Sing, Muse, of the rage of Branford Wentworth, ’20, the Little of Chad McCoy, ’18 the greatest fratstar of all the legendary Greeks, the social chair of Alpha Gamma fraternity, who sent so many Keystones down to Hades that they outnumbered the stars and whose dipspit was so vast and dark it blocked out the sun. Help me, goddess, to recount what I could not if I had a thousand tongues, of the twentieth year of the twentieth century, before the prophet’s curse, “No one will rage anymore,” came to pass, to tell of unspeakable terrors that visited upon the Phrygian citadels by the Greeks, of the Olympian administrators who dwell as gods on the high slopes of Mount Parkhurst, how great and powerful they, holding the terrible jugs of fortune and doling out happiness and social capital to some and to others, torment, probation and irrelevance. How I wish I had been born in another time, before the wickedness of this millennium and its twin infections of social media and sloppy, chaotic, over-righteous grandstanding overtook the glory of Old Dartmouth, as a noble beloved hound is overtaken and destroyed by fleas, and thus made the victim of lesser beasts.

Allow me this, O President Jupiter: that I may graduate swiftly before I live to see the utter demise of the great Greeks, and that though I be departed from these haunted shores, bare but for a lone, empty Grey Goose bottle sticking like the solitary gravestone of a forgotten civilization up out of the leaves behind FoCo, I plea that the story of my A-sideness will be told to generations upon generations, down to the fiery cataclysm that will erase all kings and countries.

It was 19S, and for years the gods had hurled increasing strictures upon the Greeks. Hazing, pledge term, single-gender houses, and tails with hard alcohol were all snatched from Webster as so many bleating lambs in the claws of a pterodactyl. In their place, with no consent asked or given: mandatory cameras, required student non-member residential advisers, prohibition of window coverings and door locks, and “diversity” requirements. With great strength the Greeks withstood these burdens and intrusions, knowing that it is not the place of humankind to war with god. And so, the many nations of the Greeks were slowly depleted of power, though they retained their place as the foremost social option for undergraduates.

The Greeks were always praised for their openness, their democracy and generosity to all. On a campus choked from the outside world by equal parts isolation, ice and Tartarine darkness, students were left like motherless puppies before the sharp gates of Boredom and Loneliness. The Greeks flung open their doors to the helpless, the ugly, and the uncool, as hospitality and guest-friendship numbered among the mightiest of Greek values, ushered them in from the cold and nursed them with free warm beer.

But thanks to the impositions thrown down upon them from heaven, those doors of love were now shut. Greeks looked powerlessly out of windows as scattered freshmen roamed the plains of Choates and McLaughlin and packed into tiny rooms to drink huge quantities of hard alcohol acquired and provided by young men whose virginities were well-kept secrets that they were extremely anxious to be rid of by any means necessary.

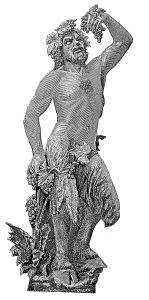

But soon, within the howling vacancy left by the leashing of the Greeks, a new power began to rise. It was a mysterious power that reared its head in the East (specifically at a large house past East Wheelock) a shifting cult of secrecy that had once been underground and little-mentioned, that rapidly swelled into a great colossus of darkness and tequila. This was Phrygian, a massive, independent secret society that operated off-campus and was swiftly attracting many new members to its breast, enticed by legends of gigantic, bizarre bacchanalia and queer rituals that occurred all safely outside the surveillance of the gods’ watchful eyes.

Pleased to see that students had at least somewhere to party, the Greeks accepted the situation and lived peacefully with Phrygian, separated by about a mile and the wine-dark Green.

That is, until an incident at a neutral party held at the track team’s off-campus house. There were mostly Greeks in attendance, including Nash A. Redford Jr. ’20, the president of Alpha Gamma, the most A-side house on campus on which the much-celebrated film Zoo Shack was based, and his brother Michael “Slick Mickey” Redford ’21, the president of Delta Xi, a similarly well-regarded fraternity. The party was celebrating the birthday of Joey Russell ’23, a freshman from New Canaan, who was then enjoying extreme social privilege since his older brother, Tim Russell ’20 was a high-ranking officer in Phrygian and his father Adam Russell ’85 had been a founding member.

