Editor’s Note: Indian classical music is one of the world’s oldest and most systematically developed genres of music. However, many Westerners are, unfortunately, unfamiliar with it aside from certain pop culture elements, such as the iconic sitar and/or the great sitarist named Ravi Shankar, who was embraced warmly by Western audiences in the 1960’s. On October 24, two Indian classical musicians from the Indian city of Banaras, considered Hinduism’s cultural and religious capital, came to the College to give a performance of Indian classical music. The performance, hosted at Rollins Chapel, was well attended by students, faculty, and community members of all backgrounds, including some from outside the immediate Upper Valley area.

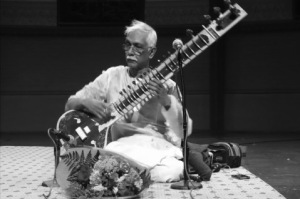

Mr. Rabindra Goswami, a professional musician for nearly five decades, performed traditional raga music on the sitar, an Indian stringed instrument. As was first detailed in a campus-wide email announcement, Mr. Goswami is a disciple of the late Amiya Devi, and has studied the ancient Dhrupad style of music under Pandit Ramakant Mishra. He also studied under Dr. Balchandra Patekar of Banaras and Mumbai to master raga’s advanced intricacies. He has won a number of competitions and awards in India for his musical talents – such as first place in the 1967 Prayag Sangeet Samiti All-India Competition – and has performed in person across India and abroad as well as on Indian television and radio. He is currently a Fellow at Yale University’s Institute of Sacred Music.

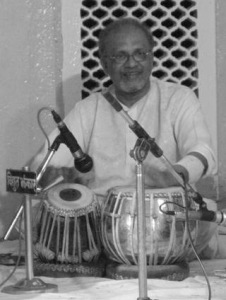

Mr. Ramu Pandit (right) playing the tabla and Mr. Rabindra Goswami (left) playing the sitar at a prior performance. Both musicians are renowned masters of north Indian classical music.

Mr. Ramu Pandit, a long-time professional performer of Indian classical, semi-classical, and folk music, performed raga music on the tabla, an Indian instrument consisting of two drums that are played by the hands. As was also first detailed in a campus-wide email announcement, Mr. Pandit is an educator with a seasoned specialty in explaining the concepts, traditions, and history of Indian music to western audiences. He has also performed in person across India and abroad and on India’s equivalent of National Public Radio (NPR): the All India Radio. He also helped play music for Indian film soundtracks for the famous composer S.D. Burman in Mumbai. He currently directs the Sarangi Institution of Banaras – an organization he founded to preserve the sarangi, an Indian classical instrument which now has few masters – and for thirty years was the coordinator of the University of Wisconsin’s College Year in India Program.

After their stellar performance, both great giants of Indian classical music sat down with The Dartmouth Review to answer some questions and express their thoughts.

The Dartmouth Review (TDR): How were you both introduced to Indian classical music?

Rabindra Goswami (RG): I grew up in a home in which my aunt played the sitar … my uncle played the tabla, and my other uncle sang. I was brought up in a musical atmosphere, and that’s how I got started.

Ramu Pandit (RP): I loved music from the beginning. I started with learning vocal music in school. After I was eleven, I started learning tabla… I was lucky enough to study music under Sharda Sahai Ji [“Ji” is a suffix of respect in many Indian languages, akin to referring to someone as Mister or Miss], my guru, whose forefathers invented the Banarasi style of tabla.

TDR: The Raga, the central aspect of Indian Musical Theory, is an incredibly deep, complex, and brilliant structure. For our readers who have no background, though, how would you present the concept of the raga in a simple way?

RP: We use the magical power of music in raga to affect the heart directly. I have met people who have never heard Indian classical music, but as soon as they hear it, the effect is so strong on them that you can see the tears on their face and … their goose bumps … Nobody is singing; there are no words. But the effect of just the notes are so strong that it makes you think. That is raga.

RG: Well, to appreciate music you don’t always have to be so knowledgeable about it! … The harmony, the melodic structure: it all creates a musical atmosphere… The raga is true when it touches your heart and affects your soul. That is the raga. If it does not – if it does not color your mind – it is not true raga.

TDR: How do you feel that Indian classical music relates to Indian history and culture?

RP: A lot of political changes have taken place throughout the past few centuries in India. Whoever has come here [to India] has realized the power of Indian classical music… especially the Sufis [an Islamic sect noted for its liberality and musical contributions]. They brought their own music to India, but they found the power of Indian classical music so immense … that they learned and contributed to it too. There was actually an era in the Mughal regime when this music was ordered to be abandoned by hardcore Muslims … Many musicians sacrificed their religion and converted to Sufi Islam or Hinduism from hardcore Islam just to preserve this music. To save this music, because it is beautiful, they converted.

RG: Through time, music has travelled between all countries… Every country’s music has their influence on other countries’ music… Even now, people from all over come to India to… learn something that Indian music can offer them, and they mix it up with other types of music. It’s kind of an exchange that’s going on. Like I have come to America and am learning the sacred music of the churches… So I can preserve and add to raga on my own. So there’s always an exchange.

TDR: Those wishing to study western classical music can study at well-established music colleges and universities. Many prestigious Indian universities also offer degrees in Indian Classical Music today. How are students of Indian Classical Music trained according to tradition?

RP: All over India, there are schools and colleges who offer courses in Indian classic music, with degrees and everything… The Government of India also offers scholarships for those wishing to learn… and teach Indian classical music. My own brother taught the tabla in Russia for a bit. But for the real essence, if you want to learn the real thing, you have to go to a master, or a guru … and then you become his disciple, not student – there’s a big difference there. It’s a one-to-one relationship, like father-to-son. That’s the real way to learn Indian classical music …

RG: Also, this isn’t just learning the music and its musical notation. After someone learns these basics, he has to transform it into the emotions of the raga. The main thing of the music is how you can present it emotionally … To learn that requires a real relationship with a guru, not just music courses.

TDR: When a lot of people in the West think of Indian classical music, think of this very spiritual quality to it, and they don’t say that about rock-n-roll or Bollywood today. Why would you say that Indian classical music is special in this spiritual sense?

RG: Indian classical music is not like entertainment music … Its main purpose is for an enlightenment of sorts through music. We call it Sadhana [spiritual meditation/devotion]. You go on and on, playing and practicing until you … reach a higher, greater level.

RP: Like I said … it’s a spiritual journey and experience. … Through this journey and experience, you can sometimes also amuse your audience, but that is not the goal … The music is so powerful, even normal yoga and therapy classes use Indian classical music because its immense power creates a certain concentration.

TDR: Indian Classical Music has a long and rich history of great composers, musicians, and musicologists. How do you feel you are contributing to this rich musical tradition?”

RP: We are just passing on this tradition. What happens is that you unknowingly contribute to it… It’s like the ocean. We can dive in and find a pearl, but that pearl was always in and from this great ocean. To say we created this pearl is not right. [Indian classical music] is an ancient continuity of sages and gurus and disciples who have continually added to this tradition … We try to just add more to it and spread it. To say that, “Oh, we contributed this and this to the tradition,” is not correct.

RG: Even when we play the same ragas, there is always something new added to it. It’s never the same rendition. Every time we play one raga, it’s a new improvisation, and something new is added and changed. In this way, we are always unknowingly contributing to it.

I am a music teacher and tought Indian classical Vocal ( Uttar hindustani) I wish to teach music. If You can help me. I am living in White River Junction