When studying history, it is all too easy to think that the course of human events was inevitable. From geography in Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel to minute institutional differences in Acemoglu’s Why Nations Fail, one need not look far in the modern historical literature to find one of the many books which argue that irresistible fundamental forces pushed humanity towards an almost predetermined end result. Yet, this submission to historical determinism is not universal. No, some hold that individuals can have a significant effect on history, perhaps by re-directing those underlying currents that to others seem so overpowering. In Gallop Toward the Sun, Dartmouth alumnus Peter Stark ’76 argues that a few crucial years in the early 19th century and the actions of a few great men determined the course of American expansion and the destiny of the continent.

Stark’s book revolves around the duel between two giants of early 19th-century America. On one side was the famed American Indian hero Tecumseh, a noble leader who created a coalition of Native tribes in opposition to American expansion. On the other side was American general and future president-for-a-month William Henry Harrison, an ambitious man seeking personal glory. Stark shows how the two men’s lives converged as the United States pushed farther into the Midwest, and he depicts their eventual conflict as Tecumseh’s Native coalition clashed with an America keen on pursuing manifest destiny. However, in telling a story of two polar opposites, Stark leaves no room for nuance in the characters of the two men. Moreover, in considering this grand conflict as a contest between two men, Stark gives perhaps too much credence to the idea that a few events or two individuals can totally change the course of history.

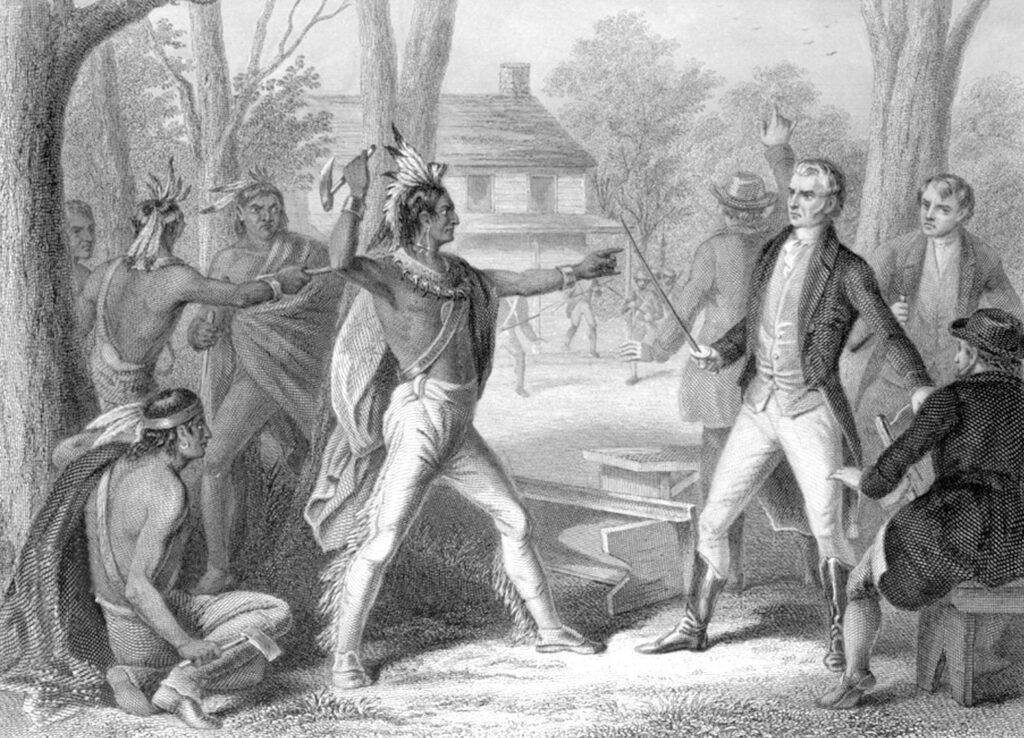

The book begins on the cusp of the War of 1812, during peace negotiations between Tecumseh and Harrison in a grove near the general’s grand estate, a piece of the American south transported to the then-undeveloped wilderness of the Indiana territory. From this first scene, Stark praises Tecumseh and creates for the reader the impression of an almost perfect leader. Stark relates firsthand accounts from the meeting which attest to Tecumseh’s inspiring presence and almost magnetic charisma. While also attributing some of these qualities to Harrison, Stark from the very beginning clearly considers Tecumseh to be a superior leader, and quite frankly a better person. This difference in portrayal continues as the book jumps back in time to relay the origins of the two men.

William Henry Harrison was a scion of the Virginia elite, the youngest child of Benjamin Harrison V, signatory of the Declaration of Independence and founding father. After Benjamin’s death, young William was placed in the care and tutelage of Robert Morris, a wealthy merchant and financier of the Revolution. From there Harrison spent several years looking for a path to reach the political heights for which he believed he was destined. Seeing opportunities in the West, Harrison joined the newly reformed American military as an officer, and he took part in expeditions against the Native Americans throughout the 1790s.

