In 1910, Dartmouth Outing Club president Fred Harris ’11 devised a celebration of winter sports, and he invited students from nearby colleges to compete against the unbeatable Dartmouth skiers. Officially named Winter Carnival the following year, the annual event evolved into a legendary festival, a favorite social weekend for Dartmouth undergraduates and for students from other schools.

In the Beginning

In 1910, skiing had not yet emerged as a common form of winter recreation. At Dartmouth, Fred Harris ’11 and his friend A.T. Cobb ’12 were among the few students who participated in the sport. Harris, as president of the newly formed Dartmouth Outing Club, had an interest in promoting skiing and winter sports, so he undertook the organization of a weekend devoted to those activities. Harris wrote a letter to The Daily Dartmouth outlining his proposal to Dartmouth’s community. Shortly thereafter, the newspaper published an editorial calling for an event that could act as the “culmination of the season.” The weekend, read the editorial, would “undoubtedly be a feature of College activity which from its novelty alone, if for no other reason, would prove attractive. It is not impossible that Dartmouth, in initiating this movement, is setting an example that will later find devotees among other New England and northern colleges.”

The initial “field day” proved to be a huge success, popular with students, faculty, and local townspeople. The events of the first weekend, in which students from other schools participated, included ski racing, ski jumping, and snowshoe racing. Harris was a hands-down favorite to sweep the events, but a knee injury sustained during practice—coupled with the distraction of a fire in his dormitory, South Fayerweather Hall—detracted from his performance. Cobb emerged victorious in every skiing event.

Encouraged by the popularity of the winter sports weekend, students began to lay out plans for the first Winter Carnival in 1911. Such an event, they reasoned, would benefit from a female presence. Said The Daily Dartmouth: “It is up to every man with a purse or a heart, or with a bit of enthusiasm for a good time when it heaves in sight, to make haste to procure that most necessary item.” Dartmouth students heeded the advice, and the first band of Winter Carnival dates consisted of fifty visitors from Smith, Mount Holyoke, Wellesley, and other nearby women’s colleges. A 1939 Winter Carnival article blasted: “Hanover is set back on its collective heels as girls, girls, girls pour in.”

The new social aspect of the weekend, which consisted of a dance and some theater, was welcomed by all involved, but athletics remained paramount in the celebration. Once again, Harris and Cobb dominated the events, with the latter retaining most of the crowns won the previous year. The ski jump was the biggest thrill for many spectators, who had never seen or experienced such a thing.

The Outing Club Ball, which followed the sporting events, signaled that the weekend was more than a field day. For Dartmouth students, Winter Carnival became an instant tradition. “The Winter Carnival of the Outing Club won a deserved success, and will undoubtedly remain a permanent feature of Hanover winter life,” wrote The Daily Dartmouth. “This is how it should be. Winter is the characteristic Hanover season, winter weather is Hanover’s finest weather, and winter sports should be, and are coming to be, the characteristic sports of the Dartmouth undergraduate.”

Image courtesy of Rauner Special Collections

The Legend Grows

Before long, the Dartmouth Winter Carnival developed into the most celebrated college weekend in the nation. In 1919, National Geographic devoted a feature article to the “Mardi Gras of the North.” The number of activities increased, coming to feature such eclectic events as “skijoring,” and so did the number of visitors to Hanover. Dances held by Dartmouth fraternities became a highlight of the weekend—which, of course, required a significant number of female guests. Trains would make their way north from New York and Boston, making stops at Northampton, Springfield, Holyoke, and Greenfield to pick up female passengers on their way to White River Junction, where expectant Dartmouth men would greet them with cheers of jubilee.

The scenario is singularly detailed in the film Winter Carnival, a fictional account of the 1939 celebration. The storyline follows the somewhat corny romance between a Dartmouth professor and his old flame, a divorced duchess who had held the crown of Winter Carnival Queen in her younger days. Among the amusing subplots is a situation at the campus daily, where the incoming editor decides to change the paper to a tabloid called the Dartmouth Graphic. Its headline: “Smooth Babes Invade Campus.” An entertaining look at Winter Carnivals of old, the movie shows not only students meeting their dates at the train station but also footage of athletic events and black-tie dances at fraternities.

Winter Carnival’s producer, Walter Wanger ’15, enlisted Budd Schulberg ’36 and author F. Scott Fitzgerald to write the screenplay. When the duo arrived in Hanover to write the story, Fitzgerald drank so heavily that he was fired from the project. Despite Fitzgerald’s absence, the film’s storyline perhaps shows a bit of his influence: at the black-tie fraternity dance, the dejected college professor drowns his sorrows in double scotches. Winter Carnival was named “one of the five objectionable pictures of 1939” by the Catholic Legion of Decency, a distinction shared by Gone With the Wind and Of Human Bondage. It’s a must-see for every Dartmouth student.

Image courtesy of Rauner Special Collections

All Hail the Queen

One tradition that emerged fairly early in Carnival history was the crowning of the Winter Carnival Queen. The tradition, possibly, was inevitable, since a highlight of Winter Carnival was of course the presence of women on the normally all-male campus. Remarked one former president of the Dartmouth Outing Club, “Dartmouth likes lots of company over Carnival weekend, especially if it is cute and wears skirts.”

The tradition of the Winter Carnival Queen began in 1923, when the young Mary Warren was honored and adorned in garb from the Russian Royal Court. The criteria for Carnival Queen were changed in 1928 so that the Queen would be selected in line with the Carnival’s outdoor theme. The editors of The Daily Dartmouth encouraged the choice of “the most charming girl in winter sports costume for the Queen of Snows.”

