and stumbling through endless skype-interviews, one comes to realize the often-times brutal nature of group-living. The way you dress, the words you use, the people you’re involved with, and the qualifications you have on paper are all that anyone seems to care about. Success in the modern world requires people to be able to communicate clearly, efficiently, and effectively. Teamwork is the name of the game these days, and there are few good teams that can’t communicate. Studying the humanities teaches STEM majors to clearly articulate their ideas and findings as well as work together in teams to achieve their goals. No leader ever got far without being able to communicate their ideas with clarity and passion. Just look at the list of notable CEOs and politicians with liberal arts training: Stewart Butterfield, CEO of Slack, studied philosophy; Jack Ma, of Ali Baba, studied English; Susan Wojcicki, Youtube, studied history and literature; Brian Chesky, Airbnb, fine arts; Mitt Romney, politician and founder of Bain capital, English; Michael Eisner, former Disney CEO, English; Steve Ells, Chipotle co-CEO, Art History. To my CS-friends, Zuckerberg, who studied psychology before dropping out of Harvard, claimed that Facebook is “as much psychology and sociology as it is technology.” Steve Jobs echoed this idea, declaring that “technology alone is not enough… it’s technology married with liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields us the results that make our hearts sing.” A 2015 national survey of business and nonprofit leaders put out by the Association of American Colleges & Universities found that “nearly all employers (91 percent) agree that for career success, ‘a candidate’s demonstrated capacity to think critically, communicate clearly, and solve complex problems is more important than his or her undergraduate major.” These skills are taught in a liberal arts course, not most STEM courses (save the last skill). Additionally, 96% of employers agreed that college students should have experiences that teach them how to solve problems with people whose views are different from their own. There isn’t much debate in most math and science classes. Something is either correct or incorrect, or the sig figs are off. The humanities force students to deal with multiple plausible answers and people with valid, yet contrasting, beliefs.

The Bad: The Harms of a Narrow Education

Charles Proteus Steinmetz, known as the Wizard of Schenectady for his electrical engineering prowess, wrote that the rise of an engineering education, in lieu of a classical one, has created a third class of person in between the educated and uneducated, someone who is trained to do one thing very effectively but does not know much else. He writes that engineering courses are especially liable to “make the man one sided” by dealing exclusively with empirical evidence and its application. Engineers are perhaps led to forget, or not to realize at all, that there are other aspects of human thought and nature outside of hard evidence.

“But such learning of the engineering trade can hardly be called receiving an education, and certainly does not fit the man to intelligently perform his duties as citizen of the republic during the stormy times of industrial and social reorganization, which are before us….Education is not the learning of a trade or profession, but is the development of the intellect and the broadening of the mind, afforded by a general knowledge of all the subjects of interest to the human race, as required to enable a man to intelligently attack and solve problems in which no previous detail experience guides, and to decide the questions arising in his intellectual, social, and industrial life by impartially weighing the different factors and judge their relative importance.”

Though Steinmetz argued specifically in favor of the study of classical languages, literatures, and civilizations, these same lessons can be learned in other areas of the humanities as well. It is this broadening and stretching of the mind that perhaps makes the study of humanities so valuable to people like Steinmetz or any of number of CEOs in the world. Though engineering courses may teach you to solve the problems of today with the technologies of today, one must be able to solve the problems of tomorrow with the technologies of tomorrow just as well. No technical education can singlehandedly prepare anyone for that, even at the greatest institutions in the world. One must arm themselves with the tools of effective reasoning, open-mindedness, and bold caution in order to navigate the dark and hazy shores that lie ahead.

The Ugly

“I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” – J. Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer, head of the Manhattan Project, made this remark upon seeing the first successful test of the nuclear bomb. Only after he created the technology did he truly realize its harm. Once technology is created, and that “box” is opened, there is no turning back. Nuclear weapons technology has made leaps and bounds since then, and we now share with other countries an unprecedented ability to destroy the planet many times over. Even things less apparently sinister have dramatically changed our lives. The internet, for one, was invented as a way to make communicating between various computers that shared networks more efficient. Today, it has changed the face of human connection, forcing people to act as avatars with carefully monitored facades to meet new people. The rise of the dark web has made crimes such as human trafficking, sale of illegal substances and weapons, and identity theft ever more difficult to track down and prevent, not to mention the rampant waves of cyberbullying and ruining of lives through social media mob rule. Recently, it has also led to the spread of bigotry and extremism, inciting violence all over the world through the peddling of false information and ideological homogeneity of sources. I highly doubt that the inventors of the internet had this purpose in mind. Technology has the power to save lives and alleviate suffering for countless individuals—vaccines and medicines, protective gear for athletes and laborers, and safer buildings are just a few of the things we take for granted nowadays—but it is something with which we must proceed with caution.

We are quickly entering the age of artificial intelligence and biological engineering. Both of these fields are capable of challenging the very notion of what it means to be human. We are breaking new frontiers that have remained untouched for the entire existence of humanity, and we are doing so at a frightening pace. The speed of innovation has not been met with a commensurate consideration of all of the risks involved. AI continuously bests humans in seemingly everything. As we rely more and more on AI, we have to think carefully about what will happen when AI, armed with machines such as cars and drones and missiles, decides that, like in Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot, that humans are the greatest danger. In his novel, the robots are planned to protect the humans. They realize that the best way to protect humans from harm is to prevent them from doing anything. Should humans still pose a threat to themselves, the next logical step is to eliminate human beings (a dead person can’t be harmed). AI is far more effective than humans in strategizing and mobilizing resources. Will we be able to fight back against them if necessary? As Christian Lous Lange writes, “technology is a useful servant but a dangerous master.”

New breakthroughs in genetic technologies are opening the door to eugenics and human cloning, challenging age-old assumptions of the irreplaceability of individuality and the notion that all human life is precious and unique. These technologies largely rely on viruses that can infect the DNA and replace certain parts of a cell’s genome. We already know the horrors of chemical warfare and the capabilities of nuclear weapons. Imagine the damage that a biological weapon, targeted to mutate one’s DNA, could do to a population? I realize that I sound like a fear-mongering luddite. These questions, however unlikely and unrealistic, need to be asked before we reach a point of no return. Nuclear weapons began with research into new energy sources. Facebook, which has undoubtedly contributed to racial violence and genocide in Myanmar and social hostility in other places around the world, started out as a way to meet new people. Most of the time, we cannot empirically predict where new technologies will lead us to. Nobody could have predicted Facebook’s primary faciliatory role in the future genocide of tens of thousands of Rohingya in Myanmar, a primarily Buddhist country. Nevertheless, it is our duty to carefully consider these types of questions, no matter how farfetched they may seem.

Let’s return to the story listed at the beginning of this piece—it’s there for a reason. Pandora’s box of evils, once opened, can never recapture the malaises it released. Even for seemingly good things such as the eradication of genetic diseases, we cannot be naïve to the possible negative consequences. We must strive to align ourselves with the clever and wise Prometheus as opposed to his troublesomely ignorant brother, Epimetheus. The humanities teach us to be wise and prudent, to ask the important questions and think critically before it is too late, like Prometheus; and to be careful not to further the damage caused by his brother Epimetheus. Prometheus brings humans fire, blessings, and respite from their problems. Epimetheus, unthinking, careless, and recklessly desiring, doomed humans eternal suffering. We all must be careful not to overlook the negative consequences that inexorably follow beneficial technologies. Prometheus, in Greek, translates to forethought; Epimetheus, as you might expect by now, afterthought.

Be the first to comment on "Pandora’s Box"