It is natural for college students to develop a sincere attachment to the mail. For a significant majority, their respective freshman years represent their first experiences living apart from the homes and families in which they were raised; an institution which has the potential to serve as both a tether to familiar people and a source of parcels containing forgotten necessities will thus be embraced with enthusiasm. At Dartmouth, the natural tendency to seek connections to home through mail plays out with greater intensity because Hanover is an unfamiliar environment for many students (only about one in five of whom hail from New England), and Dartmouth’s rural setting necessitates the procurement of specialty items through online shopping.

As a result, students will quickly find themselves extremely well-acclimated to the process of receiving mail through the Hinman Mail Center. Disappearing beneath FOCO on a regular basis is a fixture of many students’ routines at the College from Orientation to Commencement. While Hinman’s specific implementation is unique to Dartmouth, mailrooms bearing many of its key characteristics can be found in every one of Dartmouth’s peer institutions. Despite this, having a formal mailroom is a relatively recent development in the College’s 256-year history.

Originally, there was no need for a mailroom because the College’s smaller undergraduate population made quotidian delivery to individual rooms feasible. Postmen brought parcels to students directly and they deposited letter mail into rooms through the mail slots formerly present in each student’s door. As impractical as this would be to reimplement today, this remains the single most convenient system which has been employed in Dartmouth’s history from the perspective of a student. Many residence halls in current use which have not seen major renovations since that era retain vestiges of mail slots long since rendered inoperable. The overwhelming majority of mail slots in Lord Hall, Streeter Hall, Richardson Hall, Woodward Hall, South Massachusetts Hall, and Butterfield Hall remain, and there are a handful which can be spotted in Gile Hall, Ripley Hall, Smith Hall, and Topliff Hall.

The common thread which connects those dormitories is their construction before the Second World War. Around the time of America’s entry, the chain of events which culminated in our present Hinman was set into motion. An effort to increase the efficiency with which the Hanover Post Office operated brought about the end of delivery to individual rooms and the installation of pigeon-hole mailboxes within each dormitory. Each room would be assigned a box into which its mail would be placed close to the entrance of the building. While the war ended in a few years’ time, this system for disseminating mail would remain in place for multiple decades.

The dormitory mailboxes significantly reduced the complexity of the postmen’s routes, but they brought about certain issues. Certainly the students were displeased with the loss of the convenience of room delivery. Many students took issue with the fact that the mailboxes were completely insecure; of particular note is the frequency with which magazines would be stolen. Students’ eagerness to receive their mail often led to the descent of unruly mobs on the boxes following the postman’s departure. Most troubling to the Administration, the continued involvement of the Hanover Post Office meant that postage for written communication between College departments and students was becoming an increasingly significant expense.

An opportunity to take control of the distribution of mail presented itself when Dartmouth built the Hopkins Center for the Arts. The inclusion of Dartmouth’s new mailroom there was partly practical – the Hop was a major structure already under construction – but partly inspired by a desire to bring students who otherwise would be somewhat hesitant to engage with the arts into the building on a regular basis. That reasoning helped convince Lloyd Noland ’39, a man who was significantly involved with the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, to donate a sizable sum in honor of his father’s best friend and the namesake for the system, Herbert Hinman ’07.

