Disclaimer: The author is currently taking a class with Professor Levey, and he has provided input on a manuscript of A Genealogy of Violence.

It it easy to forget that the professors teaching your classes are primarily scholars working continually to contribute to our understanding of the world. In the sciences, this is more easily understood — there, professors are attempting to discover concrete facts about the physical world. In the humanities, however, especially philosophy and political theory, which reason abstractly about abstract facts, this is not always so evident. But there has been some outstanding work published by Dartmouth scholars in this area over the past four years. In this article, I’ll examine three recently-published pieces of philosophy or political philosophy written by Dartmouth professors. These are neither exhaustive nor representative — except insofar as they represent Dartmouth’s scholarly output as high quality — and were chosen mainly because each is accessible to the non-philosopher.

One of these is “The New Conspiracists” (2018), co-authored by Dartmouth Professor of Government Russell Muirhead and Professor Nancy Rosenblum. Published in Dissent magazine, the article argues that Donald Trump’s use of conspiracy-talk in the service of his presidency is unprecedented. But what is remarkable about this, according to the authors, is that there is no theory behind the new conspiracism. There is usually no evidence for what is alleged — even if there is, evidence is not required to make use of the conspiracy politically. Further, there is no explanation for the conspiracy offered — no targeted claim that, say, the FBI in particular has problems with political bias. Rather, the new conspiracism is absolutely general and, as it were, theoryless: it is not so much a theory of events but an overriding attitude towards them. Because of this, the authors argue, the new conspiracism has the general effect of undermining trust in institutions. Institutional checks, after all, are just what the President is reacting against in his conspiracism.

Thoughts that the United States in particular has a weakness for paranoia in politics are not new — perhaps the most famous of these is Hofstadter’s “The Paranoid Style in American Politics” (1964) which was in partial reaction to Goldwater and McCarthyism. One might question, then, just how “new” conspiracism in American politics is. And there are surely some similarities between the effects of the latter and the effects the author ascribes to Trump’s conspiracism: both undermine faith in administrative government. But the central distinction between new and old conspiracism still holds and is, I think, right. McCarthyism’s attack on the administrative state was grounded in the conspiratorial theory that too many officials were communists. Attacks now are grounded on no such theory. And it is in this feature, the generality of “fake news” and charges like it, that the danger for American institutions consists in. Because, although general, theory-less conspiracism now serves the Republican aim of undermining trust in big government, it is so content-free as to also undermine trust in Republican party institutions and in conservatism as a whole. One might disagree, I think, with the article’s claim that this destructive distrust of political parties, “malignant anti-pluralism,” does not share significant features with progressive attacks on centralized power. And it may be wrong in general to suggest that none of the so-called conspiracists offer productive solutions to “drain the swamp” (although the piece rightly observes that Trump has shown little interest in doing so). But his thesis overall is insightful about the current challenges to public discourse in the United States, and the piece is a worthwhile read even for those less averse to Trump than the authors.

The sharp effect of conspiracism on the public mind is surely due to our expectation that everything has an explanation (which conspiracism alleges to be hidden) — every fact has an explanatory ground. This principle — the principle of sufficient reason (PSR) — was the subject of an article by Dartmouth Professor of Philosophy Samuel Levey in Philosophical Review. The piece was published in 2016 and selected by The Philosopher’s Annual as one of the ten best philosophy articles of the year. It focuses on one salient challenge to the PSR: if everything has an explanation, then the set of all contingent truths has an explanation. But this is incoherent since the explanation is either necessary, which is impossible because then all contingent truths would be entailed by a necessity, or contingent, which is impossible because then the set would contain the explanation and therefore explain itself. Therefore, not everything has an explanation and the PSR is false. Levey argues that far from being a reason to reject the PSR, this argument reveals to us something fundamental about the concept of contingent truth — namely, it is indefinitely extensible. A concept is indefinitely extensible when for any totality of things which fall under the concept something satisfying the concept but falling outside the group can be identified by reference to the totality. Levey reframes the argument against the PSR as an argument showing we cannot exhaust the concept of contingent truth because it is so extensible — we can always identify a non-member of a set which is created by it. Levey takes from this and other considerations that the principle of completeness — that there is such a thing as all contingent truths — must be rejected in this case.

