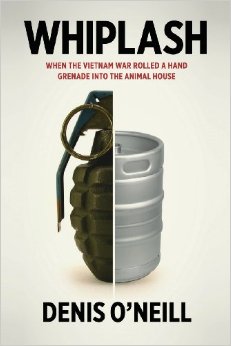

Whiplash: When the Vietnam War Rolled a Hand Grenade into the Animal House by Denis O’Neill (Vook, 330 pp.)

In what was undoubtedly the most influential game of their lives, the Dartmouth hockey team could barely keep their eyes on the puck. The game would be played, but their were no scouts to impress, nor a victory to be earned in the back of the net. This was one of the rare situations where the outcome of the game wouldn’t determine the winners. On the night of the 1969 Vietnam Draft, the hockey game was played with life and death hanging in the balance. In O’Neill’s words, “The real game that night was not on the ice.”

Intermingling competitive fun and deadly seriousness, Whiplash by Dennis O’Neill reflects on the timeless aspects of the Dartmouth experience. Beyond simply boozing with friends in fraternity basements, Whiplash captures the indescribable aura that coerced Daniel Webster to his famed quotation, “It’s a small college, but there are those who love it.”

On its surface, Whiplash is the story of a Chi Heorot brother during the Vietnam War. Specifically, it follows the lives of several brothers as their college experiences are transformed by seemingly unstoppable outside forces. O’Neill details their attempts to draft dodge, flavoring the story with insight into the lives of the brothers roaming “the Chi” from the Autumn of 1969 through the following year’s Spring. In doing so, Whiplash challenges strong values like tradition and the constant pressure for an ever-more-refined vision of a Dartmouth man.

The author empresses the lethal potency of war not only on his fraternity brothers but also on his readers through the tragic character, Birdy. Serving in the infantry in landmine-infested rice fields is a hellish predicament, code named “Mekong Delta,” and it contrasts starkly with the drunken shenanigans depicted in the surrounding chapters. By interspersing Birdy’s tale into three wrenching chapters, O’Neill ensures the realities of Vietnam are as laid bare for the reader as they were for students of the time.

Several of O’Neill’s focal topics of articulation have become ever-more relevant during this transitory and turbulent time for liberal arts campuses across the country. Operations like Moving Dartmouth Forward and the constant slough of protests motivated by racial and gender-based issues call into question the characteristics of an ideal Dartmouth student. Is he a champion for the voiceless or a politically-correct automaton capable only of espousing platitudes? Is he Dean Taymore or Phil Hanlon?

The author makes his feelings toward “the scourge” of political correctness known frequently: “this being a period of enlightenment in American education—a time when painted students with Mohawks could run around fires pretending to be Indians, and security at sporting events did not deter can of beer or bottles of tequila from being brought to the events—the men of Heorot were prepared to properly mourn or celebrate the twin competitions that lay before them: the game and the lottery. Win or lose, Dartmouth men knew the importance of the journey”

In the above passage and elsewhere, O’Neill provides the reader with a unique glimpse into the evolution of the Dartmouth Indian controversy with which most students are well acquainted. In the fall term just passed, Chi Heorot, alongside every fraternity, was informed that all depictions of the Indian must be scrubbed and marred from its walls. The disconnect between the Dartmouth described in Whiplash and the one we witness today is startling and disheartening. O’Neill leaves little doubt that the administration is the catalyst of these changes.

The most prominent member of the ‘69 administration detailed in Whiplash is Dean Taymore. Published in 2013, the same year as Hanlon claimed his zenith, it is difficult to lend credence to the notion that O’Neill designed his administrative powerhouse to draw an intentional contrast. Perhaps he had, in some form, insight into the personality of Phil Hanlon that would allow him to create such a starkly contrasting figurehead for the College. But such speculations are baseless, and it is more likely that Hanlon resembles the opposite of the powerful, passionate Taymore.

In O’Neill’s own words, “[Taymore] loved Dartmouth and most students viewed him as a fair-minded bridge between life in the undergraduate trenches and the administration. He was as comfortable playing beer pong in a fraternity basement as he was addressing the Board of Trustees.” With the force-feeding of MDF against widespread campus sentiment, Hanlon has ensured that any such bridge has since been burned. It is not easy to say whether the fire was first stoked by the students or the administration, but safe to say that small minorities from both ends soaked their half in gasoline as the stranded majorities watched in helpless dismay. With a hunched-over posture worthy of the slogan, “Just Endure,” Dartmouth students suffer against Hanlon’s MDF as they do with the New Hampshire cold; just another aspect of their penance.

