Editor’s note: On September 29, 2023, Editor-in-Chief Matthew O. Skrod (TDR) interviewed Robert Gitt ’63 (RG), a film preservationist and historian. After graduating from Dartmouth, Mr. Gitt remained at the College for seven years, programming films at the Hopkins Center under the auspices of Dartmouth College Films and the Dartmouth Film Society. From 1970, he worked in Washington, D.C., as the American Film Institute’s preservationist. In 1977, Mr. Gitt began his long and celebrated career as Preservation Officer of the UCLA Film & Television Archive. In that capacity, he effectively created the Archive’s preservation program, pioneered techniques of film preservation and restoration, and won world renown for the Archive through the excellence of the craft performed under his direction.

Until his official retirement in 2006, Mr. Gitt personally conducted or supervised the preservation and restoration of more than 360 feature films and hundreds of short subjects. Since that time, Mr. Gitt has remained substantially involved in film restoration and preservation efforts, perhaps most publicly by leading a 2½-year restoration of Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes (1948), a project that received its premiere at Cannes in 2009. Mr. Gitt has received awards from the British Film Institute, Le Giornate del cinema muto, FOCAL International, and the Association of Moving Image Archivists.

TDR: Mr. Gitt, thank you very much for taking the time to speak with The Review.

RG: I’m glad to do it.

TDR: Would you be able to talk about your undergraduate years at Dartmouth and your early involvement with film?

RG: I got to know the director of Dartmouth College Films, J. Blair Watson, very well, and of course I went on to work for him for several years. I liked Blair a lot, as did my older brother, who also went to Dartmouth. He was ten years older than I was and attended from ’49 to ’53. He knew Blair and was very active in the Film Society. So, when I got to Dartmouth, I immediately looked up Blair Watson and the Film Society.

Strangely enough, though, for the four years I was a student at Dartmouth, the main thing I did was work for WDCR, the student-run radio station. I was a member of the Film Society and went to see a lot of the films, but I was most active in radio.

I got reasonably good grades in my first two years. The third year, I made a mistake. I had to major in something. My roommate was a Government major, and I had just taken a Government course on the history of the Supreme Court, which I had liked a lot. So, I decided to major in Government. But it turned out that I didn’t like the major at all. I was bored, and my grades were often poor.

When I graduated in 1963, I wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do. Because I was in the Film Society and knew Blair, I learned he was looking for somebody to work for him. That’s how I started with him at Dartmouth College Films. I began looking at films, projecting films, getting equipment, and so on. And in 1965, I became the program manager of the Dartmouth Film Society.

After my brother graduated from Dartmouth and served in the Army during the Korean War, he began collecting films on the basis of having talked with Blair and seen a lot of films through the Film Society. He started a very good film collection in 16mm. For me, while I was working for Blair, I also became a film collector of 16mm prints and 35mm prints. I developed quite a large collection of 150 titles, including many of the finest films ever made: Hitchcock films, Citizen Kane, and so on. They were beautiful prints.

TDR: I imagine J. Blair Watson and members of the Film Society were aware of Dartmouth’s historical connections to the film industry? Did any of those important figures make appearances on campus?

RG: Yes, we knew there were a number of alumni who were famous producers, like Walter Wanger and Arthur Hornblow, Jr. There was also the fine actor Robert Ryan.

Blair and I had dinner with Hornblow one time when he was visiting campus. It was late in his career, and I remember he was very nice—a good person to talk to. Robert Ryan was on campus several times as well, and he was a very bright person and good to talk to. During a visit to campus, Robert Ryan appeared at the Film Society’s screening of Renoir’s The Woman on the Beach, and he introduced the film.

In the thirties, of course, Walter Wanger was angling to get an honorary degree. And that’s why in 1939 he made this horrible movie called Winter Carnival. We had a print of it and used to laugh at many of the scenes. By the ’60s, Wanger still lectured at Dartmouth from time to time and took himself very seriously. These were talks about the complicated future of communications and how this would affect society.

Another important figure was the director Joseph Losey. When I was program manager of the Film Society, I put together a series of his whole career basically. And the following year, in the winter of 1970, he actually agreed to come to Dartmouth to teach, and I was his assistant. I would get films for him to show in classes. Some people thought he was a difficult person, but I got along with him well.

In his course, Losey would talk about filmmaking and film producing and so on, and some of his students made trial films. By that point, Losey had made some very good pictures like The Servant and Accident, and he was about to make The Go-Between. He was an excellent director. However, he had his likes and dislikes. It just so happened that, while he was at Dartmouth to teach, we were having a Howard Hawks festival at the Film Society, and he hated Howard Hawks with a passion. He couldn’t stand Howard Hawks.

