Editor’s Note: The following is a Review favorite from the archives. Editor-in-Chief Emeritus Nicholas Desai drew this account of Fitzgerald’s visit to Hanover from the Budd Schulberg papers at Rauner Library.

The story of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1939 trip to Dartmouth for Winter Carnival is legendary, even if the best-known version has it simply that the novelist got very drunk in Hanover. Even this condensed form has appeal: the man of letters who does not uphold the supposed dignity of his profession is both comic and tragic. Yet an investigation of the Budd Schulberg papers reveals a tale that, when fleshed out, gains still more gravity and comic appeal.

It’s a yarn that Schulberg ’36 related many times in publications, at conferences, and in fictional form in his 1951 novel The Disenchanted. Like any drinking story, it seems to alter with each telling to provide maximum entertainment, usually through emphasis but occasionally in presentation of facts. (Did Schulberg really take Fitzgerald to Psi U or simply feint in that direction?) But Schulberg, the acclaimed novelist of What Makes Sammy Run? and Academy Award-winning screenwriter of On the Waterfront, tells it well each time. What follows is the ’39 bender according to Schulberg, as drawn from several accounts and rendered using a combination of quotation and paraphrasing. His is the controlling view, since he stuck by Fitzgerald more closely than did anyone else during their brief excursion in Hanover.

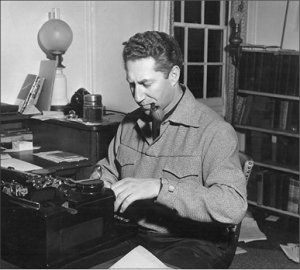

Schulberg was something of a Hollywood prince, the son of a movie mogul who had known only Hollywood, Deerfield Academy, and Dartmouth by the time he had reached his twenty-fourth year. He had graduated from Dartmouth three years before and was working for David O. Selznick, a family friend and the legendary producer who would make Gone with the Wind. This would have led to a career in production, like his father’s, but Schulberg aspired to write. After extricating himself from Selznick, he received a call from the producer Walter Wanger ’15, who proposed making a picture about Dartmouth’s Winter Carnival.

“I always thought of Hollywood like a principality of its own,” Schulberg recollected years later. “It was like a sort of a Luxembourg, or something like that, or Liechtenstein. And the people who ran it really had that attitude. They weren’t only running a studio, they were running a whole little world… They could cover up murder… You could literally have somebody killed, and it wouldn’t be in the papers.

“It was not something on my own I would sit down and be fascinated by, the Winter Carnival movie,” Schulberg recalled, “but it was good money; it was 250 bucks a week, a lot of money—there’s no denying it. I’d been married young. Also it was about my own place, my own college.”

Schulberg later described the Carnival as a “jumping-off point in time for the ski craze that was eventually to sweep America from Maine to California. But somehow in the ’20s, it had gotten all mixed up with the election of a Carnival Queen. And by the time I was an undergraduate, I mean a Dartmouth man, the Carnival had developed into a hyped-up beauty contest, winter fashion show, and fancy dress ball, complete with an ‘Outdoor Evening’ ski-and-ice extravaganza that would have made Busby Berkeley green with envy.

“In 1929 the Carnival Queen was a fledgling movie star, Florence Rice, daughter of the illustrious Grantland. […] In 1937, the Dartmouth band led five thousand to Occom Pond in a torchlight parade to cheer the coronation of a gorgeous blonde with full red lips. The Dartmouth ski team swooped down from the hills with flaming torches in tribute to their Queen of the Snow. Champion skaters twirled on the ice in front of her throne and sky rockets lit the winter night. It had begun to look more like a snowbound Hollywood super-colossal starring Sonja Henie and a chorus of Goldwyn Girls than the homespun college event Fred Harris had fathered a quarter of a century before. One could hardly blame a movie-tycoon alumnus like Walter Wanger for wanting to bring it to the screen.

“Wanger was a very dapper man; he prided himself on being dapper in a Hollywood setting among gauche Hollywood producers. Walter was Ivy League, and he played that role of the Ivy League producer. He had the right threads on for the Ivy League: he was Brooks Brothers. And he had books—real books!—in the bookcase behind him. The only thing that bothered me—well, a number of things bothered me about Walter—but the only detail that bothered me was that he had a large photo of Mussolini framed there on the wall, inscribed ‘To Walter, with the best wishes of his friend, Benito.’ By the end of the year that disappeared into the bathroom.”