It’s not difficult to see why this paper was highly recognized. In particular, the application of set-theoretic concepts and arguments from analogy with set theory are fascinating and powerful. Levey argues that, if we accept incompleteness, then we may have to reject some metaphysical arguments which identify an explanatory ground of the totality of contingent truths — he identifies one in Leibniz which is suspect. He hints at further implications for theology (if completeness is rejected, then there is a problem for God’s omniscience) and philosophy (incompleteness seems to threaten more than Leibniz). The piece is also extremely clear and accessible — especially considering its subject matter — and should be read by anyone with general philosophical interest.

The previous two pieces focus in large part on our epistemic limitations — ndeed, epistemic failure (post-truth, alternative facts) seems to have come to dominate the national psyche. In the book A Genealogy of Violence and Religion: René Girard in Dialogue (2018) and a 2015 column in the Washington Post, Dartmouth Professor of Government James B. Murphy focuses instead on the social conditions which give rise to conflict. Both works examine the thought of René Girard, an anthropologist who theorized about how human desire becomes conflict. The column explains Girard’s thesis on religion: religion does not cause violence, but it is a function of violence. Religion, that is, sublimates and governs the violence which emerges from human conflicts. Girard’s theory of scapegoating — in which the internal conflicts of a community become focused on one victim — provides the framework for this theory. For it is clear by this framework that in Christianity we get the inversion of the scapegoat — the perfect being, perfectly blamed and sacrificed for all sins.

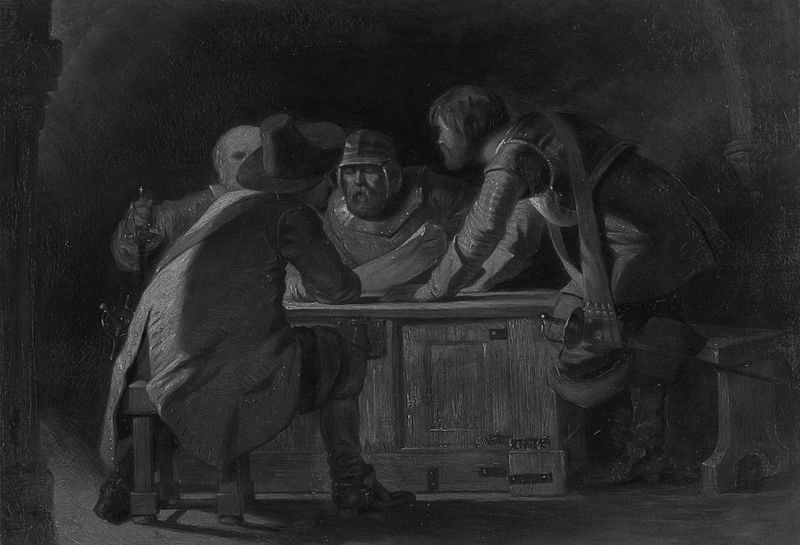

The book, published by Sussex Academic press, offers much more detail than the article. The book is constructed as a dialogue — Girard is in it a character facing off against adversaries such as Freud and William James in defense of his views. In this respect, the book is less straightforward than the article (or, say, a book which aims to systematically lay out Girard’s thought). But it is more than proportionately more rewarding: ideas come to life in dialogue, and Murphy is brilliant in bringing us to an understanding of the ideas from the inside out, as it were. One of the first chapters, for example, consists in a parable which rehearses the generation of religion from a primordial conflict and brings Girard’s account to life. In this dialogue, the interplay of ideas becomes entertaining and accessible — Murphy’s book is highly recommended.

Be the first to comment on "Conspiracy, Truth, and Violence"