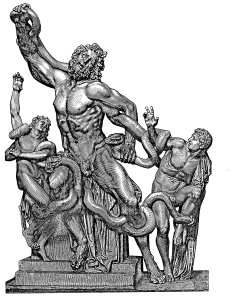

Joey, however, lured Helen Amaliano, ’22 up to room upstairs with the promise of lemon vodka shots and then attempted rather un-artfully to seduce her there. She refused him and headed straight downstairs to tell her boyfriend, who just happened to be Slick Mickey Redford, at which news he flew into a great rage, flipped a table and flung a few ill-chosen misogynistic epithets at Helen, who, currently drafting a thesis proposal on Sylvia Plath’s construction of “femality” in the Bell Jar, was not the type to look the other way at such language. After a minute of booting in the first floor bathroom, Slick Mickey emerged to discover that Joey had vanished from the party and Helen was nowhere to be found. She had, as it turned out, left with Joey to anger Michael in retaliation, a tactic that she soon regretted but stuck to anyway, despite Joey’s constant attitude of pissy entitlement and an irritating habit of turning every conversation about her emotions into a conversation about his own.

The rather personal, private matter transformed into one of universal publicity however, on account of two things. First, Slick Mickey and Nash found out that in the week that followed, the Phrygian listserv had been awash with lewd gossip regarding the event, many of the details distorted to heighten the drama: “Mick walked in on Helen bonking Joey on the toilet seat!” or spiced up the weirdness: “He told her he wanted to glue googly-eyes to her back so he could make eye-contact with her at all time!” “She was holding a Winnie the Pooh doll in her teeth!” “They both kept screaming the names of finance firms the whole time!” and so on.

For these emails, which had been leaked by a rather more tangential affiliate of Phrygian to the pair of presidents, the society refused to apologize. But conflict was irrevocably aggravated the next day, when a rumor spread that Phrygian was planning to host a block party off-campus during Dreenky, the biggest party weekend of the term. Delta Xi, however, had always hosted a block party during that weekend, a party that was historically attended by thousands. When Phrygian announced their party, which was to be called “Cithaeron,” the rumor was confirmed and Delta Xi realized the severity of the threat, to not only its own relevance, but also that of the Greeks as a whole.

And so, Slick Mickey and Nash called together a meeting of the presidents of all the Greek houses, gathering in the basement of Delta Xi with all the cameras blacked out (“Fruit bats,” Mick would later explain to the inquiring security officer whose video feed had gone dark, “Fruit bats did it.”) Before they began to discuss the multi-fanged problem, they pushed all the tables together and played an epic game of Harbor using a thousand Orange Keystones, for each president had brought with him or her the greatest pong player from their house, including Brandon Wentworth ’20, the hardest brother at Alpha Gamma and the champion of Doming M@sters, a grotesque tournament he invented himself to accompany regular M@sters during his sophomore summer.

After every cup was sunk and drained, the Greeks stood before their empty ships and fell silent as Nash began to give his declaration of party war.

“The word fraternity, as you all know, is a combination of the Latin words ‘fratus,’ which means brother, and ‘Eternitas,’ which means eternity. We are our brothers’ keepers forever, not just in moments of blessedness, but even when all the gods of the earth and heavens have set themselves against us. This will be the last year that we stand by and worry, “Will this be the last year for the Greeks?” for this, this year, is that year. Our world, which is so ancient and beautiful and loved, will be gone before the Class of 2024 steps foot on our campus. Rather than live out this illness unto death, we are going to brand ourselves in the steel of frat history by throwing the sickest block party the earth has ever known, gods be damned! We will lose everything, our houses, our letters, our basement, our beer. But we will never lose our fraternity. That will survive in Dartmouth’s memory for all time. And while we’re at it, we’re going to blast Phrygian into deeper irrelevance than Milque and Cookies.”

This he spoke, and all present gave a great cheer, shotgunned PBRs and flipped on Kendrick Lamar. The men slaughtered fifty pigs and roasted them with smooth brews, sacrificing to Apollo, the head of GLOS, that he might be an ally and not a hindrance in their glorious cause. And thus, O Muse, began such an dreadful war, immortal in the minds of Dartmouth students thereafter, in which much was lost and much honor won, of heroes and fratstars, tragedy and betrayal, of booting and rallying. Sing, O Muse, of the rage.

Be the first to comment on "The Chilliad: Book I"