Wanger told Schulberg that the script he’d written solo was “lousy” (“I didn’t see War and Peace in Winter Carnival,” quipped Schulberg) and that he would need Schulberg to rewrite it. Schulberg reflected later that no matter how famous or accomplished a writer was in those days, he could be hired for a few days before being summarily fired. So he was feeling lucky merely for hanging on to the job when, one day, Wanger told him that he would be joined by another writer. Schulberg asked Wanger who his collaborator would be.

“It’s F. Scott Fitzgerald,” said Wanger.

“I looked at him; I honestly thought he was pulling my leg.” Schulberg had seen Fitzgerald some years back at the Biltmore Theatre: he came out of a play with Dorothy Parker and looked “ghostly white and frail and pail.” But that was some years back, and when Wanger said, ‘F. Scott Fitzgerald,’ I said, ‘Scott Fitzgerald—isn’t he dead?’ And Wanger made some crack like, ‘Well, I doubt that your script is that bad.’ He perhaps said, ‘Maybe bored him to death,’ or something like that. But Wanger said, ‘No, he’s in the next room, and he’s reading your script now.’” Schulberg went to meet him.

“My God, he’s so old,” Schulberg thought then. “His complexion,” he said later, “was manuscript white, and, though there was still a light brown tint to his hair, the first impression he made on me was of a ghost—the ghost of the Great Novelist Past who had sprung to early fame with This Side of Paradise, capped his early promise at age 29 with what many critics hailed as the great American novel, The Great Gatsby, and then had taken nine years to write and publish the book most of the same critics condemned as ‘disappointing,’ Tender is the Night.”

Fitzgerald finished reading the forty-eight-odd pages of the Winter Carnival script and said, “Well, it’s not very good,” to which Schulberg replied, “Oh, I know, I know, I know it’s not good.” They then went to lunch at the Brown Derby.

Schulberg and Fitzgerald soon discovered that they knew “everybody in common; it was a small town… We talked about so many writers. We talked about the dilemma of the Eastern writer coming West and writing movies for a living, always with the dream of that one more chance, one more chance to go back and write that novel, write that play that would reestablish him—mostly him, a few hers—once again.” Schulberg told Fitzgerald how much he admired Gatsby, and how much it meant to him, and sang the plaudits of his short stories and Tender is the Night.

“I’m really amazed that you know anything about me,” said Fitzgerald. “I’ve had the feeling that nobody in your generation would read me anymore.” Replied Schulberg, “I have a lot of friends that do.” (“That was only partly true,” he said later, “Most of my radical, communist-oriented peers looked on him as a relic.”)

“Last year my royalties were $13,” said Fitzgerald.

They discussed politics, literature, and gossip. “Scott was tuned into everything we talked about—everything except Winter Carnival. Everything. We went through those things, I think, all afternoon. We decided to meet the next day at the studio at ten, and we did but we got talking about everything but Winter Carnival … and we tried, we really tried. But Winter Carnival was the kind of movie that is very hard to get your mind on, especially when you have the excitement of so many other things that are really more interesting.”

It was, in other words, a pleasant time, though they were not doing the work for which they were being paid. “After about four or five days, it reminded me of sitting around a campus dormitory room in one of those bull sessions, talking about all the things we both shared and enjoyed.” An additional danger loomed: though they drew salaries, they had not signed contracts and could be fired at any time.

After a week, Wanger called them into his office to check on their progress. Having done hardly any work, they nevertheless managed not to let on that they had been ignoring the script. Wanger said that they’d better create a central storyline soon, since the entire crew was traveling to Hanover to shoot “backgrounds.” (Said Schulberg, “In those days, they would shoot the backgrounds based on what the scenes were and then in the studio have the actors behaving as if they were at the ski-lift, on the porch of the Inn, and so forth.”)

As to whether they should accompany the crew, Fitzgerald was resistant. “Well, Walter, I hadn’t planned to go to Dartmouth. I’ve seen enough college parties, I think, to write a college movie without having to go to the Winter Carnival.” His resistance was perhaps more understandable if one understands that flying in those days required an enormous chunk of time. Recalled Schulberg, “People today don’t realize what flying was. It was just one step away from the Santa Fe Chief. You got on, and you stopped for refueling several times, and it took about sixteen hours.”