Howard Hawks was very conservative, I guess, and Losey was very liberal. Losey called me on the telephone one time and asked what we were showing at the Film Society that week. I said, “Well, we have Bringing Up Baby by Howard Hawks.” Sighing, he replied, “If that’s the best that Mr. Hawks can do, I shall have to remain unimpressed with his work.” So, he wasn’t very nice about Howard Hawks. Personally, I do like Howard Hawks.

Blair and I also both worked with Maury Rapf, whom I knew very well. I knew Budd Schulberg slightly—he was only occasionally at Dartmouth. Rapf had been there on and off for years. When he had been blacklisted in Hollywood in the ’50s, Dartmouth gave him a job. So, my brother knew him. In the ’60s, I saw him all the time, often with Arthur L. Mayer [a visiting professor of film and a well-known film distributor and exhibitor -Ed.].

Incidentally, I knew J.D. Salinger very well, as did the entire Film Department. He came to our office all the time to borrow prints, and we borrowed some films that he had. He was also a film collector. He collected Laurel and Hardy, and Alfred Hitchcock, and various other things in 16mm. He was always very friendly and smiled. And he and I talked, and I actually got him some prints from my dealer in New York City. So, I knew J.D. Salinger for quite a while. I also knew his son when he was just a boy. I’m always surprised when people say they know nothing about Salinger and that he hid away for much of his life. He lived near Dartmouth, so I guess that meant hiding away to much of the public!

TDR: In October 1965, Dartmouth played host to a three-day conference on the study of film in a liberal arts education. What memories do you have of this conference?

RG: Yes, that’s right. It led to the founding of the American Film Institute. I went to all the meetings during the conference.

Blair was heavily involved in the conference. George Stevens, Jr., was also very much involved, and he was later the first head of the American Film Institute. David Stewart, from Washington, D.C., was in charge of the conference and organized it all.

I remember that Pauline Kael, the critic, was present too. She came to Dartmouth three or four times in total while I was there.

Wanger and Hornblow were also present at the conference. So was David Picker, a Dartmouth graduate and the head of United Artists. Dore Schary was there too. He was not a Dartmouth graduate but had become the head of M-G-M when Louis B. Mayer was forced out in the early ’50s.

During the conference, we had a screening for the attendees in which I was involved: the Rouben Mamoulian film Love Me Tonight, which is a very entertaining early-’30s musical. They liked it a lot. We also ran some funny previews and so on. It was a Friday night, I remember, and I was the projectionist.

TDR: In the late 1930s, Wanger established at Dartmouth the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Script Collection. Did you know of this collection while at the College?

RG: Yes, I remember it. I looked at some of those scripts, and I remember the collection very clearly in the library. What’s sad about it is that they used to have an original script of Citizen Kane. I don’t know who it originally belonged to. Somebody stole it, unfortunately, so they had to become a little more careful after having previously made all the scripts easily available.

TDR: While you were at Dartmouth, were courses still making use of the script collection?

RG: I don’t think so. When I went to college, there weren’t any film courses at all—pretty much anywhere. But I was very interested in film as a hobby. As the years progressed, people did start having serious discussions, and, in fact, as a result of that conference in 1965, people began teaching film on college campuses. And that was more or less the start of everything. Before that, there were only a few schools that offered film courses, like UCLA.

But in the 1960s, college students were very enthused and interested in film as a whole because of all the good new films that were coming out of France, Sweden, and Japan and so forth. But they were also interested in seeing some of the great films of the past. And we used to get very good attendance at the Dartmouth Film Society.

That’s one thing I’m sorry about today. I suspect that, in recent years, there’s still been some interest, but there hasn’t been nearly as much as there was. I was lucky to be at Dartmouth when so many people were appreciating film in the 1960s.

The Dartmouth Film Society once was a great presence. We had some very nice programs. I remember, I programmed a tribute to Jean Renoir and a tribute to Joseph Losey. We also did Howard Hawks, as I mentioned, and John Huston. The producers from Dartmouth [referring to Wanger and Hornblow -Ed.] had retrospectives as well. We showed almost all of the films that these people made, and audiences appreciated it.

TDR: You had mentioned that the 1965 conference led to the creation of the American Film Institute. May I ask how you decided to go to the AFI, and when you decided that you wanted to work in preservation and restoration? Did you make that decision at Dartmouth, perhaps born of your interest in collecting films?