Tecumseh, in Stark’s narrative, was by contrast born into more harsh, if not humble, circumstances. His father was a Shawnee warchief, and Tecumseh spent much of his early life relocating to avoid American attacks during the Revolutionary War. Stark emphasizes Tecumseh’s natural aptitude for leadership, evident from an early age, and absence of vanity or desire for self-aggrandizement. He goes into extensive detail on the way of life that was central to Tecumseh’s tribe. Learning to survive in the wilderness from a young age fostered individual ability, while adherence to tribal customs ingrained a deep loyalty to tradition. Tecumseh quickly became a prominent Shawnee warchief, famed for his personal bravery. Stark contrasts Tecumseh’s desire to protect his people with Harrison’s embrace of the idea of manifest destiny to propel his own career. To Stark, Tecumseh is a true hero, while Harrison was a base opportunist. While acknowledging Harrison’s own bravery and ambition, he characterizes the general as vain and self-serving. Stark further details Harrison’s prejudice against Native Americans and his life-long support of slavery.

The core of the book is devoted to decades-long grappling between the Native tribes and the US government in the Midwest, personified in the rivalry between Tecumseh and Harrison. In the leadup to their first confrontation, white settlers pushed west into Ohio, destroying several Native villages and provoking retaliatory violence from Native inhabitants. White settlement necessitated land acquisition, and various American authorities attempted to force on tribes treaties that would strip them of their land. The tribes took up arms against this encroachment, and they won several victories against American forces, before facing the American army at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. It was here that Harrison and Tecumseh would first clash, though indirectly, as each served under his respective commander. The US won that battle, forcing the Treaty of Greenville upon the Native Americans. The treaty granted much of Ohio and parts of Indiana to the US, and it ended the first wave of resistance to American expansion.

However, a select group of Native leaders refused to sign this treaty. Tecumseh was among them, and he gained notoriety for his opposition to further concessions to the US. In the years after Fallen Timbers, he formed a coalition of Native tribes to resist further encroachment. His brother, commonly known as the prophet, led a religious movement calling for a return to traditional ways of life, while Tecumseh spent years on diplomatic missions up and down the Mississippi, rallying one tribe after another to his cause.

For his part, Harrison rose further through the ranks, eventually being made governor of the newly carved-out Indiana territory in 1801. As governor, he sought to take still more Native land, playing tribes against one another in order to secure unequal treaties. In Stark’s telling of it, Harrison quickly abandoned Jefferson’s plan of “civilizing” the Indian to focus on simply removing him from all lands which America desired. Stark explains that Harrison, seeking a political career in Washington, needed the Indiana territory to reach a population of 60,000 white settlers and become a state. It could then elect him Senator and send him to D.C. News of a charismatic figure unifying tribes soon reached Harrison, and he redoubled his expansionist efforts so as to not give this nascent tribal confederacy any breathing room.

Harrison’s largest land grab came in 1809 with the treaty of Fort Wayne. The treaty, brokered with much cajoling and personal bribery of corrupt so-called “government chiefs,” acquired nearly 30 million acres of land in Illinois and Indiana for the US. It also proved to Tecumseh that the United States could not be accommodated. Peace negotiations failed, and Harrison attacked Prophetstown, a settlement established by Tecumseh’s brother. The battle of Tippecanoe, named after the river near which the settlement sat, made Harrison’s reputation. While Stark criticizes Harrison’s conduct of the battle, notably his decision to leave fires burning in camp which illuminated his forces to the Native warriors hiding in the forest, he does credit Harrison’s personal bravery. Importantly, the battle ensured that Tecumseh, not his brother, would be the foremost leader of the Native confederation. He was himself not at the battle, but he used the attack as a rallying cry to draw yet more tribes to his banner.

Aware of mounting tensions between America and its mother country, Tecumseh allied his confederacy with Britain, hoping that with their weapons and men from Canada, he could retake lost territories up to and including Ohio. Harrison, under pressure from his superiors in Washington who wanted to avoid war with the Natives, decided that instead of reconsidering the treaty, he would inflame tensions so as to force the federal government to back him against his Native rival. Once war broke out between Britain and the US in 1812, Tecumseh and his allied tribes quickly declared for Britain.

Stark credits Tecumseh with important victories, like the capture of Detroit. He lauds the warchief while at the same time blaming the British for their hesitancy. British General Proctor’s refusal to push into Indiana immediately after capturing Detroit, which another historian might attribute to prudent caution, Stark decries as indecisiveness or even cowardice. Because of this inaction, Harrison was able to gather an army of Kentucky militia and Federal regulars, prompting the British to withdraw northward in the face of superior numbers. Stark in fact points to British hesitancy in attacking Fort Wayne as a critical moment. If Proctor had simply been bolder, he contends, the alliance could have taken the critical juncture and continued to advance, pushing the US back to “something approaching the size of the original Thirteen colonies.”

