Long after we are gone, the ghost of our time will echo the forgotten chants of “Cigs Inside” across The College’s halls.

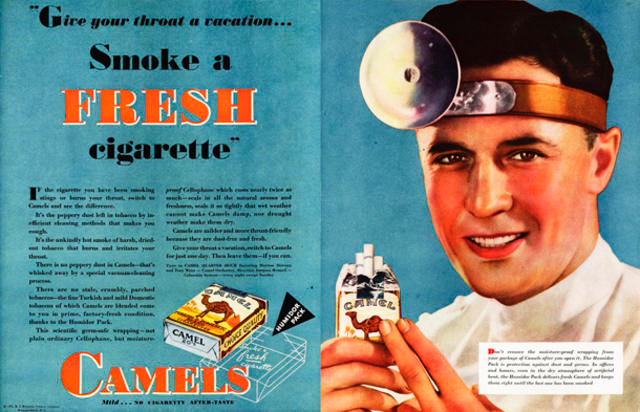

The Dartmouth man has long been expected to be a master of fire. In the brutally cold New Hampshire winters, the sliver of hope and comfort is the heat a fire brings. Students were once expected to chop or collect their own wood in order to heat up their living or outdoor spaces. Despite this no longer being a necessity since the invention of heating systems, the annual Homecoming Bonfire honors the spirit, where students gather around and rejoice at the beauty of warmth and vitality. Fire is thus an integral part of the Dartmouth experience. This tradition further persists in the act of smoking. The cigarette is symbolic of man’s control over fire: in the face of a vast winter landscape, he lights his cigarette and warms his lungs, embracing the cold for he can endure it — even if only for a moment. Furthermore, fire encourages community. For thousands of years, humans have gathered and bonded around crackling fires. Smoking extends this practice as great conversations and experiences can be born out of going through a pack of Camels with friends or colleagues. The sharing of a cigarette or a tobacco pipe is itself a beautiful sight, and even more so with strangers in which bumming a cigarette requires unreciprocated generosity. One shares his fire with another for the sake of camaraderie and community. There is no quote more fitting to describe the role of cigarettes than an excerpt from Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged:

I like cigarettes, Miss Taggart. I like to think of fire held in a man’s hand. Fire, a dangerous force, tamed at his fingertips. I often wonder about the hours when a man sits alone, watching the smoke of a cigarette, thinking. I wonder what great things have come from such hours. When a man thinks, there is a spot of fire alive in his mind – and it is proper that he should have the burning point of a cigarette as his one expression.

This past week, President Hanlon sent out an email debriefing the community on the College’s new “Tobacco-Free Policy,” to take effect March 18th. According to the email, the policy “will prohibit smoking and the use of tobacco products in all facilities, grounds, vehicles or other areas owned, operated, or occupied by Dartmouth,” including all outdoor spaces, as well as public streets and sidewalks within twenty feet of the entrance to a Dartmouth building. It applies to anyone stepping foot on (or near) Dartmouth’s campus and grounds, including students, faculty, staff, administrators, contractors, and visitors. In the meantime, the College hopes to assist current smokers prepare for the coming change by providing them with resources encouraging cessation, including medication for faculty and students, and “Quit Kits,” which are free prepackaged goodie bags filled with everything a smoker might need to get started on the road to abstinence, “such as fidgets, sugar-free gum,” and, for those who are over the age of 18, nicotine replacement therapy gum (limit one per customer). To be clear, it is not obvious whether one must demonstrate they are a current nicotine addict to qualify for the kit, or if the College is handing out free Nicorette to anyone who wants it.