In the interest of staying employed, however, Fitzgerald gave in. “While I felt sorry for Scott,” Schulberg later said, “I have to admit that I was looking forward to going back to Dartmouth with Scott Fitzgerald.” Schulberg’s father, the head of Paramount, was one of the more literary-minded producers in town, and this trait made him proud that his son was working with such a figure as Fitzgerald. Therefore, the elder Schulberg brought them two bottles of champagne for the trip. “As we got on the plane, we were still talking,” Schulberg remembered. “We were talking about Edmund Wilson; we were talking about communism; we were talking about the people we knew in common, like Upton Sinclair and Lincoln Steffens. All of this was going on and on. And it would have been great fun if we didn’t have this enormous monkey—more like a gorilla—of Winter Carnival on our backs. We got to sipping champagne through the next hour or so; it was very congenial. It was really fun, I thought, and then we cracked the second bottle of champagne. We went on merrily talking and drinking.

“Every once in a while we would say, ‘You know, by the time we get to Manhattan we’d better have some kind of a line on this Winter Carnival.’ And we tried all kinds of things; we really did try.” In Manhattan, they stayed at the Warwick Hotel, where they worked for a bit on the story, to no real end. “Scott,” Schulberg said, “You’ve written a hundred short stories, and I’ve written a few. I mean, between the two of us, we should be able to knock out a damn outline for this story.”

“Yes, we will, we will. Don’t worry, pal. We will, we will,” said Fitzgerald. A few college friends called Schulberg, and it turned out they were staying only a few blocks away. “So I told Scott that I would go and see them; I’d be back in one hour. That was one of my mistakes.” When he returned to the room, he found an unpunctuated note that read, from Schulberg’s memory: “Pal, you shouldn’t have left me, pal, because I got lonely, pal, and I went down to the bar, pal, and I came up and looked for you, pal, and now I’m back down at the bar, and I’ll be waiting for you, pal.” Schulberg then found Fitzgerald in a hotel bar a few blocks away and saw that he was in bad shape, not having eaten anything. Nevertheless, Schulberg brought him back to their room, where they continued to drink and work on the script in preparation for a 9a.m. meeting with Wanger at the Waldorf Astoria the next morning.

Despite the drink, the lack of sleep, and the fact that they still had no story by the time of the meeting, they successfully evaded Wanger’s detection and were encouraged to keep working. As they got up, Wanger asked in passing, “Oh, by the way, did you meet anybody on the plane?” Schulberg replied that they had seen Sheilah Graham, a movie columnist. “And Walter’s face darkened, and he looked at Scott and said, ‘Scott, you son of a bitch.’” It turned out that Fitzgerald had secretly arranged to have Graham, his girlfriend, accompany him on the trip, though it might be more correct to say that she was the one who insisted on it. Fitzgerald, in addition to his alcoholism, simply had very poor health. But, in Schulberg’s presence, Fitzgerald and Graham pretended to have met by chance on the plane. Schulberg apologized to Fitzgerald for mentioning it in the Waldorf. “Well, Budd,” said Fitzgerald, “it’s my fault. I should have told you.” Later that day, the pair managed to make the Carnival Special, the train transporting crowds of women to Dartmouth for the weekend. “They were really like a thousand Scott Fitzgerald heroines… The entire train [was] given over to Winter Carnival.”

In 1974, Schulberg revisited Dartmouth and wrote an open letter to the deceased Fitzgerald, reminiscing about their little bender. The Carnival Special was apparently the most noticeable absence from the 1970s version of the event. “Can you hear me right, Scott? No more Carnival Special! No more train loads of breathless dates, doll-faced blondes and saucy brunettes, the prettiest and flashiest from Vassar, Wellesley, and Smith. Plus the hometown knockouts in form-fitting ski suits, dressed to their sparkling white teeth for what we used to call ‘The Mardi Gras of the North.’ Of course there were some plain faces among them, homespun true loves, as befits any female invasion.”