Activism, then and now, offers the reader another firm handle for comparing the two Dartmouth’s we have before us. The embers of racially-stoked fires are still cooling in the midst of the disruptive Black Lives Matter protest that paraded through Baker-Berry Library just a few weeks before the end of Fall term. Eleven days after the incendiary event—which made national news, besmirching the reputation of the Black Lives Matter movement, both on campus and globally—President Hanlon was incensed, as can only be done by negative media attention, to respond to the incident. His e-mail, stuffed ad nauseam with platitudes and self-preservative language, offered only praise for the protesters and a distinction between their actions and the events that followed:

“This demonstration was a powerful expression of unity in support of social justice—Dartmouth at its strongest. I cannot say the same about events that transpired in Baker Library immediately afterward.”

Really, Phil? You can’t say the same? A racially inflamed group storms a study space on campus chanting “F*** your white tears!” and this half-acquittal is the most you can muster?

Hanlon’s unique ability to capitulate to these bullies parading for the ambiguous causes of social justice has diminished our school. He is not unique in his task of dealing with aggravated youth on a liberal arts campus. Over forty years before attaching “Occupy” to the man became a hip and socially commendable cause, Dartmouth students banded together in protest of the Vietnam War and the ongoing ROTC programs on campus, invading Parkhurst and expelling the administration.

Comparing the responses of Taymore and Hanlon forty-two years later offers insight into the source of the College’s modern affliction. In response to the students taking over Parkhurst in 1969, “Dean Taymore snapped. ‘Don’t touch me!’ he bellowed, grabbing the kid in a headlock. ‘Don’t you tell me what’s tolerable and what’s not! Don’t you tell me to go f*** myself!’ The Dean of the College had fifty pounds and eight inches on his opponent. Plus he was pissed off. He dragged the kid out of his office and into the lobby where dozens of other students shepherded other staffers to the door. Taymore burst into their midst like an incensed bull. ‘What are you doing!? This is Dartmouth!!!”

Some people might gloss over the use of a triple exclamation mark—perhaps more frequently seen in sorority response flitzes than a published memoir—but I feel they were included for a reason. The three punctuations represent the fiery passion that the Dartmouth administration of old distinctly had in abundance; a love for Dartmouth. Phil Hanlon’s frailty underscored, Taymore then sends in the police and the offending students are placed in jail for thirty days.

Although O’Neill depicts the protesters as brave activists fighting for their beliefs, he includes the incident alongside another violation. “She walked over to the window, lowered it and fastened the lock. She just stood there—as Danny had, hours earlier—each feeling as violated as the other. The next time Danny saw Julie, he was walking to class. He heard chants before he saw her in the middle of a hundred protesters.”

Just as Danny has broken a sacred trust, the Dartmouth students who expelled the administration from Parkhurst and nailed the windows shut violated the school. O’Neill has the foresight to see this unique play in student activism reoccurring once discovered: “It was one thing to oppose an unpopular foreign war; it was something else to physically seize college property and eject the President. It was radical in name, and in frequency. It had never happened before.”

The students that took control the second time around did not experience nearly as severe a punishment. And that’s a major point O’Neill makes in Whiplash. Activism needs to be difficult. It should be a grind to be aggravated because the struggle reveals who truly cares about the cause they support. “Occupying Parkhurst” was not brave the second time. It was safe.

O’Neill compares the Dartmouth experience to a road trip. It is clear that road trips were an integral part of his time at Dartmouth, but more than that, the author views his time at Dartmouth like the Green; a series of crosscutting paths to be explored and reformed when your destination changes. As students, we live a transient life. Our time here is four or five years in which we establish our lives, setting up camp like so many vagrants and wanderers. Dreams fall by the wayside and majors change as each person struggles to discover themselves. O’Neill embraces this period in which the destination is so uncertain: “If you keep your eyes looking down the road, the foreground will take care of itself.”

Existing at a college this small, there is a collective identity to which we all contribute. Students at Dartmouth face a unique identity struggle as they assimilate into our New Hampshire community nestled in the forest. Ubiquitous conversation topics seem to blanket campus like snow as the community lives in the present, in unison. We first experience this as freshman trips come to a close. Periodically, these waves of conversation wash over Dartmouth, Green Key, exams, other isolated incidents that vary from year to year. Maintaining an individual identity in the face of this conformity of experience is the plight of every Dartmouth student and the subject of much of O’Neill’s writing.

Ultimately, O’Neill illustrates a pure Dartmouth experience on the page. Quite unlike some other accounts of the Dartmouth experience, O’Neill manages to share a significant amount of his life in a fraternity in Hanover while still preserving the integrity of the institution. I eagerly await the opportunity to hear more of his experiences first hand, and envision the era before the administration decided to take the school on such a divergent pathway.

And maybe enjoy a beer or two.

Be the first to comment on "‘Nam and the Animal House"