RG: I was collecting films while I was working at Dartmouth, and sometimes I would get two prints and then put the best parts of each together into one good print.

When the Film Society ran Olympia, Riefenstahl’s film of the 1936 Olympic games, I obtained a 16mm print from a film collector whom I knew very well, David Shepard. His print was of the whole film, and he’d gotten it from Riefenstahl.

But the 35mm print that was sent to us by the Museum of Modern Art was all out of order. Somebody had apparently taken all of the best parts of part II and put them into part I, and then the leafings were all in part II.

So anyway, I completely changed the order around, and when we sent it back to MOMA, it was all in order again, based upon David Shepard’s 16mm print. The people at MOMA were horrified and called me up, and I explained what had happened. And they said, well, don’t ever let it happen again, but thank you. Anyway, I got through that one alright.

So, I became interested, in that sense, in restoring and putting films back together properly—even while I was at Dartmouth.

When the American Film Institute was formed, David Shepard was on the staff of the archives. As I mentioned, I knew him because he used to show films for the Film Society, and he invited me to come down to D.C. and apply for a job. I did, and I got the job, and what I was supposed to do was work in the archives, but they had a budgetary problem.

So, for the first two years, I was booking prints for the theater and was in charge of theater projections and so on, and that was okay. But I really started restoring and preserving films the third year that I was at the AFI, when I began working on Lost Horizon, the Frank Capra film from 1937, which had been reissued during World War II in a greatly truncated version.

It was only 90-something minutes long rather than 132 minutes. So, I started working on that, and it was my first important restoration project. I was at the AFI for almost five years.

My film collection, as I mentioned, had a lot of very good titles in 16mm and 35mm, silent and sounds, Keaton and Chaplin. By the time I was getting heavily involved in archival work at the AFI, I had a very big collection of films. A man at the AFI named Larry Karr, who passed away some years ago now, told me that he also collected films. And once he joined an archive, he said, he began realizing that his instinct to collect films was for an important reason—to keep them for the entire country. I started to agree with his perspective.

TDR: Could you discuss your decision to move to California and work for the UCLA Film & Television Archive?

RG: I had done some work at the AFI’s west-coast office in the summertime, and I’d really liked the California weather and Los Angeles. I also knew I wanted to work at UCLA.

But when I moved to California, I actually first worked with Ralph Sargent at his laboratory, and I got some more experience. I printed films and so forth for a while too. And then, in the middle of 1977, UCLA had an opening, and I went to work there.

The Archive had not yet been doing much preservation or restoration, but it had large collections of films. These came from the Paramount Library after it was sold to Universal, which hadn’t wanted to deal with all of Paramount’s old nitrate prints. As time went on, Warner Bros. put all of its nitrate prints in the Archive too.

So, it was starting to become a big thing, although it was already there and operating. But it wasn’t really doing film copying, photographic work, or restoration work to any great degree before I got there.

TDR: As I understand it, then, the practice of film preservation or restoration was still in its infancy at that point in time?

RG: Yes, it was still in its infancy, and the truth is that a lot of what archives were doing at that time was very bad. The laboratory work was poor.

They tried to make modern, safety copies of old films from the ’20s or the ’30s, which were on flammable nitrate film stock and which also deteriorated. They went to outside commercial laboratories, which were set up to work with new black-and-white film, not old film. And so these laboratories couldn’t handle shrunken film. What happened was the film would vibrate as it was being printed, yielding a very fuzzy result. As a result, most of the archival work being done in the ’50s and ’60s wasn’t very good. They hadn’t yet learned what was necessary to do to deal with shrunken film.

TDR: How would you distinguish preservation from restoration? I should think that, in the modern sense, restoration likely refers in part to work done digitally?

RG: Oh yes, and I might add that digital is wonderful. I wish that we’d had digital forty or fifty years ago. It really is amazing, in terms of removing scratches and dirt. Even though I’m retired now, I do work occasionally on little projects, and I’m currently working with a woman who knows a good deal about it.

But I wish I had it years ago. Some of the restorations that I did back in the day still hold up well and look good. But some of them were scratched badly, and we couldn’t do anything about it. Today, people can.

As to your question about terminology, older films are on nitrate stock, which is very unstable and also very easily catches fire and deteriorates. The main thing that most of the archives in the late ’50s and early ’60s were doing was trying to raise money to make modern safety copies. And as I said they had problems with shrinkage. What the archives were doing was preservation. They’d try to make a good copy of something, with the right contrast, that would serve for the future.

