One-hundred seventy-eight years ago, Anglo-American delegates from all over Texas met in the crudely hewn cottages of Washington-on-the-Brazos to wax prolifically about abuse they collectively suffered vis a vis the misgovernance of Mexico. These delegates were all settlers, mostly autodidacts and drunkards by night and farmers by day. Though most of the Texan Declaration of Independence is mired in classic 19th century pretension, the delegates strung this beauty of a sentence together:

We, therefore, the delegates with plenary powers of the people of Texas, in solemn convention assembled, appealing to a candid world for the necessities of our condition, do hereby resolve and declare, that our political connection with the Mexican nation has forever ended, and that the people of Texas do now constitute a free, Sovereign, and independent republic, and are fully invested with all the rights and attributes which properly belong to independent nations; and, conscious of the rectitude of our intentions, we fearlessly and confidently commit the issue to the decision of the Supreme arbiter of the destinies of nations.

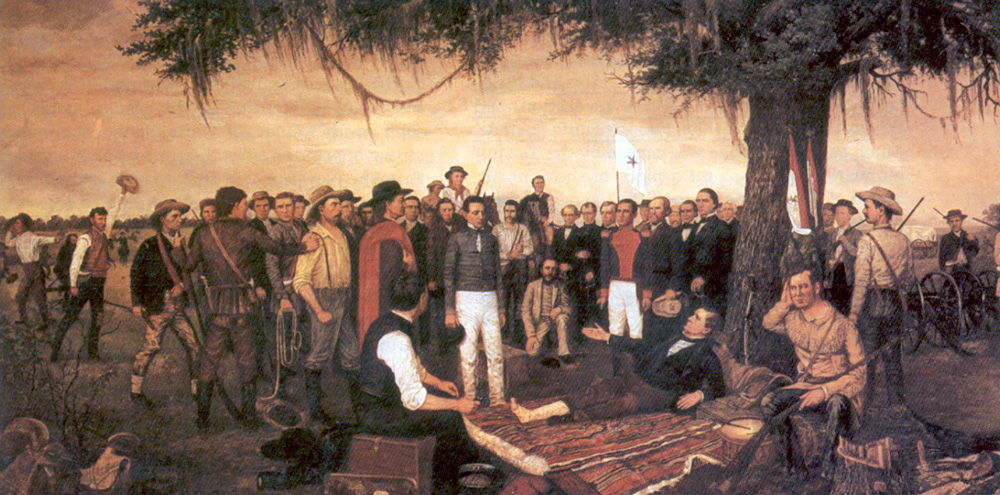

The ensuing war for independence was characteristically bloody and brief. “Texian” volunteers, as they called themselves, were men bereft of uniforms and discipline, and to win their independence they had to triumph over Santa Anna’s (called the “Napoleon of the West) professional Mexican army outfitted with cavalry, artillery, and ample supppy. Early on, the Texans lost two crushing defeats at the Alamo and the Goliad Campaign. At both of these conflicts, Mexican soldiers utterly annihilated the Texan forces, taking no prisoners. The ultimate battle of the war seemed to also be turning in the favor of Santa Anna. At San Jacinto, the final battle of the war, the first days of conflict were marked by Texan retreat. The Texan forces, lead by Sam Houston, however, risked their entire war on one daring surprise attack. Historians can’t decide whether the Mexican army was collectively drunken or asleep, but the final day of San Jacinto was devastating. The Texans completely overran the Mexican camp and slaughtered half of the army, taking Santa Anna prisoner. The Texans forced Santa Anna to sign the Treaty of Velasco, granting Texan sovereignty. Of the battle of San Jacinto, historian James Pohl said:

to also be turning in the favor of Santa Anna. At San Jacinto, the final battle of the war, the first days of conflict were marked by Texan retreat. The Texan forces, lead by Sam Houston, however, risked their entire war on one daring surprise attack. Historians can’t decide whether the Mexican army was collectively drunken or asleep, but the final day of San Jacinto was devastating. The Texans completely overran the Mexican camp and slaughtered half of the army, taking Santa Anna prisoner. The Texans forced Santa Anna to sign the Treaty of Velasco, granting Texan sovereignty. Of the battle of San Jacinto, historian James Pohl said:

Measured by its results, San Jacinto was one of the decisive battles of the world. The freedom of Texas from Mexico won here led to annexation and to the Mexican War, resulting in the acquisition by the United States of the states of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, California, Utah, and parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Kansas and Oklahoma. Almost one-third of the present area of the American nation, nearly a million square miles, changed sovereignty.

Mexico officially refused to recognize the newly christened Texan polity, which would later cause some issues during the Mexican-American war — with a couple of U.S. presidents and generals as well as some future Confederates among its list of notable alumni — but for all effective purposes Texas was its own country. With that, enjoy your Texas Independence Day. Celebrations can include, but are not limited to: tequila shots, square dancing, boot scooting, smokeless tobacco, tuberculosis, and secession. Remember the Alamo!

-Henry Woram ’17

Be the first to comment on "The Sometimes Immaculate Sometimes Drunken History of Texas"