Though Schulberg had told himself he would keep an eye on Fitzgerald’s drinking, the man had nonetheless managed to procure a pint of gin, which he kept in his overcoat pocket. “One thing that [writers are] able to do,” reflected Schulberg years later, is act “like magicians in their ability to hide and then suddenly produce bottles.” Wanger ultimately took Schulberg aside and asked him if Fitzgerald had been drinking, to which he answered no, in a sort of writers’ solidarity against producers. “Another thing I should mention in passing is that Scott may have looked as if he was falling down drunk but his mind never stopped,” Schulberg recalled.

When they arrived, the extremely enthusiastic second-unit director, Otto Lovering, better known as Lovey, met them on the platform, bright and eager. “Just tell use where to go, boys,” he said to them. “We’re ready, we got the crew … we’re ready to go!” The pair stalled and asked to go to the Hanover Inn, where they supposed they might think up a story within an hour or so.

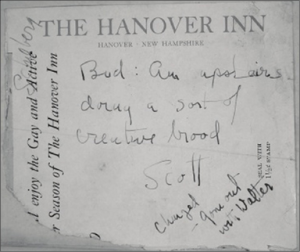

When they got to the Hanover Inn, the entire film crew was already there, “twenty people—more, two dozen—everybody had a room at the Inn.” Except the writers, apparently. “Sir, we don’t seem to have a reservation for you,” said the desk clerk to Fitzgerald, and as a result Schulberg and Fitzgerald ended up in the attic of the Inn. “It was not really a room meant for people to live in,” remembered Schulberg. “It was sort of an auxiliary room where things were stored.” The room contained a single two-level wire bed, a table, and no chair. “Gee, I’m sorry, Scott, but it’s hard to believe they’ve forgotten to get a room for us,” said Schulberg.

“Well,” Fitzgerald quipped, “I guess that really does say something about where the film writer stands in the Hollywood society.” (“He seemed to see it completely in symbols,” Schulberg remembered later.) They stayed in their attic room the entire day, drinking and trying to write. “Scott stretched out on his back in the lower [bunk], and I in the upper, according to our rank, and we tried to ad-lib a story… But the prospect of still another college musical was hardly inspiring, and soon we were comparing the Princeton of his generation with the Dartmouth of mine.”

“Well, maybe this is good,” thought Schulberg. “The booze will sort of run out. We’re up in the attic; there’s no phone; there’s nothing. And maybe if Scott takes a nap, and we take a deep breath, we’ll just start all over again.”

Periodically, Lovey popped his eager-beaver head into the room. “Where do we go? What’s the first set-up?” Schulberg and Fitzgerald simply pulled locations out of thin air with no relation to any extant plot. They told him on a whim to shoot at the Outing Club: “Well, we have a scene of the two of them as they come down the steps and they look at the frozen pond, and we’ll play that scene there.” They didn’t, in fact, have a scene, but Lovey enthusiastically dispatched these errands.

And just when it seemed that they’d drunk all the alcohol, the “ruddy-faced, ex-athlete Professor Red Merrill came into their attic chamber, bearing a bottle of whiskey. Schulberg had been introduced to Fitzgerald’s work in Merrill’s class ‘Sociology and the American Novel,’ and Merrill was a rare Fitzgerald fan. The three of them proceeded to kill this bottle in a few hours while discussing literature. After Merrill left, Lovey ducked in and asked for another set-up, which he received.

Fitzgerald was then supposed to attend a reception with Dartmouth’s Dean (there was at that time only one dean) and several other faculty members with an interest in literature. The idea was that Wanger would present him, and Fitzgerald would describe the plot of the film they were shooting. “It was a disaster since it was pretty obvious that not only was Scott drunk, but when I tried to fill in for him, anyone could see that we had no story.”

“One Professor Macdonald—I remember him well; he was a very dapper man, very well dressed, very feisty—made me feel bad because I thought he was enjoying Scott’s appearance and apparent defeat. He said, ‘He’s really a total wreck, isn’t he? He’s a total wreck.’ But he didn’t say it in a nice way to me. At the same time, Scott looked as if he was absolutely non compos, but his mind was going fast and well, and he made observations about these people that were much sharper, I think, than anything that Professor MacDonald or anybody else could say.”

Then Schulberg realized why Wanger had insisted so strongly on Fitzgerald’s coming to Dartmouth. Wanger had hoped that the College might confer him an honorary degree if he paraded around a writer. “He thought that showing off Scott Fitzgerald, even a faded Scott Fitzgerald, would help him along that road. And now he’d been embarrassed and, in a way, humiliated.”