If one were to base their opinions of the College’s new tobacco ban solely on President Hanlon’s January 14th email, they might get the impression that Dartmouth’s primary motivation in preventing the consumption of tobacco-derived products by anyone who steps foot on their grounds is the protection and promotion of the well-being of their community members. Hanlon practically says as much when he writes, “We are implementing this policy because Dartmouth is committed to providing a healthy environment for our community.“ This is misleading. A quick glance at the FAQ subsection of Dartmouth’s new “Tobacco-Free Policy” webpage, under the “Why is this policy being launched now?” subsection, reveals that the sudden launch of the policy is “Thanks, in part, to a 2018 grant from the American Cancer Society as part of the Tobacco-Free Generation Campus Initiative…”

The details of the stipulations and amounts of the grant are, at the moment, a bit hazy, though look forward to a future Review article digging into the gritty details of this arrangement and the ACS’s Tobacco-Free Generation Campus Initiative (TFGCI). From the research we have already done, it seems as though Dartmouth received a maximum of $20,000 from TFGCI. This is only the tip of the iceberg. The ACS, the parent organization of TFGCI, reported $1,152,000 in active grants given to Dartmouth College, not including the $20,000 given as part of the TFGCI grant. Of course, unlike the TFGCI grant, the ACS grants are not specifically tied to the prevention of smoking, though one cannot overlook the sheer amount of cash given to the College by an organization with a sub-group proactively bribing universities across the nation to ban all forms of tobacco on campus.

This is not to suggest that grants funding cancer research are a bad thing. I am very glad that the ACS is funneling so much capital into productive academic research, and who knows, maybe Dartmouth’s grant money will end up funding the cure to the oral cancer I will doubtless develop in my late seventies after a lifetime of smoking pipe tobacco. This does not change the unsurprising yet no less revolting fact that College policy is shaped fundamentally by donors and cash, not by the democratically-given consent and passions of those who comprise the community.

Under the guise of states of emergency amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, authoritarian and democratic regimes alike have consolidated their control: Putin declared himself the president indefinitely, Orbán solidified absolute power through the right to rule by decree, and Xi crushed the Hong Kong pro-democracy movements with little coverage or retaliation. These developments prove how states of emergency embolden actors to make strong-armed moves; the history of Egypt since the assassination of its President in 1981 is a testament to this fact. Since this event, emergency declarations have been the rule — not the exception. While differing in scale and magnitude, similar trends have been occurring at the College: the exile of students from campus with little notice, its silent crackdown on Greek Life and its banning of Dartmouth’s infamous pong, and a concerning inclination to consistently alter plans without consideration of the concerns, finances, and wellbeing of its largest constituents, its students.

Utilizing the chaos of the current pandemic in order to implement broad-based, indefinite policies, the administration has solidified its control over its students’ lives. With many students disconnected from the current campus environment, this reality may not be so clearly obvious, but it is occurring. Our voices cry out in the wilderness, but they are not heard. In this context, it is difficult to receive the news of a sweeping tobacco-free policy as reflective of The College’s intent to “provide every opportunity possible for community members to protect themselves.” This vision of a tobacco-free campus — or more appropriately, a nicotine-free campus, as the ban implements measures that appear far broader than just the prevention of smoking tobacco — is tainted by not only the College’s lack of concern for the voices of its students, professors, and other employees but also its ignorance of both the individual and communal experiences that define the College and its history.

If the College sought to mitigate the risk factors of a “variety of life-threatening diseases, including COVID-19,” they could not simply end this mission by banning tobacco on campus. For example, obesity is considered one of the leading causes of preventable death and also increases the risk of long-term impacts from COVID-19. The College’s current language regarding the policy would necessitate action to combat obesity as a risk-factor, which could include banning a variety of unhealthy food products currently offered at the dining halls. Obviously, mandates like this example would produce outrage because they would deny a student’s ability to make his own choices as well as would significantly hinder certain students’ quality of life and comfort. Although fewer people may be affected by the tobacco-ban, the same logic applies. It is, in fact, the same fallacy that allows authoritarian regimes to further extend the scope of their power over the people. The College’s decision introduces a slippery slope that would detrimentally impact the already crumbling relationship between the administration and students. It is additionally important to remember that students are not the only ones affected. Faculty and other workers also smoke and use tobacco products — and in many cases, have been doing so for years. To assume that this sudden decision is fair to those whose lifestyles have included smoking is preposterous. The delayed March implementation of the policy is merely appeasement to distract from the larger issue at hand: that the College can readily make sweeping, life-altering decisions and expect subservient cooperation.