Tecumseh, unable to fight the Americans alone, followed the British. This withdrawal weakened the Native confederacy—despairing of victory, hundreds of warriors deserted Tecumseh’s cause. Harrison, emboldened by his superior numbers, recaptured Detroit and pursued Tecumseh and his British allies into Canada. At the Battle of the Thames, Harrison forced the British back before focusing on the Native contingent. In the ensuing battle, Tecumseh was killed, and with him ended any real unity among the tribes.

The central pursuit of the book—a comparison of Tecumseh and William Henry Harrison and a narrative of their struggle—is executed well, if with a clear bias towards the former. Stark aptly connects the two men’s early lives to their later endeavors, creating two cohesive pictures that develop as the book progresses. He employs a wealth of first-hand accounts of the two men, no mean feat in Tecumseh’s case given the scarcity of written records authored by Native Americans. Yet, readers interested in the two may want to read individual biographies of them to attain a more complete picture. As the book places the two men in opposition, it tends, perhaps inevitably, to depict them as opposites in every way. No room is left to even consider any idea that Harrison was motivated by any kind of patriotism or idealistic belief in manifest destiny. To Stark, ambition was his only driving force.

Conversely, Tecumseh is made almost divine in his selflessness and magnanimity. Certainly, Tecumseh accomplished wonders. His confederacy spanned thousands of miles, and it drew together tribes which had never before stood as one. However, no historical figure is without flaws, and Stark does not consider that Tecumseh could have had any. While individual failures are mentioned, like his flight from battle early in life, they are largely glossed over in the jump from one adulatory account to the next. Almost every first-hand description of Tecumseh’s greatness is taken at face value, while every statement made by Harrison is interpreted through the most cynical lens. Harrison’s support of slavery and his bigoted attitudes are emphasized, while Tecumseh’s inability to prevent his warriors from scalping surrendering enemy soldiers in his absence is explained away or forgiven. Tecumseh’s superiority as a leader of men is almost assumed. Tecumseh’s army largely melting away before the Battle of the Thames is glossed over, while Harrison’s ability to gather a larger force of volunteer militia even after a string of American defeats is chalked up to dogmatic rabble-rousing. Tecumseh was a more impressive and virtuous character, but neither he nor Harrison were so one-dimensional. Perhaps a consideration of each as an individual, instead of as one part of a good-versus-evil framework, could have painted a richer portrait of the two men.

Ultimately, Gallop Towards the Sun is more than a character study. It also hints at a vision of a future that could have been. In his book, Stark creates a dichotomy between two paths that America circa 1800 could have followed. On the one hand, there is the course of events that actually happened: America pushed west to the Pacific, destroying Native tribes or relegating them to small patches of land, reshaping the continent in its image. On the other hand, there is the dream of an America with a Native confederacy at its heart, united under Tecumseh’s rule. If such a confederacy endured, Stark posits that the United States could have been kept confined to the East Coast, creating a radically different and, in his mind, “better” outcome. While many readers will balk at this idea of a truncated United States, to others, including Stark, the possibility of a 19th century without the suffering that accompanied Western expansion is preferable. To Stark, this different history could have come about if but a few events had turned out differently—if Tecumseh, and not Harrison, had come out on top.

In departing from the idea that history is inevitable, Stark tends too far to the other extreme. He focuses almost exclusively on conflicts between individuals, and he ignores the broader forces that pushed America westward. Certainly, a Native victory in the War of 1812 would have slowed Westward expansion and may have even reversed it for a time. However, for his confederacy to have survived, for the American continent to be radically different today, Tecumseh would have had to hold back not just Harrison in 1812 but the tide of American settlers that poured continuously westward in the century after. Motivated by crowding in the Eastern states and immigration from Europe, factors which Stark does mention, millions of settlers would have flowed west with or without US government approval. Moreover, Tecumseh would have needed to maintain a confederation of diverse and disparate tribes, the goal of each of which was to maintain its own independence. To do this, he would have required constant British support and protection while also maintaining his independence from that famously imperial power.

Tecumseh, for all his vision and greatness as a leader, was molded by the millenia-old Shawnee way of life, even wedded to it. His revolution was, after all, a reaction to American encroachment. While in many ways idyllic, this non-industrial and semi-nomadic form of civilization simply could not have matched the rapidly developing and aggressive United States in purely material terms. Stark himself notes that Harrison was able to raise a larger force, from just Kentucky and Indiana, than Tecumseh’s confederacy could muster to defend its very existence. This disparity would have only grown, and Tecumseh’s confederacy would have fallen in the face of an aggressive, expansionist foe. The confederacy could very well have split apart after his death from old age, as it did in reality after his death in battle.

Throughout the book, Stark asserts that if Tecumseh had merely been born in another place and time, he would be remembered as one of the greatest leaders in history. But perhaps the fact that so great a leader was unable to alter the course of events is in itself proof of the impossibility of the task which lay before him. Moreover, in trying to show that Tecumseh could have altered history, Stark creates out of Tecumseh a superhuman figure, ignoring every flaw and failing that made him a man. Peter Stark’s Gallop Towards the Sun is a fundamentally optimistic book, perhaps too much so.

Be the first to comment on "Gen. William Henry Harrison, Tecumseh, and the Curse of History"