The competition for the title of Winter Carnival Queen continued for forty-nine years until, in 1973, the Carnival Committee decided to eliminate the tradition. Said George Ritcheske, the committee chairman, “Prevailing attitudes indicate that contests which stress beauty as their primary or only criterion no longer have the widespread popularity they once enjoyed.”

Image courtesy of Rauner Special Collections

The Heart of the Carnival

When Fred Harris first conceived of a weekend winter celebration, the goal was to encourage participation in winter sports. At the first Winter Carnival, skiing was still a fledgling sport, and few competitors could be found to participate. Today, in tandem with the growing popularity of the sports, the Carnival events have been updated. In 1910 skiers raced in the “100-yard dash.” Today they race in the giant slalom.

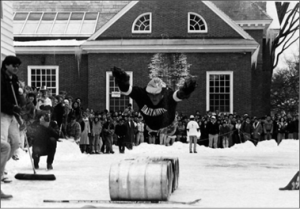

Other events, such as the once-popular snowshoe races, were replaced. Psi Upsilon’s keg-jumping contest was for almost two decades one of the weekend’s more lively events, before it was canceled for insurance and liability reasons. The “Polar Bear Swim” at Occom Pond has also become a mainstay. Since the Carnival’s inception, sporting events have remained at the heart of the weekend, although many students now focus more on the parties.

Image courtesy of Rauner Special Collections

Changing Traditions

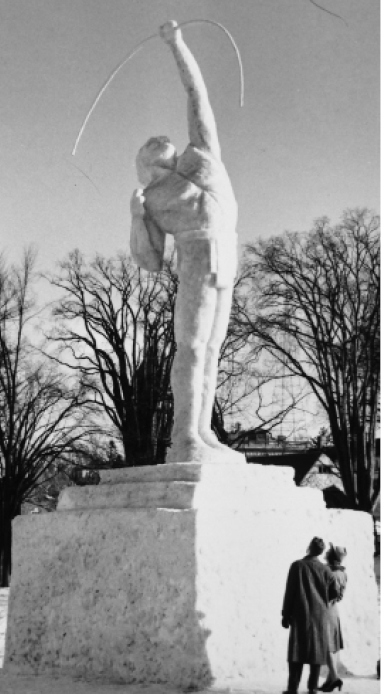

In 1939, a thirty-seven-foot snow statue of Eleazar Wheelock “toasted visitors with a fifteen gallon mug.” Visitors to Dartmouth will appear again this year for Winter Carnival, but they won’t be regarded as the saviors of the social scene, as they once were. Dormitories, surely, are no longer vacated to make room for trainloads of female guests. Nor is the Hanover Inn cleared out and turned into a women’s residence. Today, because of increased College oversight of the fraternities and sororities, much of Dartmouth’s past hospitality is no longer possible, and visitors are regularly turned away.

Image courtesy of Rauner Special Collections

Image courtesy of Rauner Special Collections

In 1998, the Carnival turned ugly. In the wake of President Wright’s and the trustees’ first salvo against the Greek system with the announcement of the Student Life Initiative, the Co-ed, Fraternity, and Sorority Council canceled all Carnival celebrations. “I haven’t been invited to many fraternity parties this weekend,” President Wright announced at the opening ceremonies, “but I still plan on having a good time.” Students booed Wright and the next day held a rally at Psi Upsilon fraternity. “President Wright’s announcement on Wednesday embodies how not to run a college,” said Psi U president Teddy Rice. “This cannot be over. And if it is, then I’m going to go down fighting.”

Recent years’ debates over Dartmouth’s community life have found less proactive, and more litigious, expression. Traditions like the Psi U keg jump have been shut down, and their return seems unlikely as the regulations that govern student life grow stricter every year. “There was nothing like it almost anywhere,” Budd Schulberg told the New York Times of Winter Carnival in its earlier years. “There was a sexual revolution going on. And for the girls—as we called them then—it was a big honor to be invited. There was enormous excitement in the air. It was romantic, really, in an old-fashioned sense. It’s still what you’d call a party, but it’s nothing like it was back then.”

Image courtesy of Rauner Special Collections

Image courtesy of Rauner Special Collections

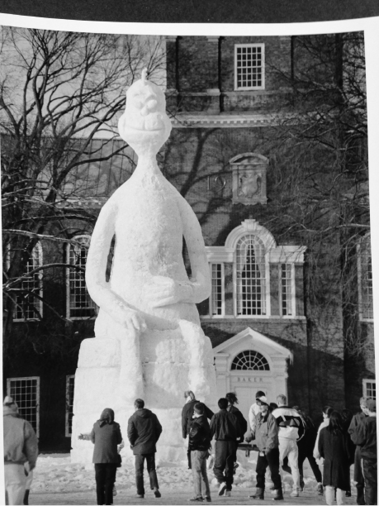

Several years ago, Dartmouth suffered the clumsiness of a Carnival Committee that, after choosing Calvin and Hobbes as the Carnival’s mascots, insisted that an alternative theme be chosen—despite the comic’s author’s insistence that the use of “Calvin and Hobbes” was okay. The committee eventually settled upon some hybrid that left the student body scratching its collective head. Then came the snow sculpture, both sad and small in comparison to its ancestors.

The fate of unimpressive sculptures has seemed to be omnipresent in recent years. While no one can be held responsible for the lack of snow that has led to smaller sculptures constructed out of imported and purchased snow, it nonetheless leaves a gaping hole in the Dartmouth experience for those current generations of Dartmouth students who have yet to witness the spectacular works that once marked this event.

Though the Carnival is not what it once was—and what is these days?—students this year will again reclaim College traditions and hark back to the days of old. Winter Carnival remains a celebration of the outdoors, of life, and of Dartmouth.

This set piece to The Review’s Winter Carnival coverage was written by Emily Esfahani-Smith. It has been reedited.