This past spring, in my first on-campus term at Dartmouth, I was afforded the opportunity of visiting the Rauner Special Collections Library, housed in stately, pillared Webster Hall. Over the course of three short visits, each limited to three hours due to COVID restrictions, I viewed a host of materials that the Library possesses in its archives.

I had first learned of Rauner’s stores of rare texts in a Comparative Literature course I took during the preceding fall term. As a cinephile, I was particularly excited to hear of Rauner’s Irving Thalberg Memorial Script Collection, an accumulated set of 2,481 screenplays from the Classic Hollywood era. Donated to the College with relative frequency from 1937 through the early 1950s, and sporadically thereafter through the 1960s, these screenplays were sent to the College in an effort spearheaded by film producer Walter Wanger ’15. Wanger also selected the name of the collection, resolving to honor the memory of the late MGM executive Thalberg (d. 1936), whom he considered to be “the greatest producer we ever had in the business.”

An independent, socially conscious, and altogether intellectual film producer, Wanger held a strong belief that the motion-picture industry was in need, above all else, of young writers who understood how to compose effective screenplays. He was, moreover, especially eager that his alma mater should offer this kind of instruction. Accordingly, by early 1937 he had begun to discuss with then-President Ernest Martin Hopkins and English Department Chair W. Benfield Pressey the possibility of instituting a course in screenwriting at Dartmouth. Responding positively, these men expressed their enthusiasm and willingness to create such a course but noted that professors and students would need scripts to study. Wanger replied that he understood their concern, and he promised to furnish the College with all of the scripts it could ever possibly need for the new course. And so he did.

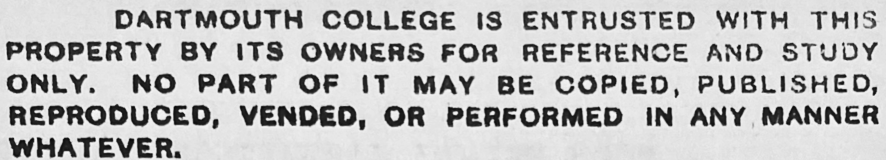

[S]cripts were collected by Mr. Wanger from the “Hays Office,” the Producers’ Association censorship office. To get them, the Trustees of the College deposited with the legal department of each producing company an agreement, still in effect so far as I know, that ownership of the scripts remained with the producer, that the scripts would be used only in instruction, that no copying or quotation or any form of production be permitted. The substance of the agreement was to be stamped on each script.W. Benfield Pressey

Willard Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory, Emeritus

13 October 1965

as seen on scripts in the Thalberg Collection

In addition to forwarding scripts he retrieved from the Hays Office, Wanger was successful in lobbying studios and friends to do so as well. However, not all of the scripts received by Dartmouth were censor-reviewed drafts from the Hays Office. For instance, when Wanger wished to send the screenplays for his own films, he would often dispatch personal copies of shooting scripts. Wanger’s good friend, the producer David O. Selznick, did the same. One of Selznick’s most notable donations to the Thalberg Collection was a shooting script for his production of Gone With the Wind (1939). A review of this script not only reveals penciled-in annotations of production dates but also demonstrates Selznick’s indecision as to how the film should end, even as it was in production—the screenplay contains three different scripted endings.

Intriguingly, not all of the collection’s scripts are contemporaneous to the year in which they were sent to Dartmouth. Labels suggest that when Wanger’s effort began in 1937, a supportive E.J. “Eddie” Mannix, MGM’s general manager and notorious “fixer” of stars’ indiscretions, saw fit to forward to Dartmouth various filed-away screenplays of notable MGM films from the preceding years. It would appear that Mannix sent screenplays for famous productions including: The Thin Man (1933), Treasure Island (1934), The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1934), Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), and A Tale of Two Cities (1935).

Armed with screenplays sent by Wanger, Selznick, Mannix, and others, Dartmouth’s instruction in screenwriting began in the 1937-38 academic year as an optional segment of upperclassmen’s writing courses. Any interested students were given scripts to study and were assisted in attempting to compose their own. Instruction in this manner was apparently sufficiently successful and popular to merit the formation, as was originally planned, of a separate upper-level course in screenwriting. This course began in the second semester of the 1938-39 academic year, marking the return to Dartmouth of the chair of the English Department, Professor Pressey, from some eight months spent with Wanger in Hollywood studying filmmaking and screenwriting techniques. It was Pressey who thus served as the instructor of the course, entitled “Writing for the Motion Pictures,” in which capacity he would remain until its cessation in 1953.

Pressey later commented that the course came to an end after it had fallen out of favor with then-Dean of the Faculty Donald H. Morrison. Ultimately, said Pressey, Morrison would not allow another instructor to assume responsibility for the course once Pressey, nearing retirement, decided to bow out of teaching it in any additional terms. The precise reasons for the dean’s apparent lack of enthusiasm for the course remain unclear. It is doubtful, for instance, that interest among students had been dying out, given their manifest interest in film studies just several years later in the early 1960s (of which interest the Dartmouth Film Society was born). Regardless, what is clear is that the College continued to be sent screenplays through the 1960s, suggesting that donors recognized the historical importance of preserving these scripts. Indeed, while originally intended to enable the study of screenwriting techniques, these many Thalberg Collection scripts today constitute nothing short of invaluable artifacts, as useful to film historians and researchers as they once were to prospective screenwriters.

An analysis of the scripts in the collection yields some fascinating insights. Although by and large each of these screenplays asserts the status of “Final Script,” it is well documented that the drafts sent by studios to the Hays Office were often submitted solely with the intent of obtaining approval. To this end, once a Seal of Approval was issued to a film on the basis of its submitted script, it was not uncommon for production staff to engage in rewriting of some consequence. Thus, there often exist differences between many celebrated films as we have long known them and their screenplay drafts held in Rauner—fascinating material for film aficionados to scrutinize. There are also many amusing annotations by censors from the Hays Office to be found on these scripts. For instance, on the script for The Maltese Falcon (1941), one can see repeated scribbles dictating (and warning, lest cuts be decreed) that Peter Lorre portray his character, Joel Cairo, in purely masculine fashion. True to form, Lorre ignored and subverted the censors’ decree, as can be seen in the final film.

Also of note is the absence of certain films from the current collection. A 1965 index of the Thalberg Collection makes reference to a screenplay for Orson Welles’ legendary Citizen Kane (1941) in its possession. Sadly, the collection’s script for this film, widely held as perhaps the greatest ever made, has long since been missing. Likewise, it is known that the collection’s screenplay for Howard Hawks’ acclaimed The Big Sleep (1945/46) has unfortunately been missing since at least 1978.

As a final point of history, Walter Wanger was a very successful and well-regarded (if uneven) producer. His diverse efforts—screenplays for all of which through 1953 can be found in the Thalberg Collection—included masterworks such as John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939) and Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent (1940), several Fritz Lang films, and an array of strong and remarkably literate low budgeters of historical, science fiction, and even exploitation varieties. He also produced several poorly received financial disasters, most notably the sluggish and bloated Joan of Arc (1948) and the overlong, overwrought Cleopatra (1961), which all but bankrupted Twentieth Century-Fox. Still, his reputation for high-quality filmmaking remains strong to this day, and we can be thankful that his devotion to his alma mater has enabled Dartmouth to possess a screenplay collection of substantial historical importance.

Be the first to comment on "Gems of a Bygone Era: Rauner’s Classic Film Script Collection"