Restoration works somewhat differently. Restoration might be necessary if there was censorship, or if a film is very old. You might have to obtain several prints from different countries and put them together to make one complete print. This is often true of films from the silent era. But even during the talking era, in the case of reissues, the studios would ruin films by cutting them shorter. So, by checking with different archives throughout the world, I and other people doing restoration could put together prints that were the true, full length of the film, the way it was originally exhibited.

You always want these reassembled, full prints to look as good as possible. Some of my projects included restoring early color films, like The Toll of the Sea from 1922, in two-color technicolor, which is red and green. I also had three-strip technicolor projects, like Becky Sharp from 1935, which was the first time all of the colors could be photographed naturally. I worked very hard on that project with Richard Dayton of YCM Lab. And we involved the director, Rouben Mamoulian, who was supportive of our efforts.

It was good to know Mamoulian. He was a great director, both on stage and on film. It’s strange because he had a wonderful career for quite a while, but it dropped off. He directed Oklahoma! and Carousel for Rodgers and Hammerstein on Broadway, but after that he had all kinds of trouble and didn’t do too much more. I don’t know what happened. But he was very nice to us, and helpful, when we worked on Becky Sharp. And that’s an example of a restoration because some of the colors had to be restored. The negatives were stored in New York, and some of them were stored in Los Angeles. The film had been re-released as a two-color picture in the World War II era, and that version looked terrible. We restored the full color as best we could in all the reels of the film.

TDR: On the subject of Mamoulian, to what extent were you able to involve films’ directors in your restoration projects?

