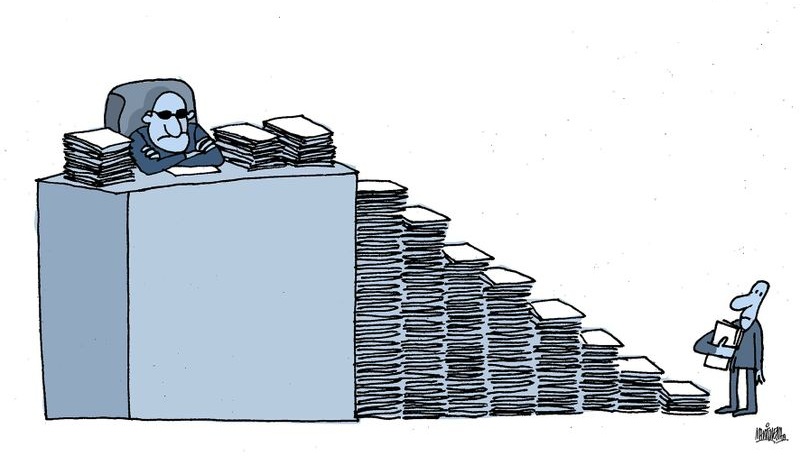

Dartmouth’s seven to one student to faculty ratio is impressively low, but that ratio pales in comparison to Dartmouth’s unreported student to staff ratio, which hovers around three to ten. Put differently, the number of staff at the college is equal to about sixty-six percent of the student body, including both graduate and undergraduate students.

Some of Dartmouth’s 3,500 plus non-faculty staff is practical and necessary. A major university needs maintenance workers, financial officers, career counselors, and lawyers. Other positions, many of which offer lucrative salaries and comprehensive benefits, are not so essential to the College. The College could likely meet its students’ needs without community directors, diversity deans, sustainability officers, and inclusivity deans, or far fewer of them. (Yes, Diversity and Inclusivity are actually separate branches of the bureaucracy, but more on that later).

Federal mandates (which the college has had no say in implementing), have also expanded the bureaucracy. Dartmouth must have a title IX coordinator, and a sexual assault counselor, for example. With all that said, even after our most liberal guesses, it’s hard to find a rationale for the existence of many offices and positions at Dartmouth.

To the average Dartmouth student, the most visible evidence of the College’s bloated administration is the school’s nine “Community Directors” who each make a generous salary and receive housing accommodations from the College. What exactly does a community director do? It depends on whom you ask. The Office of Residential Life’s (ORL) website claims that Community Directors “are responsible for hall programs and student staff selection, training, and evaluation. We provide counseling, advising, and mediation & referral resources for all students in residence. We conduct diversity, education, and outreach initiatives.” The first item that jumps out in this job description is the training for UGAs, Dartmouth’s term for residential advisors, or RAs. The Review has previously written about the absurdity of UGA training, a fluffy, baseless program that amounts to the administration’s attempt to indoctrinate its students. But more importantly, with the exception of those who live on Freshman floors, UGAs do hardly anything at all. Most community directors are currently in clusters with few freshman or none at all, making a major facet of their job almost entirely unnecessary. Moving down the list, the notion that students seek out Community Directors for counseling, advising, and “meditation” (whatever that means) is ludicrous. If anything, students go to their UGA for advice. Although some students may seek out their Community Directors for advice, the authors of this article were unable to find any. Students we spoke to indicated that they only go to see their CD’s when they have to.

This brings us to the most substantive part of the job of community director, the adjudication of minor dorm-related infractions. If you cover your lights, hammer a pin into your wall, break a window screen, or unplug your smoke detector, you will probably be called in to meet with your CD. Although some of these infractions may pose some minor safety issues, it seems that a CD’s primary role is to further the college’s mission to extract as much money as possible from its students through fines. It stands to reason that these infractions could be handled by the college’s Judicial Affairs Office or by other employees in the Office of Residential Life, and that these positons are therefore largely unnecessary.

With the college’s switch to the new housing system, one would think the days of the community director at Dartmouth are coming to a close. This is not so, reports Dartblog’s Joe Asch. The College actually plans to hire four additional community directors, meaning that there will be two for each housing community.

Slightly less visible to the average Dartmouth student, a number of additional administrative offices exist at the College with vague office and job descriptions and minimal accountability that represent misuses of Dartmouth tuition money and donations. The most pertinent examples of this would be the Office of Pluralism and Leadership (OPAL) and the Office of Institutional Diversity and Equity. OPAL, which has eleven full-time employees, “provides academic and sociocultural advising, designs and facilitates educational programs, and serves as advocates for all students and communities,” as it states on its website. Of the eleven positions, one is for the program’s leader, five are for “Assistant Deans and Advisors” to students of various genders and races (Black students, Pan-Asian students, Latino students, etc.), and three are program coordinators. Dartmouth has a Program Coordinator for Gender & Sexuality Diversity and Multicultural Education (CGSE). No one on The Review’s staff has met Sebastian Muñoz-Medina, the man who holds this title. He may be a very nice man, he may be very intelligent, and he even might be very good at his job. But considering his title and the fact that we were unable to find evidence of any specific program that he has put into place, it is hard to imagine that this position is worthy of its place in the College’s budget.