In The Daily Dartmouth’s February 11, 1939 issue, John D. Hess wrote up an interview with Wanger and Fitzgerald: “The public personality of Walter Wanger ’15 is a disturbing blend of abruptness and charm. At this particular interview, he sat quietly in a chair exuding power and authority in easy breaths, seemingly indifferent to anything I said, but quickly, suddenly, sharply catching a phrase, questioning it, commenting upon it, grinding it into me, smiling, and then apparently forgetting all about me again. In a chair directly across from Mr. Wanger was Mr. F. Scott Fitzgerald, who looked and talked as if he had long since become tired of being known as the spokesman of that unfortunate lost generation of the 1920s. Mr. Fitzgerald is working on the script of Mr. Wanger’s picture, Winter Carnival.”

We now know, of course, that Fitzgerald was not tired, but three sheets to the wind. Having more or less survived the faculty ordeal, the pair proceeded back to the Inn, where Schulberg encouraged Fitzgerald to take an invigorating nap. This he did, lying down on the bottom bunk, and Schulberg, believing Fitzgerald asleep, snuck off to visit some fraternity chums. Sitting at the fraternity bar not long after this escape, Schulberg felt a tap on his shoulder. It was Fitzgerald. “I don’t know how he got there or found me, but he did. And he looked so totally out of place. He had on his fedora and his overcoat. He was not in any way prepared either in his clothing or his mind for this Winter Carnival weekend.” Supporting him by the arm, Schulberg walked Fitzgerald out of the house and down Wheelock Street. He seemed suddenly to regain his energy and suggested having a drink at Psi U.

“And when we got to the Inn … I tried to fool Scott. I was trying to get him back in the room. I said, ‘Okay, Scott, here we are,’ but he realized what I was doing and got very mad at me. We had sort of a tussle and we fell down in the snow, kind of rolled in the snow.” After this incident, they decided to visit a coffee shop. At the coffee shop, “it was humorous in a way, because there were all those kids enjoying Winter Carnival, and everybody was so up, and we were so bedraggled, so down, worried, in despair.” Suddenly, Fitzgerald went into his element, and told “this marvelous detailed, romantic story of a girl in an open touring car (he described how she was dressed). Over the top of the hill is this skier coming down, and she stops and looks at him. Scott described it immaculately well.”

Having finished the coffee, they proceeded back to the Hanover Inn, on whose steps loomed—“as in a bad movie—or maybe in the movie we were trying to write” —none other than Walter Wanger, dressed in a white tie and top hat “like Fred Astaire.” Wanger was “not a tall man, but standing a step or two above us and with a top hat, he really looked like a Hollywood god staring down at us.”

“I don’t know what the next train out of here is,” Wanger intoned, “but you two are going to be on it.”

“They put us on the train about one o’clock in the morning with no luggage,” Schulberg remembers. “They just threw us on the train.” At dawn, they pulled into New York, and Schulberg and the porter had to rouse Fitzgerald and drag him into a cab. They returned to the Warwick they had just left and, apparently experiencing a motif, were greeted with the news that there was no room for them. Perhaps, Schulberg thought later, their appearance and lack of luggage dissuaded the staff. “Somehow the days had run together and we hadn’t changed. We both looked like what you look like when you haven’t done some of the things that one needs to do to keep yourself together.”

“Have you got a reservation?” the desk staff asked. “Well, we just left,” the pair responded, although, Schulberg recalled, “It seemed like a year, an eternity… As I look back, we had no luggage, and the two of us looked like God knows what. I don’t think we’d changed our clothes from the time we’d left Hollywood. I’m sure we’d hardly gone to bed, maybe an hour or so, half-dressed, in the Warwick.” Several unreceptive hotels later, Fitzgerald said, “Budd, take me to the Doctors’ Hospital. They’ll take me in there at the Doctors’ Hospital.” This worked, and a week later Sheila Graham took Fitzgerald back west.

For his part, Schulberg was fired and re-hired. But after Winter Carnival, Fitzgerald was “in major trouble,” said Schulberg. “You know what a small town it is. Everybody knows everybody else’s business, and Scott was extremely damaged.” Yet, touchingly for Schulberg, Fitzgerald continued to send him notes about the film. “He had great dreams about Hollywood,” Schulberg recalled. “It was not just the money. Most of the writers I knew—Faulkner and the others—just wanted to get the money and get out. Scott was different. He believed in the movies …. He went to films all the time, and he kept a card file of the plots. He’d go back and write out the plot of every film he saw.

