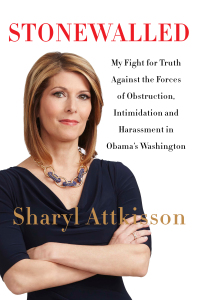

Stonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama’s Washington

Imagine, if you will, a world in which corporations and government officials squash press freedom and investigative reporting. One could assume that this is how authoritarian regimes would behave, nations (for example, Cuba or China) where whistleblowers tend to die of heart attacks caused by falling down twenty flights of stairs with a bullet wound in the temple. Former CBS journalist Sharyl Atkisson reveals in her new book, Stonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama’s Washington that this devolution of journalism is occurring in our own backyard–but rather than the violent crackdown in other nations, American journalists are being subtly smothered by an insidious combination of government pressures, corporate interests, and weak-willed news executives who kowtow to these coercive forces.

Atkisson’s saga begins with a chapter bluntly titled “Media Mojo Lost”–a discussion of disillusionment with authority early in her career as a local TV journalist in Vero Beach, Florida. One of her first stories involves uncovering the illegal dumping of raw sewage into local waters. Complaisant county officials denied its occurrence. Pressing on at the insistence of a whistleblower, Atkisson videotaped evidence of the pollution and the county’s complicity in its cover-up. She remarked, “The first time you catch the government in a lie, it changes you … This was at a time when I believed the government had to tell the truth … that they’d be kicked out of the government club [for lying to the press].” Another incident she uncovered was the Florida state government’s attempt to conceal an outbreak of citrus canker, which would lead to a quarantine on the lucrative orange industry. A direct inquiry to the state Agriculture Department led to a flat denial that is refuted by a visit to an afflicted grove, where she recorded state officials setting affected trees ablaze. A thirty-year track record of exposing deception among authority figures–tobacco companies claiming their products do not cause cancer; Enron claiming its finances were not fraudulent, for example–have cultivated in Atkisson a healthy mistrust of what established institutions provide to reporters at face value.

This skepticism towards authority has seldom been shared by news executives, who wring their hands over how stories will affect the carrot-and-stick incentives offered by government officials and advertisers. News companies are often financially influenced by larger corporations, which advertise or hold shares in them. Atkisson identifies one of her role models, Edward Murrow, who reported on the cancer risks of tobacco in the 1950s even as cigarette manufacturers pressured both CBS and advertiser Alcoa. These days, however, executives instinctively shy away from offending the powers-that-be. In one episode, a script written on an automobile company’s manufacturing defects gets a summons to the Washington bureau chief, who asks, “Why are we doing this story? … [The car company] says there’s not a problem.” Another story on the Red Cross’s disaster response has Atkisson summoned and compelled to show all of her notes, an unprecedented demand. Upon inquiry, the bureau chief reveals, “We must do nothing to upset our corporate partners [as instructed by higher-ups].” Another example: the White House punished C-SPAN (widely considered the Switzerland of news networks, famed for its neutrality) for what the Obama Administration considered unfavorable coverage. President Obama had mentioned in an interview, “We have not redecorated [the Oval Office] yet,” in solidarity with the recession-stricken American people. Despite demands from the White House press office, C-SPAN released the interview at the same time as a report from the Washington Post revealed that a multi-million-dollar renovation of the Oval Office would in fact be taking place. Since that day, the cable news network has been denied any interview with Mr. or Mrs. Obama.

With pushback coming from representatives of corporate public relations departments and government officials alike, today’s news managers preemptively select safe “day-of-air” topics (like the weather, British royals, and lost Malaysian jets) and even invite CEOs on air to peddle their wares; Atkisson brings up a report on March 21, 2012, when “CBS This Morning features a four-and-a-half minute interview with Taco Bell CEO Greg Creed … [who] is pushing Taco Bell’s ‘reinvention of the taco’ through the cross-promotional partnership with Doritos [a taco with a shell made of Dorito chips].” Farcically, this blatant product placement is picked up by other news outlets as “The New York Daily News, Time Newsfeed, Buzzfeed, Business Insider, Gawker, Daily Finance, and Huffington Post … [credit] CBS This Morning for being the first to ‘break’ the story.”

