Among the Professors hosted at Dartmouth are some truly gifted intellectuals, standouts in their fields with resumes replete with contributions to the academic literature. Yet, some professors are on an earlier part of that journey towards notoriety, and are still attempting to make names for themselves in their fields.

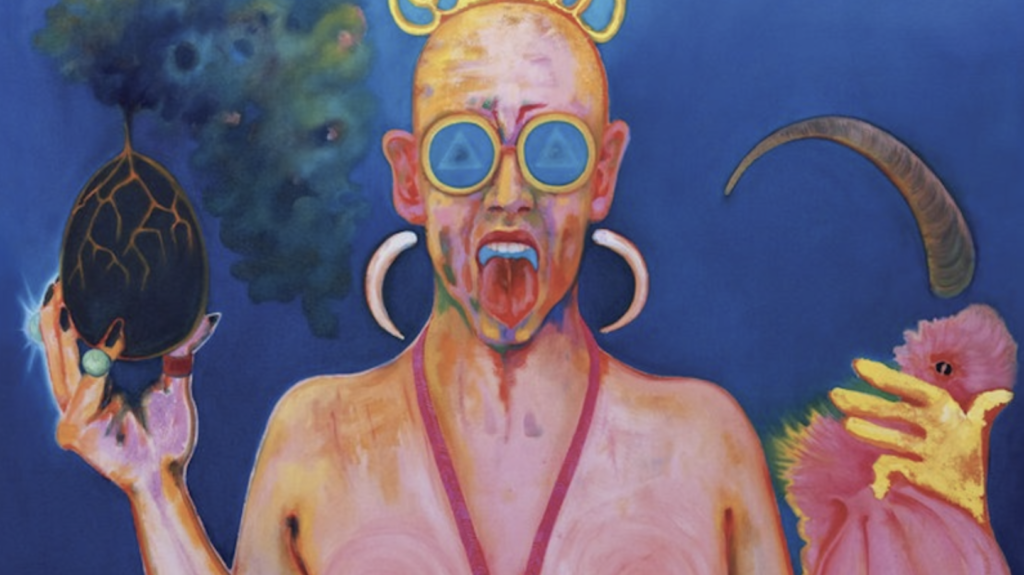

One such figure is Cesar Alvarez, an associate professor of music and creator of the recent album egg, announced on Dartmouth’s website and published online for all to listen to. The album is difficult to summarize, to say the least. While often such difficulty arises from the complexity of a work, it is with no joy that this writer reports that in egg’s case this difficulty arises from the simple fact that the album lacks little of real substance. It is not a collection of groundbreaking tracks, but rather an imitation of earlier and superior postmodernist and alternative music. It joins a long list of overly synthetic, aimless, and unstructured work put out by would-be avant garde artists across the western hemisphere. While not lacking entirely in quality of craft, certainly some talent is required to apply synthesizers at every possible opportunity, the album is bereft of inspiration and real creativity.

From the first track, egg establishes itself as an album dominated by self-pity, alienation, and aimlessness. Alvarez opens with something of a frame narrative, describing his pockets as full of wrappers and remnants of experiences. The song, then, can be viewed as him picking apart these memories.

Alvarez seems to be considering the apparent difficulty of living outside of the constraints of “normal” life, and is stuck between diverging further or collapsing back into conformity.

The song waxes on and on, with Alvarez repeatedly talking to an unnamed you, perhaps himself, perhaps a partner. While the song has some clever elements, it is nothing that has not already been done a thousand times.

Moreover, the song is lacking in any rhythm, beat, or lyrical composition that would make the experience of listening to it actually enjoyable. Alvarez changes the pace of his speech and of the music at seemingly random points, speeding up when saying long words so as to cover up for the fact that the lines have uneven numbers of syllables. Certainly, it is possible for songs that are essentially free verse put to music to work. While we cannot expect all such songs to equal Life on Mars in their quality of writing, one is justified in expecting the first track of an album to be better written than a middle school Haiku. The number of times that Alvarez wants to say a complete sentence but doesn’t want to fit it into one breath, and so separates it into two lines with an awkwardly long pause in the middle verges on aggravating.

The album continues on in much the same vein. Each track sounds different, the album is nothing if not diverse, and somewhat jarring. However, each possesses the same fundamental lack of points. Much of egg is essentially free verse poetry put to music and like much of such poetry, and essentially all written in the 21st century, it is generally incoherent, and unpleasant to read, or in this case, to listen to.

Alvarez relies on synthetic effects to hide the simple fact that his lyrics are largely banal, and bereft of anything of real value. For a quintessential example of the album’s lyrics, look to the opening stanza of “You are a Rainbow Too,” the eighth track of the album. There, Alvarez spends approximately a minute listing traits he ascribes to rainbows. While he certainly intends to convey a meaning, contributing to the overarching ode to the subject “you” that is the focus of the song, the stanza, followed by another stanza that merely lists traits ascribed to the object of the song, seems to be more of an attempt to play for time than any real artistic intention.

Perhaps this kind of composition is typical of new age music. If so, Alvarez has at least not succeeded in making that genre any more interesting.

Alvares can be credited for his attempt to convey true and heartfelt emotion. Among the muddled lines one can find nuggets of real expression. Yet, egg fails in conveying his feelings to the audience in a way that fosters sympathy. There is scant mention of hope to counteract the depressive dogma that dominates each track, as Alvarez invites the listener only to join him in alienation from the “normal” world. Ultimately, it is of little cultural or entertainment value.

“Avant-garde” is a French term for baloney.

Kidding aside, it used to mean something. Now it means amateur night in Podunk.