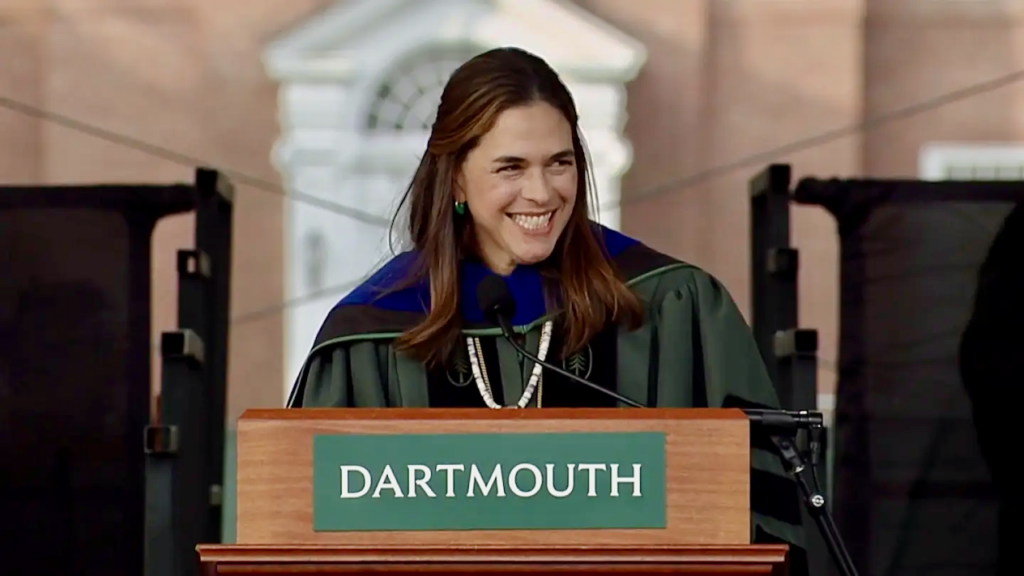

On Friday, September 22, Sian Leah Beilock was inaugurated as Dartmouth’s 19th president in a grand ceremony that lasted nearly two hours. Over the course of the event, a variety of speakers—hailing from Dartmouth, broader academia, the government, and elsewhere—took to the podium to extoll the virtues of our College and, often more pointedly, of our new president. Ultimately, President Beilock herself delivered an address in which she laid out a detailed platform for her presidency.

This issue contains an article that describes and analyzes the inauguration ceremony, and its various addresses, both sequentially and as a collective whole. However, for the purposes of this column, I wish to underline a single subject that emerged in the event’s oratory—more correctly, almost uniquely that of President Beilock. This subject was, from my perspective, the elephant in the room (or, rather, on the Green): free speech.

In an interview with The Dartmouth Review on December 15, 2022 (published in TDR, 1/27/23), then-President-Elect Beilock asserted her belief in the utility of exposing students to ideas with which they disagree. She contended that such exposure must be effectuated by the presence of, in her idiom, “brave spaces,” an obvious but important countermeasure to the hackneyed concept of “safe spaces.”

In the months following her interview with The Review, when Beilock was asked for a preview of her plans upon assuming Dartmouth’s presidency, she would frequently emphasize the import of creating such “brave spaces.” It was at last Friday’s inauguration that she formally committed the College to that aim.

I am pleased to report that President Beilock went further still in her address on Friday: She asserted that, in the “Chicago Statement” on free speech (widely viewed as the benchmark for free and open dialogue on college campuses), the articulated principles “don’t go far enough.” To that end, she announced that Dartmouth will seek to “facilitate, practice, and teach dialogue across difference” by way of several campus initiatives, most notably the “Dartmouth Dialogue Project.” This project, Beilock said, will develop students’ skills in “open, honest, and respectful communication both in and out of the classroom.”

To be sure, this was an admirable passage in Beilock’s address, suggesting as it did that the new president wants to do more than pay mere lip service to the cause of free speech. However, it is regrettable that the embrace of free speech which Beilock advocated received no substantive mention by other speakers at the inauguration ceremony. By contrast, many of the speakers heartily enumerated and endorsed the president’s countless other initiatives, especially those related to diversity and inclusion.

For my part, happy though I was to hear the president’s well-conceived remarks about open dialogue, I have questions about how her proposed approach to free speech—in effect a top-down approach—will function. It is all well and good that President Beilock wants to “support faculty in teaching controversial topics in their courses.” But by what means exactly are faculty members going to fairly teach controversial topics, and which faculty members will be doing so? To inculcate open- and fair-mindedness in students, surely faculty must first model the same. Moreover, is the problem of which Beilock speaks solely a failure to tolerate different viewpoints, or is it not also that so much is unduly politicized in academia today? Are the noble objectives of the “Dartmouth Dialogue Project” and its host of curricular and co-curricular programming really going to spread to courses that do not topically relate to politics but do stifle free speech? I’m doubtful. I remain rather more hopeful that Beilock’s philosophy will serve to remedy and reduce some of the one-sided excesses in the administration that we have witnessed in the past several years—a change which will itself serve as a model for positive discourse on campus.

My questions about top-down programming aside, I wish to note that a similar structure has in fact succeeded at least once before in the history of the College. In 1947, President Dickey famously—and, by common consensus, quite successfully—imposed the mandatory “Great Issues” program of study for seniors. In so doing, he directly exposed seniors to pressing international questions and concerns of the era. Beilock’s “Dartmouth Dialogue Project” strikes me as a similar undertaking. Indeed, if she and her administration treat the project with the same degree of seriousness and thoughtfulness as Dickey did his, it has the potential to be groundbreaking.

While I—and, I’m sure, many others—have outstanding questions about the specifics of President Beilock’s plans, I was overall impressed by both the thrust of her remarks and those details which she did provide. I have high hopes that my optimism about the Beilock administration will be rewarded.

Be the first to comment on "Editorial: Beilock’s Approach to Free Speech"