Criticizing this practice, Atkisson caustically notes how one would “ensure an automatic F on an assignment [at the University of Florida College of Journalism and Communications]. One was making a fact error. The other was by copying a story idea from the newspaper.” Yet, like the proverbial drunk searching for his wallet under the streetlamp (where the light is, not where he lost it), broadcast producers consistently look to what’s currently considered “news” by the New York Times, the Huffington Post, or by what’s trending on Twitter–not by what their investigative journalists are reporting from the field, reports that become pared down or rejected in concordance with executives’ biases. Atkisson expounds on how a story detailing billions of dollars’ worth of waste within the Department of Housing and Urban Development was derailed: the executive producer removed mention of exactly how much waste the Inspector General found; examples of where the money was wasted in Pennsylvania’s Hotel Sterling and in Louisiana; and soundbites critical of the waste. “All of those alterations in a story that ran under two minutes … In its final form, it seemed as if there were really no cause for major concern. It was a bland non-story that revealed little of interest. [My producer and I] found no sense in complaining. This was the new reality.” One could recall a joke told in the Soviet Union that reflected on similar changes to facts in news reports:

This is Armenian Radio; our listeners asked us: “Is it true that Akopian had won last Sunday a hundred thousand rubles in the state lottery?”

We’re answering: “Yes, it is true. Only it was not last Sunday but Monday. And it was not Akopian but Vagramian. And not in the state lottery but in checkers. And not hundred thousand but one hundred rubles. And not won but lost.”

The rest of Stonewalled revolves around Atkisson’s battles in delving into several episodes in recent history — Operation Fast and Furious; the waste of money on failed green energy companies like Solyndra; the September 11, 2012 attack on the Benghazi consulate; the farce of the Obamacare website rollout; the National Security Agency’s spying on American citizens. In each of these stories, Atkisson faced recurring setbacks: hostile bureaucrats, who attempt to browbeat her and the insipid executives at CBS into stopping her investigative reporting. She has felt the stages of this vicious cycle of obstruction before — PR officials attempt to find out what the reporters know, try to discredit them and controversialize whistleblowers, claim the truth is propaganda and spin, and after enough incontrovertible facts have been revealed, call the whole story “old news.” Atkisson has weathered such pressure in the past, but, as the title implies, it has gotten worse over the last six years. Attempts to get basic information has become a Herculean labor (analogous to cleaning out the Augean Stables), as our government’s PR officials seem to have an antagonistic relationship with reporters; Atkisson recalls trying to get information from White House press official Eric Schultz on Operation Fast and Furious, who eventually “erupts into a middle school meltdown. ‘Goddammit, Sharyl! The Washington Post is reasonable, the L. A. Times is reasonable, the New York Times is reasonable, you’re the only one who’s not reasonable!” Similar, if less explosive, obstruction from other departments in other stories consistently occurs, giving her a reputation for dogged persistence in pursuing leads.

Atkisson also finds her technology acting strangely–her telephone malfunctioning, her computers turning on in the middle of the night–and consultation with contacts at “three-letter agencies” reveals that she has become the target of federal wiretapping and hacking. News of this, along with revelations of the Justice Department’s subpoena of Associated Press telephone records, outrages many in the press but does not change the internal obstacles Atkisson faced in getting her investigative stories into the light of day, eventually leading to her resignation from CBS.

In the end, Atkisson has crafted a compelling string of stories about the pursuit of the truth in journalism. Stonewalled is an engaging book that provides an interesting flashback to the current events of the last few years. For those seeking deep analysis on the under-reported, obfuscated scandals of our troubled times, Sharyl Atkisson’s book will not be amiss.

Be the first to comment on "Operation: Stonewall"