The Dartmouth Twilight Song may seem one of the more cliché songs in the Dartmouth repertoire. It conjures images of Dartmouth men: bright-eyed, white-collared youths with neatly-parted hair and green sweaters. For those with keen ears and an affinity for the term social justice, it suggests an era when Dartmouth men strolled the campus singing quaint songs about Indians and puritanical values.

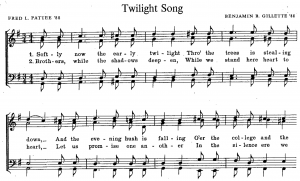

Penned by Fred Pattee and Benjamin Gillette, both members of the class of ’88 (1888), the Twilight Song has largely fallen out of favor thanks to its dated prose and classic melody. Franklin McDuffee ‘21’s Dartmouth Undying has replaced it in most repertoires, which is understandable considering its poetic verse and timeless air. The Twilight Song may be only a fading relic of a former Dartmouth, but it has not outlived its use or relevance.

Dartmouth seniors inevitably gain a new appreciation of our picturesque twilight. The hills pouring forth from the banks of the Connecticut are most dramatic when viewed from the Ledyard Bridge in the evening light. The fall foliage silhouetted against the white bricks of Dartmouth Hall is at its peak radiance as the sun sets. While most students only appreciate these things in fleeting moments, seniors become keenly aware that with the passing of each day, they draw closer to the twilight of their Dartmouth days. The Twilight Song emphasizes both the beauty and inescapably ephemeral nature of Dartmouth and its twilights.

This nostalgia is not always positive. Far too often, Dartmouth students and alumni complain that the College is a shadow of what it once was. They point to declining rankings, rising admissions rates, and other meaningless changes in meaningless statistics. They cite negative press, a polarized campus climate, a grossly incompetent bureaucracy, and the lack of administrative vision. I do not dispute these latter trends, but the view that they represent a wholesale decline in the worth of Dartmouth College is profoundly ignorant.

Every period in every institution’s life brings with it this negative nostalgia. When Captain John Wheelock seceded from the College and helped found Dartmouth University, I am sure the students waxed poetic about Reverend Eleazar Wheelock’s iron-fisted rule. If you think DDS is bad, students literally starved in the early days of Dartmouth under Wheelock.

As Editor-in-Chief of The Dartmouth Review, I have been at the forefront of criticizing every aspect of Dartmouth. I have lambasted President Hanlon, criticized faculty, and debated countless peers. I have done all these things “for the sake of dear old Dartmouth;” sometimes you have to “shake the campus” and omit the “with her praise” in order to bring about positive change. I believe this is a fundamental difference between the nostalgia of the Twilight Song and that of today’s naysayers: the former cultivates positive values and the latter indiscriminately denigrates society.

People often criticize The Review for what they perceive as negative nostalgia. Our paper seemingly represents a wistful (or rowdy?) longing for “the good old days,” when Dartmouth embodied the spirit of New England aristocracy. I do not deny that we occasionally fall into this trap, but I do not believe this perception accurately represents what we stand for. At The Dartmouth Review, we work to understand both our current times and customs and those of “the good old days.” We sincerely advocate for the preservation of those customs that still hold value and the continuation of current trends that promise to improve our society.

Many critiques of Dartmouth’s culture focus on its loss of “grit.” There is a prevailing sense that Dartmouth men of old spent all their time skiing, spontaneously singing drinking songs, carving senior canes, attending daily formal fraternity dinners, and engaging in elaborate hazing rituals. Those who lament “Harvardization” often refer the loss of to such customs amid efforts to increase the College’s academic standing. What they do not realize is that students made time for this gentlemanly life by making room on their transcripts for the infamous “gentlemen’s C.”

Academics at Old Dartmouth followed a traditional liberal arts model with a strict core curriculum and few elective courses. Classes followed more traditional formats, and grades were of secondary importance. Students held significant power over their professors, exemplified by the practice of harassing professors in their homes with loud horns at night. Selective admissions, the G.I. Bill, and the admission of women all increased academic rigor at Dartmouth. These changes to the Dartmouth of “the good ole days” ensured that better and more competitive students populated the college.

At The Review, we do our best to praise and advance Dartmouth’s current academic standards, but we also seek to restore some of the grit that made Dartmouth unique. G. K. Chesterton once wrote, “Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to that arrogant oligarchy who merely happen to be walking around.” We concur and believe that both tradition and progress have a rightful place in our society.

The Twilight Song is not a cliché hangover from Old Dartmouth; it is a relevant reminder of our values and the fleeting role we play in the history of this great institution. As the shadow of graduation looms, Dartmouth students have an obligation to temper our sadness by ensuring that future classes have their share of “happy, happy days.” In the wide world as at Dartmouth, we must remember to remain objective in our undertakings and true to our values.

Be the first to comment on "Happy, Happy Days"