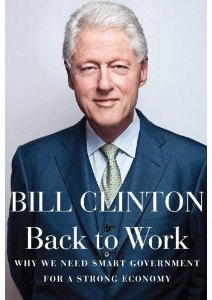

In case you haven’t heard, Bill Clinton is at it again. Last month, he released his third book since leaving the Oval Office, making his post-presidency literary resume nearly as long as the list of botched humanitarian interventions he accrued as commander-in-chief. Not one for crafty titles, the author of My Life and Giving has entitled his new hardback on restoring the American economy Back to Work. Within its 200-pages, the former President espouses the rather dubious notion that big government can be so much more than the inept fiscal incinerator that history has proven it to be; rather, when unleashed in “smart ways,” Washington bureaucrats can actually be a force of good.

Reality check notwithstanding, President Clinton has recently blasted around the country, jumping from one book-signing event to another while promoting what promises to be another hopelessly ineffectual book from a hopelessly ineffectual leader. We at The Dartmouth Review would be content to let the former president founder in his efforts to encourage the oxymoron of intelligent government if it weren’t for one anecdotal comment that was made in a recent interview.

Last Tuesday, in response to questioning from Aaron Task of Yahoo Finance, the former president went on the record as saying:

My taxes were cut a lot in the last decade and my income went up a lot. I believe people like me should pay, not because it’s a bad thing to be successful, but because the country’s made us successful and we’re in the best position to help do something about the debt and invest in the future of the young people to give them a better future.

Within hours of the interview going live online, lefty bloggers across the country sharpened their pencils and wrote elegiac pieces extolling the wisdom of the former president. “Why can’t today’s politicians see the writing on the wall?” one poster bemoaned. “[Bill Clinton] points out the obvious argument for why the rich need to give back more in taxes. It’s only fair that those who society has benefited should do the most to benefit society.” Another commenter cheered, “It’s about time someone made this kind of argument against the rich and their money-grubbing ways. It’s refreshing to see someone attack them in a new way.”

As repulsively erroneous as the above comments are, their writers are correct in at least one respect. With his rejoinder, President Clinton did more than echo the Democrats’ traditional charge against the wealthy; he put a far more pernicious spin on it. No longer are those on the left content to dabble in the abstractions of a perverted sense of morality that calls the seizing of wealth from those that produce it virtuous. Now, progressives prefer a far more nuanced attack on the merits of an individual’s claim to his own money.

In his defense of his suggestion for higher taxes on the wealthy, Bill Clinton unwillingly provides the nation with a glimpse into the liberal psyche. Democratic dogma holds that private wealth creation based upon the talent, ingenuity, and drive of individuals is not the whole story. Instead, the suggestion has been made that the wealthy only got that way because society preconditioned them for success. Certainly, there is room for merit and diligence in the narrative of affluence, but the primary engine of progress does not lie within the individual, but within the external forces of community. The former president’s use of the active voice when answering with “the country’s made [them] successful,” speaks volume’s to this. To the left, the subject of wealth creation is not the few who rise to build and market a better mousetrap. Instead, it is the society around them which provides the individual with consumers, legal protection, and stability that is deserving of the credit, and therefore an increased chunk of the profit.

Where did such an unfortunate worldview come from? The answer is history.

In recent years, the trend within historical scholarship has been to examine nations of the past in a more egalitarian manner. Rather than studying the upper echelons of society where the decisions that shaped the course of history were made, historians have sought to analyze the plight of the common people on an increasingly regular basis. While there are certainly benefits to such an approach, the modern mentality it has engendered erases them. From this new emphasis upon all of society’s ability to shape the course of history, a distorted sense “bottom-up” significance has permeated into popular thought. No longer do people hear the traditional narratives associated with a John D. Rockefeller, Henry Ford, or Bill Gates. Their talent, their special ability to make ideas a reality, are downplayed as the preconditions that society created are underscored. Helped along by books like Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers, this mentality that denigrates the abilities of the successful while emphasizing the importance of societal conditions has charged its way into popular schools of thought. But at what price?

If we as a culture continue to belittle that special spark that talented individuals possess, we might just find ourselves in a very bad way. Revisionist history would lead us to believe that the now defunct biological theory of spontaneous generation is preeminent. When it comes time for the next great innovation, it is simply a matter of throwing the ingredients that society has generated into a pressure cooker of popular demand, and then watching a lucky few patent and profit from what is inevitably churned out. Within this new dogma, it is enough to simply have the requisite external conditions; the input of a talented individual’s energy and creativity is secondary. What reigns supreme is the need of those in the community and its creation of a forum in which they can be fulfilled. Is this really a mentality that should be cultivated, let alone by a former president?

I think not. But then why do we continue to denigrate the creative talents of those upon whom we rely? Are we really naïve enough to assume that without the “x-factor” that they present, mankind’s greatest achievements will materialize by need and context alone? I hope not, but until we acknowledge that it is not the needs of the many but the talents of the few that support society, we risk alienating the very group of people upon whom we all rely.

— Nick Desatnick

Be the first to comment on "Bottoms Up"