It is crucial to analyze the ambiguity and problematic nature of the language The College uses to justify and establish the tobacco-ban. Citing “cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos, hookahs, chewing tobacco, snuff, snus, dissolvable tobacco, and electronic smoking devices” as all examples of now restricted products, the College has declared war on nicotine itself. The act of smoking is not the target, but rather the entire apparatus. In regards to smoking specifically, the only justification to ban it without infringing on individual freedoms would be that it can harm others. First, second-hand smoke is mainly associated with cigarettes, which folks usually use outdoors, minimizing the risk of harmful exposure. Second, consumed tobacco products cannot harm those in the presence of the user.

Regardless of these facts which will be discussed in more detail, the solution is not to ban tobacco as a whole. As responsible, college-educated students, those who do not want to risk second-hand exposure can simply remove themselves when those around them are smoking or using tobacco. However, the College has decided that instead of allowing students to be accountable decision makers, the solution is to medicate those who will not or cannot conform. Touting the “cessation resources” available, the College offers another form of drug to restrict students from consuming a drug that they voluntarily choose to use.

Long gone are the days of In loco parentis, wherein colleges take on parental responsibility over their students. Since the 1960s, this power has deteriorated due to the courts granting students further constitutional rights, restricting a university’s ability to regulate student life. Nevertheless, the College, especially with policies like the tobacco-ban, are expanding their control over students, transforming them into wards of the institution. The College should not be accountable for the consenting, personal decisions of adults — and its institutional power and influence should not change that fact. If decisions like these continue to be made based on shielding its students from the potential dangers of life choices, we lose a valuable phase of maturing and developing into Dartmouth men and women prepared for reality.

Moreover, the way the College applies the ban to not only spaces owned and operated but also “occupied” by Dartmouth is unsettling. Not even the public roads and sidewalks or the Green appear safe from the ban, which highlights the extent of the policy. Without approval from the City of Hanover, a tobacco-free campus that includes property and spaces not owned by the College is an excessive overreach of power. While they emphasize that “state law allows Dartmouth to establish rules regarding tobacco use on its property,” do they have the authority to control open-air spaces if college facilities merely “occupy” adjacent areas? This ambiguity sows distrust in regards to the College’s rules and infringes upon the beauty of being a student in New Hampshire, where we can embrace nature without the gazing eyes of Big Brother watching over us. The College even demands that students share the responsibility for “enforcing the policy.” Enlisting students to carry out disciplinary policies deepens the current divisions that began with the College encouraging students to report their fellow friends and acquaintances for minor COVID-19 infractions. It is as if the Red Guards of the Cultural Revolution were not a powerful enough lesson against incentivizing those within a society to turn against each other. Or, possibly, the deterioration of student unity works to the best interest of the College’s administration and their goals.

As a result of the ever-increasing number of cases of COVID-19, much discussion in these days of the pandemic revolves around public health and the sacrifices we must make societally in order to safeguard, or attempt to do so, the physical wellbeing of the nation and the globe. Rational actors would not hesitate to agree with the notion that, in at least some instances, it is necessary and worthwhile to curb some individual freedom for the welfare of a society. Participation in a state or system of governance has always required the sacrifice of some negative personal liberties in order to ensure the productiveness and functionality of the whole. More recently, we have seen this problem enacted on a scale unheard of since the attack on the Twin Towers in 2001, and arguably since before even then. Public freedom and mobility has been pared greatly in an attempt to protect the vulnerable from an often-deadly virus and to slow overall infection rates to avoid an overload of the American healthcare system, which has seen unprecedented strain in recent months. Of course, the malinformed have been vocal and occasionally violent in their opposition to social distancing requirements and mask mandates, not to mention compulsive quarantine periods. Still, according to the best models of the virus’ potential for destruction, it seems fairly uncontroversial to suggest that these short-term limitations will be worthwhile in order to curb the long-term devastation posed by the virus.