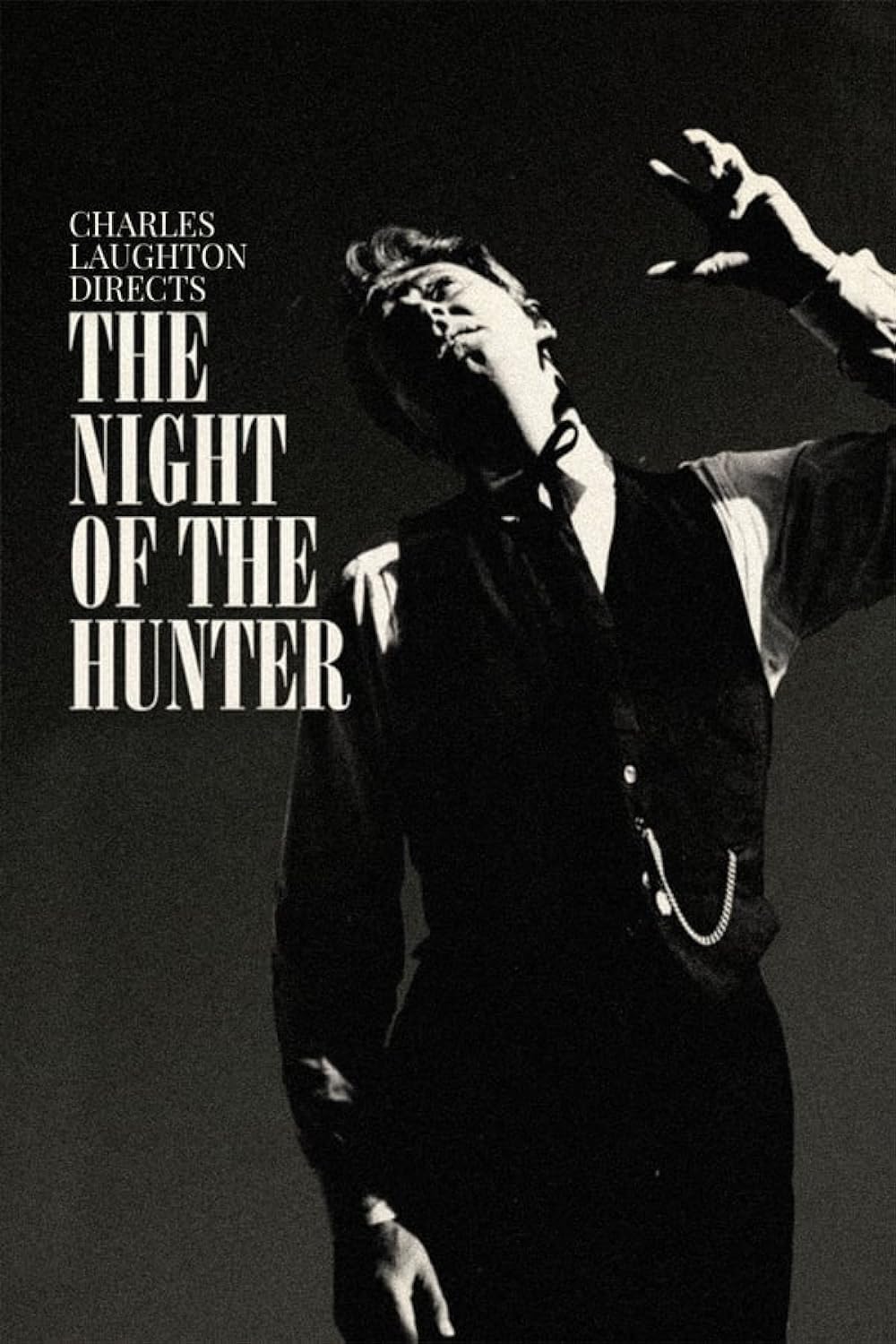

RG: Well, because I worked on many films that were old even at the time, having been made in the ’20s and ’30s, a lot of the people had died or were no longer available. But Mamoulian did help us out on Becky Sharp. Howard Hawks was very, very old and then died. In the case of The Night of the Hunter, I’m quite proud of the work I did on that film and its rushes, but of course, Charles Laughton had died in 1962. So, often the people were no longer around.

However, some people were. For instance, there was Budd Boetticher, predominately a B-movie director, who had made very fine films. I worked on a couple of his films, and he gave advice and helped out. I got to know him, and he was very nice.

Having directors sitting there, seeing our restoration, and saying, “Yes, that looks good,” was helpful. Sometimes they would also have anecdotes and details about missing scenes.

in Santa Clarita | Courtesy of Ron Kraus

TDR: How would UCLA go about choosing projects? Was this a UCLA decision, or did the Archive respond to interest from the studios? Would UCLA independently restore films?

RG: We had good friends at all the studios, and we would talk with them about their own, in-house programs. When I first started doing restorations, the studios were not taking care of their old films at all. Later, they gradually began restoring films, realizing that there was a home media market for them. So, they began taking better care of their films, and today they’re taking very good care of them.

But occasionally we would talk with the studios and make decisions. If we had films in our collection that were of interest to the studios, we would restore them. And in some cases, we had better prints than the studios did, because some of the copies they possessed were not very good, while our prints were originals.

Of course, we didn’t always get “permission” to work on projects. We were an archive, and our attitude was that we were doing something to make films stay alive. We were doing something that was favorable to the studios.

Like all archives, we were always looking for money and short of money. I’m happy to say that David Packard loves film and supported a lot of our projects. I still know him and actually work part time at the Packard Humanities Institute at the moment. He was very helpful.

But as I say, all archives have struggled for money. We would try to copy things before they deteriorated or went bad, but sometimes we weren’t able to do so. We tried to do the most important films, of course, but sometimes we lost some very interesting B pictures and so on, and it made us feel bad that we didn’t have the money. The word used is “junk”—we had to junk, or throw away, old nitrate prints when they started getting oozy, powdery, or smelling awful.

We’d save what we could of them. Maybe reel three was turning to ooze, but reels one, two, four, and five were okay; we’d keep those reels but throw reel three away. We had to do that, unfortunately. Today, it is fortunate that nitrate films are stored in very cold conditions, and based on what people have learned, a lot of them will actually last a lot longer than we once thought. We used to store our nitrate film in uncooled vaults. We didn’t know any better. We did the best we could, but that’s the way it was.

Something I should mention, and I’m a little worried about this today, is that nobody knows in the long run just how long digital copies will last. A lot of research is being done into this at the moment. People are trying to determine in what format a film that has been restored can last for hundreds of years. We don’t want them to suddenly get erased or go bad. These days, a lot of restorations are just being stored digitally, although some are then transferred back to film.

TDR: You mentioned earlier Becky Sharp and The Night of the Hunter. You famously acquired the rushes for the latter film, culminating in your documentary, “Charles Laughton Directs The Night of the Hunter.” Could you discuss the background to that enterprise? Also, do you have any other favorite or especially memorable restoration projects that you completed?

