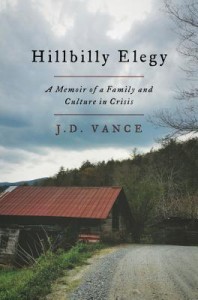

Scrolling through post-election headlines, it is nearly impossible not to find countless think-pieces written by the left-leaning (or in some cases, right-leaning) media dedicated to explaining Donald Trump’s victory by the grace of the “white working-class.” While some articles address the dark side of globalization and a general sense of decline, others condemn white Americans living in the Rust Belt as racists emboldened by President-Elect Trump’s pledges for increased border security and a refreshing disregard for suffocatingly strict political correctness. Yet despite analysts’ best intentions, their emphasis on the economic superstructure driving working-class whites to support Donald Trump might be shallow analysis, or so asserts JD Vance in his book “Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis.”

Vance, the fatherless hillbilly with an addicted mother turned Yale Law School graduate and National Review contributor, recalls his endless slew of father figures, a domestic life rife with verbal and occasionally physical abuse, and ultimately how he found success with the help of familial stability. Vance’s anecdotal style is full of dark humor and amusing tales of hillbilly America. At one point he recalls his gun-toting grandmother, “Mamaw” serving his drunk grandfather, “Papaw,” trash, and later dousing him with gasoline after he failed to live up to her ultimatum of giving up alcohol. While some readers may laugh at Vance’s stories, beneath these vignettes are the incredibly negative effects of such chaotic domestic life on children. His mother, the most controversial figure in his life, suffered from an abusive household and a teenage pregnancy; enough to set any child behind. Yet “Aunt Wee,” his mother’s sister, was able to escape such a life despite the same circumstances. The successes and failures of himself and his family members take a central role, but he also brings in statistics to expand on his experiences.

Vance’s harshest observations stem from the hypocrisy he saw in his community. Hillbillies profess their religiosity but do not attend church, rail against “welfare queens” while speaking on their government-bought cell phone, and maintain a fierce and sometimes violent loyalty to family without fixing domestic turmoil that drains upward mobility from their households. Exploring these inconvenient truths is what lays at the heart of Vance’s conservatism, and is perhaps the root cause of the Rust Belt flipping from loyal union Democratic voters to Republicans quickly. Vance recalls the injustice he felt as a teenager working as a cashier at a supermarket witnessing customers gaming the welfare system before turning around and lamenting freeloaders taking from the system. The lack of self-awareness, or denial, is remarkable.

The problems Vance exposes are cultural. Perhaps government assistance keeps many members of his community from destitution, but the issues raised in “Hillbilly Elegy” condemn the welfare state in its current form. It’s not temporary. And it’s not a viable option in fixing the problems of the white underclass. Vance’s prognosis follows from the cultural issues at the heart of these woes. His own miracle was rooted in the power family. Early on in high school, Vance was failing; not because he was dumb, but due to his incredibly dissonant domestic life. Vance credits his remarkable turnaround to his hardened hillbilly grandmother: Mamaw. While his domestic life was still unorthodox, Vance was in an environment that provided both encouragement and stability. Given this, he was able to enroll at Ohio State University, but not before taking a crucial detour.

Another focal point in Vance’s memoir is the power of the military in building maturity, responsibility, and confidence. Deferring his acceptance at Ohio State, Vance enlisted in the Marine Corps and served four years in public affairs. Learning leadership and earning the respect of his community are immediate benefits, but the value of his service proved to be far greater than he could’ve expected. He was taken care of: ordered to the infirmary when sick, supervised by a non-commissioned officer when buying his first car, and, and taught proper nutrition and fitness. In his own words, Vance felt invincible in college, a mentality that translated into graduating early with a double major Summa Cum Laude. Vance’s service in the Marine Corps marks a point in his memoir where his story becomes more unique and personalized as a result. Drawing fewer conclusions surrounding his personal experiences, he instead focuses on his observations: his culture shock at Yale, navigating new social faux pas around elite lawyers, and falling in love with his eventual wife. The Marines gave him much maturity, but he does not touch the subject of declining national service in America. Similarly, Vance recalls struggling socializing with classmates inculcated in upper-class rituals, yet does not assess the effects of networking or connections that may leave the underprivileged out.

In the latest election, both major candidates focused on job creation in America’s Rust Belt. President-elect Trump endorsed tariffs and a crackdown on Chinese currency manipulation while Secretary Clinton proposed killing the coal industry while installing clean power jobs directly in the Rust Belt. “Hillbilly Elegy” takes the conversation in a different direction. While Vance acknowledges that economic success would help, he believes the problem goes deeper than money. Instead, he recalls somewhat of an aversion to hard work. When working a well-paying job at a tile company before law school, Vance remembered a man fresh out of high school with a pregnant wife. Even with every incentive to provide for his family, the man would miss at least one day a week and disappear for hours when he was working. When the man was finally fired, he exploded at his boss, seeming to take no responsibility for his actions.

Vance benefits from his status as a cultural insider not seeking election. He can diagnose his community’s problems from within and hold a mirror to hypocrisy. Vance’s memoir holds a candle to the plight of hillbillies: perhaps the only group in America that one may scorn as “trash” without earning social exile. Regardless of our ability to relate to his story, “Hillbilly Elegy” is a reminder that in an age of expecting more from our government, true change does not come from policy, but from cultural shifts starting at the most basic building block of our civilization: the family. Vance’s story and perspective endorse a more organic approach to problem-solving. The superstructure of our society can only impact us so much. No welfare check, school voucher, or food stamp can solve the breakdown of the family unit that plagued Vance’s community.

I am reminded of William Ernest Henley’s “Invictus” when reflecting on the messages of “Hillbilly Elegy”: “It matters not how straight the gate, how charged with punishments the scroll, I am the master of my fate, I am the captain of my soul.” Vance certainly does not ignore the disadvantages he and his community face, but his prognosis is rooted in American values. These values are perhaps best exemplified by the best of Appalachia: individual responsibility, a commitment to community, and above all the power of family. We must work to restore these values throughout the United States if we are to solve the issues plaguing our nation.

Thank you.

you forgot about the part where economics impacts values. The dysfunctional values preceded welfare benefis. The story is a good addition – it is one person’s story, not a macroeconomic study. I have read parts – I didn’t really see anything new to be honest. Maybe people reading the book, live in a bubble.