We want to clarify, therefore, that we are not opposed in principle to the limitation of personal freedom in order to promote public welfare. This is not at all to suggest, however, that any instance which sees a decrease in personal freedom and a respectively marginal increase in public welfare is justifiable. In fact, it is asinine to hold this position; presumably the promotion of public welfare is in the broader interest of individual wellbeing, and if individual wellbeing comes at a greater cost than the improvement in public welfare, such a decision would be irrefutably untenable and internally contradictory. The College’s tobacco ban is just such an instance. As a result of the tobacco embargo, wellbeing can only be promoted in three instances: the decrease in harm to the smoking population, the decrease in harm to the non-smoking population, and the aesthetic improvement of the campus.

In the case of the aesthetic improvement of campus, there is, we suppose, an argument to be made, though it would doubtless be one with which we would vehemently disagree. Some find the sight (or smell, though this is easily enough avoided) of a smoker repulsive, and would prefer the act to be relegated to unseen spaces. Presumably, this is some of the motivation behind designated smoking areas, which force smokers away from the public eye and into a protected and relegated bubble. The TFGCI cites “designated smoking areas” within the jurisdiction of the college as deviations from their tobacco-free criteria that disqualify the institution from their $20,000 grant. Thus, the only solution to the aesthetic repulsion caused by the sight of smokers is to purge them from campus. We don’t think we have to spend too long here explaining why this is a ridiculous reason for banning all tobacco-based products on campus and should not be counted as a justifying point in favor of the College’s decision. Suffice it to say that if you are repulsed by the sight of a smoker then D.A.R.E. may have done a better job than we gave it credit for.

Smoking also causes very minimal harm to the non-smoking population on campus. I am not here denying the malignant effects of exposure to second-hand smoke, which, not only have been researched and rehashed ad nauseum, but also have afflicted me personally in my youth, as I have moderately severe asthma and an aunt that at one time smoked frequently. I do want to stress, however, the complete nonissue that is exposure to second-hand smoke in uncrowded outdoor areas. A crowded building could ban smoking, as other patrons have no choice but to share the same air as the recycled tobacco smoke waste. It may be reasonable to ban smoking within twenty feet of an entrance to a building, as this is a highly trafficked area with frequent bursts of population density, which is part of Dartmouth’s tobacco-free policy and, if I’m not mistaken, was already College policy before the total ban. But to suggest that banning the use of tobacco products (not only combustables, but chew, gum, and any other nicotine-based substance) across the entirety of spaces even tangentially related to the College would greatly, or even notably, improve the wellbeing of pedestrians because of reduced exposure to second-hand smoke, is absurd. It is simply far too easy to avoid smokers in a public setting as is, and many are happy to accommodate the flow of foot traffic by smoking far from populated areas in the first place. This might be a potentially acceptable action to take during the course of the pandemic, as those affected by COVID-19 are at greater risk of respiratory harm. However, as this is not the case in the College’s policy, it is not worth discussing.

The only instance where you may see an increase in wellbeing, depending on your definition of the term, is in the population of smokers or users of nicotine who quit because of the College’s policy. First, many affected by this ban, contradictory to the announcement’s graphic and egotistically paternalistic depiction of smokers, are not addicts, but are those who enjoy sharing a cigarette with friends on the weekend, or who Juul occasionally to curb a jolt of anxiety, or hobbyists like myself who smoke a pipe or cigar irregularly. The long-term health of individuals such as these will not be substantially improved by the College’s injunction; rather, they will merely have fewer means of expressing themselves, exploring their individuality, and unwinding from the stresses of undergraduate study by enjoying a hobby. Furthermore, it is questionable whether the ban will truly benefit those who are legitimately addicted to cigarettes or nicotine (anecdotally, most of whom seem to be working-class college employees and contractors). Sure, they may now have a decreased risk of developing cancer or other complications in their future, something they were already aware of, if, and that is an if, they do quit smoking, rather than trekking out of their way to smoke off college property or risking disciplinary action by sneaking a cigarette. Yet the treatment of this population, much smaller than the entirety of individuals affected by the ban, by the College seems morally untenable and not at all worth the benefits. Not only will the policy encourage further ostracization of smokers and increase the taboo of nicotine consumption, something socially harmful not only to groups we have already discussed but also to those for whom tobacco-use factors into religious ritual, but the College’s plan for countering the fall-out of their ban, stated on the webpage formally as, “Faculty and staff can access a variety of tobacco cessation resources, including medications…”, seems to be to simply drug the poor bastards, a Huxleyan turn barely masked. With all these points in mind, it seems clear to us that the tobacco ban crosses the threshold into action that promotes the public good at a much greater expense to individuality and personal freedom, and is therefore philosophically unsupportable.