RG: My friend Tony Slide and I called on Elsa Lanchester in the early 1970s. She said that her garage was full of old takes for The Night of the Hunter and that she wanted to clean out the garage. We agreed to take the footage, and she shipped it to the AFI in Washington. I started putting the takes together just before I left. They stayed there for several years, but then the AFI sent them to me in California, where I continued my efforts. Through the years, students actually worked on putting them back together. The sound was separate from the picture, and everything was out of order. Finally, I assembled a program, which The Criterion Collection has released.

I enjoyed working on Hawks’ The Big Sleep—both versions of it. The non-standard version was shown to the troops at the end of World War II before it was released to any theaters. The studio ultimately redid a lot of the scenes and made it a lot more fun to watch, even if it became even more confusing than it was before.

We got nitrate material of the 1946 version from Warner Bros. But also, surprisingly, we got an almost-complete print of the 1945 version. We weren’t supposed to get it, and Warner Bros. wasn’t supposed to have it. The only thing missing from the copy we obtained of the 1945 version was the opening title sequence, which gives a different credit for the actress playing Eddie Mars’ wife. However, Warners hadn’t kept the original titles. So, we wound up just copying the title sequence from the ’46 version. That’s the only thing wrong with the earlier version that is viewable today. I realize now that if anybody has a 16mm print of the film that was shown during World War II, that print’s title sequence may be correct and could be copied and inserted to fix the error. But nothing like that was available to us at the time.

John Ford’s My Darling Clementine was interesting because we likewise had two versions of it. We preserved both the standard release version and an earlier version that had been edited by John Ford before Darryl Zanuck took it over.

TDR: I did want to segue to a handful of more biographical questions. Did you attend a lot of film screenings growing up?

RG: I remember that my family would sometimes rent a movie projector and a film and then run it just for ourselves. I recall seeing Meet John Doe by Frank Capra and Hellzapoppin’ with Olsen and Johnson. Also, I went to the movies regularly with my parents. I remember that, in 1947, we went to see Road to Rio with Crosby and Hope. I later worked with the original camera negative of that film and preserved it at UCLA. That was a very interesting experience, returning to that film after thirty years.

But yes, my family used to go to the movies all the time. We were in a small town, Hanover, Pennsylvania, that had only two major theaters, the Park and the State. The Park Theatre showed Paramount, Twentieth Century-Fox, and United Artists films, while the State Theatre presented M-G-M, Warner Bros., RKO-Radio, and Columbia films. A third tiny theater, open only on weekends, presented Republic, PRC, and Monogram films as well as “B” pictures and serials.

For foreign films, I had to travel to York, Pennsylvania, as there wasn’t enough interest in my hometown to sustain those screenings. The first Chaplin film I saw was in 1950 in York: City Lights.

TDR: Could you discuss some of the friendships you made throughout your life with prominent figures in film?

RG: I became close friends with the actor Norman Lloyd, and I knew him very well from around 1979 until his death two years ago at the age of 106. He was an amazing person who knew Chaplin, Welles, Hitchcock, and Renoir, and everybody. He was a very bright person and had all kinds of stories to tell. He drove a car until he was 98. And he was in very good health until just before he died. He’d probably still be alive if he hadn’t been worn down by a fall he sustained at 104.

I worked on restoring several films in which Norman Lloyd appeared, including Jean Renoir’s The Southerner. I met Norman originally through Jean Renoir. Norman appreciated what the Archive was doing, and he used to come to our screenings and do introductions now and again.

As for my connection to Renoir: In the summer of 1968, I programmed a Renoir series for the Dartmouth Film Society. He and I corresponded at that time, and he expressed his approval of a series brochure that had turned out nicely. But I didn’t get to know Renoir really until I moved to Los Angeles.

Tony Slide and I met Jean Renoir and his wife through a contact. This was just a year or so before Renoir died. He would have people come into his home and screen films for him, and I started doing so. I brought 16mm prints from my own collection or from UCLA, which I would run through Renoir’s personal RCA 16mm projector. The last film I screened for him was Fritz Lang’s M. I don’t know what he thought of it. I didn’t speak to him very much, but I did speak to him. He was very nice but very old. And I knew his son, Alain Renoir, and now I know his great grandson, Matthew Renoir. So, I have known most of the Renoir family, actually, except for the painter.

TDR: Finally, may I ask on what projects you are currently working at the Packard Humanities Institute?

RG: I’m happy to say that we’re using digital technology, going back to some very rare 16mm features from the 1920s that are full of scratches and so forth. We’re restoring them digitally. It’s part time, and I enjoy it.

TDR: Thank you very much, Mr. Gitt, for taking the time to talk with The Review.

RG: Thank you.

Great interview! Very thorough. Thanks!