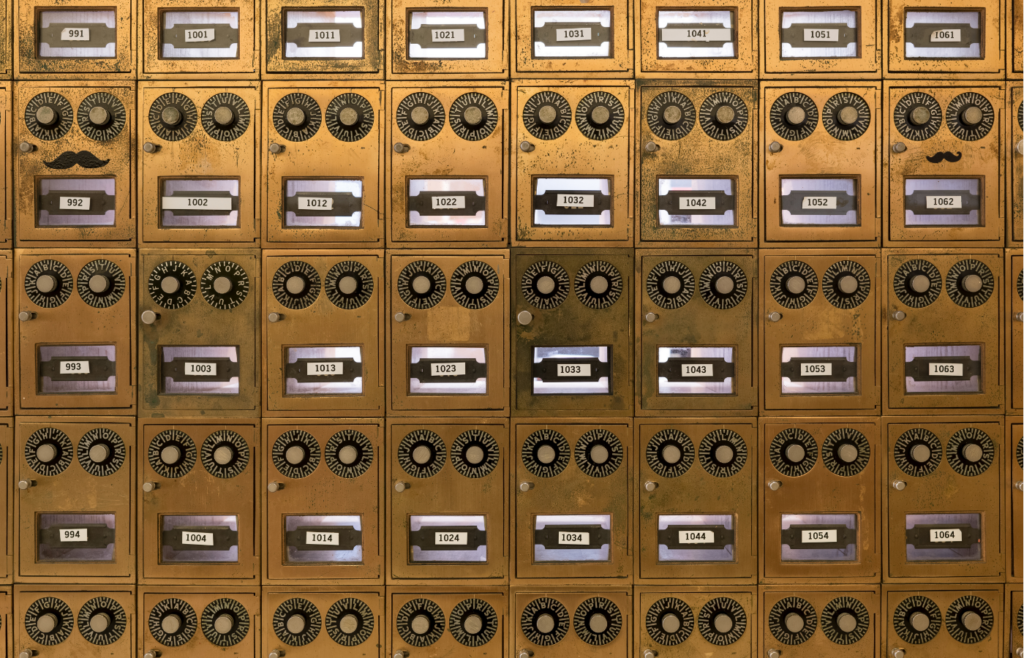

When the “Hinman Post Office” first opened in November 1962, students began receiving their letter mail from assigned, numbered boxes. The Hinman contained walls covered in metallic doors which guarded students’ mail behind combination locks. The sides opposite the doors were left open to face the sorting room. Ultimately, the practical experience of receiving mail was as if the students’ pigeonholes were simply moved to the Hop behind locks: boxes were still linked to rooms (not students), and they were shared with roommates. Taking mail delivery out of the dormitories entirely was even more inconvenient for students, but students, professors, and administrators alike could now send postage-free mail to one another. Additionally, parcels continued to be delivered to dormitories (as they had been before).

The next round of major changes took place in September 1972. Students lost the ability to receive packages within their dormitories since Hinman introduced a counter at which students would queue for the receipt of Parcel Post. In doing so, a precursor of the system which currently governs all mail at Hinman was introduced.

At the same time, significantly more mailboxes were constructed to allow students to be assigned personal boxes retained for the duration of instruction at Dartmouth. This was done to alleviate anticipated confusion due to the frequency with which students’ mailing addresses would change if the old system were retained alongside the D-Plan.

However, the fact that this new system coincided with the beginning of coeducation led to a clumsy implementation: Dartmouth classes were growing in size at a rate Hinman was not prepared to manage. For three consecutive years in the 70s (1975-1977), there was an insufficient number of Hinman boxes to greet the incoming freshman class, which prompted an improvised version of the box-sharing aside.

This system, with boxes for letters and the counter for parcels, largely remained intact over the course of the succeeding decades. In 2012 an expansion prepared Hinman to accommodate more parcels. In 2017, students became able to mail packages directly from Hinman rather than the post office. However, the recent renovations to the Hop sent the mailroom into the basement of FOCO on January 3, 2023, where it remains to this day.

The decision to sell the doors from the old Hinman boxes makes it evident that this move is intended to be permanent. Since they have been shipping to nostalgic alumni since late January of this year, the original Hinman can never again be fully reassembled. The fact that the alumni are willing to pay in excess of a hundred dollars for them reveals something about the difference in charm between the two locations: it is difficult to imagine forming that degree of emotional attachment to any element of the current location.

The new Hinman requires that students queue even for letter mail in the same way they would for parcels at the Hop. This has the effect of making it significantly more difficult for a trusted individual to pick up his friend’s mail, and it also increases wait times by forcing those expecting letter mail into the general queue. FOCO is likely a more convenient location for many of the students, but it both means that (as unlikely as it was) it is essentially impossible to see a return of the Hovey Murals and that Hinman is no longer serving the purpose of bringing students into unplanned contact with the arts.

In its present location, its hours (8AM – 4:30 PM, Monday through Friday) often cause difficulties for students in planning to visit before it closes. Its closure during the weekend leads to a buildup of parcels; dispensing of three days of mail on Monday often produces especially long queues. Those hours are the product of years of slowly cutting back: prior to February 1980, Hinman was even fully open on Saturdays.

On a campus which has voraciously embraced email, intra-campus mail is hardly the central focus it once was. If a student has occasion to use it now, however, it operates with tremendous speed and efficiency: if an unstamped letter is handed to a worker at the “shipping” window, it will immediately be filed with the recipient’s mail in under two minutes.

The workers are generally quite impressively efficient given the sheer volume of mail which passes through their care every day. Taking the average of measurements from different days of the week and different times of the day, as long as there are two workers in the receiving window a given student’s wait will be 23.9 seconds per person ahead of him in the queue. This translates to an overall throughput of 150 people provided mail per hour. Hinman workers will respond to long queues by increasing the speed at which they work: the slowest times were all observed when 5 or fewer people were waiting.

Staff are additionally quite accommodating of larger parcels, even if they require certain complications in the process of picking up.

In general, the Hinman Mail Center runs relatively well and serves an important role in the lives of Dartmouth’s students, even if certain key decisions made at the administrative level have decreased the convenience of accessing mail over time.

Be the first to comment on "Hinman Through the Years"