The expendability of OPAL becomes even clearer when juxtaposed with the College’s Office of Institutional Diversity and Equity (IDE). One distinction between the two departments is clear: IDE places much of its focus on affirmative action for both students and faculty. But beyond debate over whether affirmative action is a policy the College should pursue, it is unclear why the Office of Admissions and Financial Aid isn’t sufficient to vouch for the admission of students of various backgrounds. For example, for the class of 2020, touted as the most diverse in Dartmouth’s history, the Admissions Office admitted 51.6 percent students of color, 14.7 percent first generation college and 47.7 percent students who qualify for need based financial aid, with 14.4 percent of those admitted qualifying for Pell grants. In regards to faculty affirmative action, there are already a number of groups, including a strong cohort of faculty members and students, pushing for the hiring of more professors of color, that should be adequate to the task. And if that is incorrect, and it is truly necessary to have a separate, paid voice for affirmative action outside of the administration and admissions department, Evelynn Ellis’ role as Vice President of Institutional Diversity and Equity might be justified, but we certainly don’t need two more employees, a Director and Assistant Director for Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action.

Through our examination of the college’s thickly-layered bureaucracy, we stumbled upon some little known administrative offices that appear to serve the college’s mission and justify the money spent on them. Examples include The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, which oversees institutional research projects involving human subjects and maintains ethical standards and The Technology Transfer Office, which takes technology developed through research or engineering on campus and brings it to the private sector. Dartmouth has not always had these kinds of offices. As the ethical standards of research became tighter in the second half of the twentieth century, The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects became a necessary addition to the College. As Dartmouth’s sciences advanced to the point of putting out cutting edge technology, someone was needed to bring that to the public.

Other administrative departments are wholly necessary entities at the college but have alarmingly large staffs. One such example would be the Office of the Controller, for which The Review counted fifty-nine full time employees. Given Dartmouth’s 4.6 billion dollar endowment and roughly 3,500 non-faculty employees in addition to nearly 1,100 members of the faculty, there is quite a bit to be done when it comes to the College’s finances, but whether fifty-nine full time people are necessary to allow this office to function remains a question. More unnecessary administrators means that the College needs more accountants, benefits specialists (actually in the HR department) and payroll specialists. The six full time employees of student financial services seem to exist mainly to extract as much money as possible from students (many of whom already pay more than 60,000 dollars for tuition) in the form of fines and fees. Yes, Dartmouth parents, part of your tuition money provides for people whose primary purpose is to take more money out of your pockets. However, while the college does need to collect tuition in order to survive whether or not these employees pay for themselves in imposed fines, it is not clear just how many of these employees are required to serve that mission. The college’s bloated administration also feeds into itself, more unnecessary administrators mean that the college needs more accountants, benefits specialists in the HR department and payroll specialists.

One thing that often accompanies a bloated bureaucracy is a lack of results. When offices have a lack of transparency, many staff members, and no clear missions for those staff members, things tend not to get done. The perfect example of a necessary part of the College with rampant bureaucratic inefficiency is the Office of Sponsored Projects. This office obtains funds for research and provides guidance for projects supported by the College. Clearly this part of the institution is needed, but since Dartmouth has just been downgraded from its R1 research rating, it makes you wonder what the thirty-two staff members of the office (for reference, there are only twenty-seven faculty members in the entire biology department) have been doing. There are eight grant managers and accountants, six sponsored research managers, and six assistant directors. We believe that more transparency throughout the administration would be beneficial to everyone. More transparency would ideally lead to a check on these departments, force the bureaucracy into becoming more efficient, and give the students, parents, and donors some comfort that their money is being put to good use.

Another department of seemingly dubious value is the Office of the Chief of Staff for Administration & Advancement. Its stated mission statement is “The Office of the Chief of Staff for Administration & Advancement (OCS) works on behalf of the Dean of the Faculty and associate deans to articulate the needs and priorities of the Arts and Sciences faculty both on and off campus.” This again begs the question, why can’t the faculty articulate their own needs and priorities? The members of our faculty are not children; they can vouch for themselves. Second of all, how much can an administrator side with faculty against another administrator on matters like benefit expansion or pay grading that would pit the two sides against each other? This proposition seems somewhat nonsensical, but the authors of this article have not been able to get any faculty statements or experiences on the matter.

Much of what has been outlined in this article as likely wasteful cannot be supported with hard data. That is because it is so difficult to peek behind the College’s administrative curtain. With so little administrative transparency and accountability, there may be no better way to expose Dartmouth’s outrageously sized and dubiously effective bureaucracy. While it is true that many Dartmouth students come from well-off families, the financial burden on full-tuition paying families can be tremendous, especially when that tuition may well reach $70,000 when accounting for both direct and indirect costs. If tuition needs to be that high, it should be spent on paying higher salaries to professors, upgrading the College’s equipment and physical spaces, or financial aid. If people truly believe that diversity officers are necessary to achieve student and faculty diversity, they should at least be non-redundant and accountable. Dartmouth is hardly the only school guilty of an expansive administrative bureaucracy, but it is among the worst. Getting rid of administrative glut would be a crucial step in allowing Dartmouth to regain what it has lost in terms of public perception, affordability, and educational quality over the past few years. Unfortunately, it looks like the College is heading down the opposite path, cementing Hanlon’s administration among the most destructive in Dartmouth’s history. The administration has historically been much smaller than it is now, at one time having only one all-encompassing Dean of Students. Although colleges now need many employees to function, college presidents also need to allocate their budgets more responsibly. Dartmouth needs someone at its helm who is qualified to run an institution with a one billion dollar annual budget, who can manage that money efficiently, serve its students and faculty, and who will not bleed dry families whose tuition dollars are being wasted.

Be the first to comment on "Excess Administrators"