It is inconceivable to the modern American that World War II and the men who fought it would be forgotten. Rightfully so, they have been heralded as the Greatest Generation for their valiant defense of Democracy and their defeat of Nazism. D-Day has been immortalized in literature and film; George Patton is a household name, and the sight of Iwo Jima’s American flag is an enduring image. The war exposed the raw courage and character embedded in the American spirit. At least for this author, stories of our men in uniform excite emotion and pride. But, as these stories deserve (and need) to be told, so too do those of the forgotten. African Americans, unbeknown to most, did their part to secure an Allied victory. Their service, while ignored by the average history book, must be recognized.

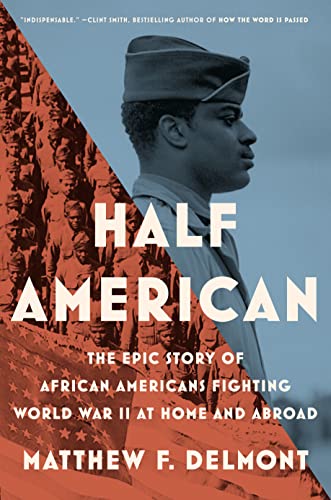

Dartmouth history professor Matthew Delmont’s Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad certainly does that. It is a study of African Americans serving overseas in combat, but also (and perhaps more so) about the struggles they faced at home. Delmont, to his credit, lets the history speak for itself. Save for the political conclusion, the pages are filled with firsthand accounts of oppression which, when weaved together with the progression of the Second World War, makes for an informative rather than accusatory experience. He enacts the eternal demand of students of history – just give us the history and we can reach our own conclusions.

World War II, of course, predates the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Jim Crow was as alive as ever: the South was segregated, African Americans had few opportunities to thrive, and as they faced the daily threat of lynching. Unfortunately, the situation was no better in the United States military. The armed forces, as Delmont points out, used a commissioned report from the 1920s as guiding policy: African Americans were deemed both mentally and morally inferior as combat personnel. As a result, African Americans were denied the ability to enlist, despite their desire to do so. Even after activism and internal realizations opened it up to more black people, they were mostly relegated to labor and transport battalions. Racial prejudice, no doubt, disadvantaged U.S. armed forces on the battlefield. Delmont even details that some White soldiers preferred defeat over serving with African Americans as equals. It was, in retrospect, a moral and practical nightmare.

Stories of hope and triumph are best found by looking at the brave men on the front lines. Half American includes an introduction to the famed Tuskegee Airmen, a famed group of Black American fighter pilots. Benjamin O. Davis, a Tuskegee leader, was a West Point graduate who, despite ambitions to fly, was assigned to teach at the Tuskegee Institute as the Army Air Corps did not accept African Americans. In 1941, however, political pressure prompted President Franklin D. Roosevelt to expand African American opportunities, and Davis was sent to fighter pilot training, where he excelled. His 99th Fighter Squadron deployed in the spring of 1943 as part of Operation Corkscrew where they fought against the German forces over the island of Pantelleria. It was the first time African American pilots saw combat in the U.S. Army. The airmen’s success proved their abilities to military leadership and helped advance racial integration. At sea, the Merchant Marine had already been racially integrated and offered African Americans the opportunity to serve. Captain Hugh Mulzac, at the helm of the multiracial cargo ship SS Booker T. Washington, made dozens of trips across the Atlantic and Pacific. His success in transporting hundreds of troops and thousands of pounds of cargo opened the door to other African American captains. Davis, Mulzac, and other trailblazers contributed to the war effort. Perhaps more importantly, they broke barriers for future servicemen.

The book, as a survey of 1940s racial activism, sets a good background for the more well-known Civil Rights Movement. Early equality leaders like A. Phillip Randolph and Walter White lobbied the federal government, and at times secured meetings with President Roosevelt to accord more just treatment for Black Americans. Randolph’s impressive organization threatened a massive protest—one that would frighten Roosevelt and lead to his signing of Executive Order 8802, which banned labor discrimination in defense industries (the policy was hardly enforced, but was nevertheless a win for the movement). African Americans also achieved advisory positions under Secretary of War Henry Stimson and despite rampant segregation and prejudice, still made progress in procuring social change. A recurrent cast member of Delmont’s story is NAACP attorney—and future Supreme Court Justice—Thurgood Marshall. Before he was assigned to protect the Constitution in Washington, he was on the ground, traveling from one injustice to another to ensure legal equality. Marshall litigated against segregation case by case, his efforts culminating in the famous Brown v. Board of Education decision. Before that, though, he undertook legal work to prevent unfair treatment of African Americans in court-martials. Delmont offers insights into the Civil Rights trailblazer’s lesser-known yet equally-important early career; Half American puts the 1960s into greater perspective.

Half American uncovers certain events that force the reader to question why they have never encountered them before. In July of 1944, an explosion at Port Chicago near San Francisco, California killed three hundred and twenty people, including two hundred and two African American sailors. The disaster, which top military brass attributed to inferior black skills, was actually the result of poor explosives training and safety afforded to the sailors. The seamen protested the dangerous conditions and refused to load bombs until improvements were made but in doing so were accused of and charged with mutiny. Their court-martial was the first mutiny trial of World War II and the largest mass-trial in the Navy’s history. Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP would offer their legal defense, but all fifty of the charged were found guilty and sent to a military prison. Thus, African American seamen would bear the responsibility for the Navy’s disaster. This account and the others like it in the book, as crucial and impactful pieces of history, should be better known to the average American. The journey to uncover hidden history is a righteous one. In today’s academia, books about race must be cautiously approached. Too often, readers are exposed to social justice contrition through which America is decried as systemically racist and the average white person as a bearer of privilege. The book though, to my commendation, was absent of any civil lecturing, and thus effective at cementing my preconceived belief that black WWII soldiers are American heroes. Despite the troubles they faced in their own country, they were willing to sacrifice their lives to protect it. It is comforting to realize the remarkable progress made in the latter half of the century towards America’s true ideals. One can acknowledge and learn from the ills of the past while at the same time appreciating the hopeful stories it produced and the good done since. Stories like these, too, ought not to replace the exultant history taught, but supplement it with the complete picture. Half American would make for a positive addition to one’s knowledge of both World War II and Civil Rights. It is, to be sure, a story worth telling.

I suggest giving a listen on YouTube to

“This Is Worth Fighting For”

by the Ink Spots (with WW2 footage).