Smoking, and the consumption of tobacco- or nicotine-based products in general, has developed quite the taboo within contemporary American culture. What was once a generally accepted practice among all, from the poorest of farm-hands to the wealthiest of aristocrats, has now been relegated to the unseeable and revolting practices of the lower classes, thanks to an unbelievably successful campaign the United States federal government has waged at full force since the Reagan era. While good has undoubtedly come of the American elite’s newfound hatred of smoking (now an icon of white Yuppie culture) in the form of a dramatic reduction in health complications that come as a result of smoking, it seems we are nearing the peak of potential good (if we have not already surpassed it), and now enter the realm of pure limitation of individual freedom for the sake of homogeneity and the promotion of the scientistic sterility that undergirds neoliberalism.

From a portable alternative to the comparatively laborious process of smoking from a pipe, the cigarette has become an emblem of the anachronism of the working class, the stubborn refusal to “believe in science” and follow the professional managerial class into the present. It mirrors the elitist perception of the rural poor as stupid, outdated, smelly, and without place in contemporary discourse. Chewing tobacco has followed the same path, coming to represent the stereotype of the racist Southern hick who dips seemingly in sheer defiance to the Enlightened Liberal. The College’s formal policy, though clearly sanitized for an acceptable and inoffensive presentation to its intended audience, who are also primarily rich white Yuppies, reeks of the aesthetic revulsion that defines the relationship between nicotine and the elite. This is seen most clearly in its sheer refusal to acknowledge the existence of those who smoke occasionally, not out of habit but out of genuine and benign pleasure, and only address the poor unfortunates who, against their wishes to be purified by the wonders of scientism, are too stupid or too hopelessly addicted to help themselves, and thus must be rescued (read, be medicated) by the benevolence of the College.

We like smoking. We particularly enjoy the social aspect, the flavor of a well-blended and thoroughly spiced Virginia, the focus it lends us, the consistency of its ability to take the edge off a particularly violent panic attack. However, even if we had never smoked in our lives, even if we personally found the experience disgusting, we would be just as opposed to the cultural objectification and infantilization of adults who consensually partake of tobacco. No being with agency should be subjected to such subtly toxic subversion by a wealthy, homogenous elite. No culture should have to forsake itself at the behest of a more powerful Capitalist Scientist. Here, in this article, we have enumerated and elaborated on our grievances with the College’s nicotine ban. We at the Review support the freedom of students, faculty, staff, visitors, and all who step foot on campus to not sacrifice their individuality for the sake of sterilization, yes, even if that means smoking. We at the Review support the democratization of College decision-making and oppose recent efforts by the Administration to ignore the desires and concerns of the Dartmouth Community. We at the Review oppose wholeheartedly the College’s nicotine ban (or at least, most of us do). We strongly encourage the reader to contact the College expressing dissent, to force the Administration to recognize the collective voice of the community instead of unilaterally shoehorning policy influenced by wealthy shareholders and organizations that provide grants.

If you are an employee, as the Tobacco-Free webpage states, voice your concerns to your immediate supervisor or Human Resource Consultant (employees can find this information at https://www.dartmouth.edu/hrs/empsupport/index.html). If you are an undergraduate student, I encourage you to contact your House Professor (https://students.dartmouth.edu/residential-life/house-communities/our-houses) and/or your Undergraduate Dean (https://students.dartmouth.edu/undergraduate-deans/department/undergraduate-deans-office). All others should, as the webpage stipulates, address their concerns to the Office of Community Standards and Accountability (community.standards@Dartmouth.edu).

Read more about the ban here: https://dartreview.com/college-nicotine-ban-leaves-students-fuming/

Sir, this is a Wendy’s