In a 2004 interview with The Duke Chronicle, Professor Robert Brandon responded to a question about faculty hiring policies by noting, “If, as John Stuart Mill said, stupid people are generally conservative, then there are lots of conservatives we will never hire.” His remarks touched off a firestorm within the media and led more than one rightwing blogger to conclude that American universities were “fundamentally hostile” to perspectives outside of “a narrow range of explicitly progressive political views.”

Although over ten years removed from the debates of today, assertions like these have long rung true in the minds of many young conservatives. To them, it is a basic fact that the college campus is not the most hospitable environment for the right-of-mind. Ever since the tumult of the 1960s and the rise of the youth “counter-culture,” the academy has stood as bastion of American liberalism and a “no-fly zone” for those who lean to the right of center. Such an orientation has produced a wealth of political controversies and has made conservatives feel as intellectually unwelcome in the Ivy League as Socrates was in Thessaly.

Why is this the case? Is it – as SUNY-Albany’s Ron McClamrock reasoned – that “lefties are overrepresented in academia because on average, [they’re] just f-ing smarter?” Or is it – as Washington Post’s Chris Mooney contends – that Republicans can’t “distinguish between legitimate research and ideologically driven pseudoscience?”

Somehow, neither of those explanations seems to cut it. Beyond the fact that both are devoid of the very rigor that McClamrock and Mooney insist conservatives are incapable of, they are missing a key piece of the puzzle: the psychology behind liberalism’s popularity among the young.

Ever since the Summer of Love and Janis Joplin made “sticking it to the man” look cool, college kids have been drawn toward progressive politics like moths toward an open flame. Peer pressure is a big piece of this appeal, as is the intense nostalgia for the days when there was actually a nation-wide draft to protest. But the most important factor by far is a sense of youthful optimism that American liberalism channels so effectively.

Millennials today want nothing more than to feel like they are making a difference in the world and – just like their parents and grandparents before them – aspire to be ambassadors of the future. For this reason, rather than following Ronald Reagan’s lead in selling their bonds, they get fired up to go catch Joseph Kony and join what they believe is the progressive zeitgeist. Slogans like “Hope” and “Change” appeal to this spirit with aplomb. “Drill baby drill” and a “return to normalcy,” by contrast, look old, static, and oppositional, and serve only to cast conservative principles as an obstacle to be overcome rather than as the solution to our problems.

This dichotomy has put the political Right on the defensive on campuses across the country. At Dartmouth, it has even led some to dismiss it as the ideology of “old dead white men and even deader ideas.” But is this characterization really fair? We at The Dartmouth Review think not.

As the College’s only independent publication and one that has a long history of redefining the focus of student debate, The Review encourages a different type of conservatism, one that is as intelligent as it is innovative. New staffers are often surprised to learn that our meetings bring together writers from all sides of the ideological spectrum to discuss politics over beer and pizza. They don’t come because it reminds them of their grandfather’s Republican party or their drunk uncle’s rants about the NRA. Instead, they come because they find a group of peers primed and ready for debate about the key issues that Dartmouth faces today.

It is this intellectual tension that is at the core of The Review’s conservatism. Rather than a watering hole for political contrarians and progressive spoilers, the paper aspires to be a source of critical thought and reflection on a campus that sorely needs it. We aim to cultivate a healthy respect for tradition and apply our regard for individualism, free speech, and the life of the mind to the pursuit of contemporary solutions. In so doing, our goal is to make the principles of conservatism relevant to student interests by, as the corruption of Lu Xun’s line goes, distilling its old wine and putting it in Keystone Light cans.

As The Dartmouth Review’s enters its thirty-fifth year of publication, we would like to renew our pledge to these principles. Contrary to the views of the Professor Robert Brandon’s of the world, the paper aspires to be far more than just a doormat put out by a bunch of angry partisans; instead, it hopes that the debates it has internally can inspire similarly critical conversations within the student body as a whole. After all, the same John Stuart Mill who derided conservatives for their stupidity also noted that “the peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is that it is robbing the human race… of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth…” The same is true for The Review’s mission. It exists to ensure that a healthy clash of ideas continues to take place among students on campus and that the Dartmouth’s pursuit of truth is all the better for them.

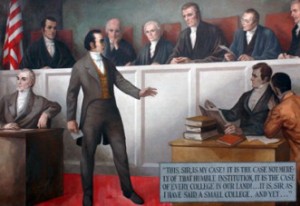

In the end, Dartmouth is indeed a small college and now more than ever it needs the help of those who love it. With that end in mind, Dartmouth’s Review looks forward to its continued contributions to campus and eagerly awaits any and all opportunities for the exchange of error and truth in the year ahead.

Be the first to comment on "Dartmouth’s Review"