“Still, the picture itself couldn’t have worked … for by the end of the ’30s, when we haunted the Carnival, it had become a show in itself. And backstage stories are notoriously resistant to quality.”

Schulberg and Fitzgerald remained good friends afterwards, continuing to discuss what they’d always wished to discuss, now without the burden of Wanger or his film. Schulberg remained struck by Fitzgerald’s irrepressible, almost boyish enthusiasm for ideas. “One evening, in West Los Angeles,” Schulberg later wrote, “I was dashing off, late for a dinner party, when Scott burst in. ‘I’ve just been rereading Spengler’s Decline of the West.’ How [could] he maintain this incredible sophomoric enthusiasm that all the agonies could not down? I told him I just didn’t have time to go into Spengler now. I was notoriously late and had to run. Scott accepted this with his usual Minneapolis-cum-Princeton-cum-Southern good manners: ‘All right, but we have to talk about it … in the light of what Hitler is doing in Europe. Spengler saw it coming. I could feel it. But did nothing about it. Typical—of the decline of the west.’”

Schulberg later reflected on Fitzgerald, saying that perhaps “it was to make up for the years frittered away at Princeton, and in the playgrounds of the rich, but, drunk or sober—and except for the Dartmouth trip and one other occasion, I only saw him sober—he never stopped learning, never stopped inquiring.” Schulberg recalled the day he saw Fitzgerald for the last time: “I remember very well, it was on the first day of December in 1940, and I was going East. I’d been working on my first novel. I went to say goodbye to Scott, and he was in bed. He lived in a sort of simple, fairly plain apartment right in pretty much the heart of old Hollywood, off of Sunset Boulevard, right around the corner from Schwab’s Drugstore.

“Scott had this desk built for him to rest around him in the bed, as he was pretty frail and feeling weak, and at the same time found he could write in bed for two or three hours every day.” Schulberg brought Fitzgerald a copy of Tender is the Night, which he had Fitzgerald inscribe to his daughter Vicky. The inscription read “To Vicky, whose illustrious father pulled me out of snowdrifts and away from avalanches.” Dartmouth has this inscribed copy in its special collections.

Schulberg asked how Fitzgerald’s newest novel, which turned out to be The Last Tycoon, was progressing. Fitzgerald answered optimistically, but he spoke little of it otherwise. Though it was not until after Fitzgerald’s death that Schulberg would learn the novel’s exact subject matter, he had long believed it was Hollywood, for Fitzgerald had barraged him with questions about the film industry and what it had been like growing up amidst it. Later, Schulberg was mildly disappointed to read in the first pages of The Last Tycoon an insight that he had given Fitzgerald during one of these interviews: the idea that Hollywood was an industry town like any other, except that it made movies instead of tires or steel. Yet it did not sting too badly. Reflected Schulberg, “I’ve known writers—I was raised with them—and I’ve known them from one end of my life to the other. And he was one of the gentlest, kindest, most sympathetic and generous writers I’ve ever met. At the same time, of course, he couldn’t stop lifting something you said because that’s the profession he was in.”

In late December of 1940, Schulberg, back in Hanover, had a drink with Dartmouth professor Herb West at the Hanover Inn. West “suddenly but terribly casually looked up from his glass and said, ‘Isn’t it too bad about Scott Fitzgerald?’” This was the first that Schulberg had heard of Fitzgerald’s death of a heart attack in Sheila Graham’s apartment. The obituaries would portray Fitzgerald as a mere mascot of the Jazz Age, a man unfit for the age of political commitment. Disgusted, Schulberg, John O’Hara, and Edmund Wilson, inter alia, approached The New Republic in 1941 with the idea of a Fitzgerald memorial issue, which was indeed run.

Schulberg’s novel The Disenchanted, published in 1950, was widely recognized as a roman-à-clef about his experiences with Fitzgerald, and it became a bestseller. It renewed interest in Fitzgerald and his novels, which were soon reprinted. Today, his critical reputation is unassailable.

This set piece to The Review’s Winter Carnival coverage, written by Nicholas S. Desai, has been reedited.