Barely twenty years before the College was founded, in the hazy mist of the early years of the Seven Years War, the British dispatched Major General Edward Braddock along with then-Virginia Colonel George Washington and thirteen hundred soldiers to check the advances of the French and to chase them out of North America. On July 9, 1755, Braddock, along with Washington and his army, crossed the Monongahela River in what is Pennsylvania today, hoping to attack Fort Duquesne, which was nearby and in the control of the French. The expedition was a disaster for the British, who lost a third of all their men that they entered the expedition with. Braddock died four days later, possibly shot in the lungs by a member of his own army.

In 1772, Rev. David McClure, who had been one of Wheelock’s students at the Moor’s Indian Charity School and one of the earliest members of Dartmouth’s faculty, made a missionary trip, which included the Monongahela River and the location of the battlefield. This area, which had been historically home to Native American tribes such as the Seneca, was part of McClure’s expedition. The remnants of the battle still marked the location, and visitors to the location often picked up mementos from the field, including bones and expired armament, well into the last decade of the eighteenth century. McClure, too, participated in this ex post facto collection of the spoils of war, bringing back two grapeshots. On the same trip, McClure met Lt. Jacob Fowler at Fort Pitt, Pennsylvania, on September 13, 1772. Fowler gifted McClure two tusk fragments and a molar, both from a Mastodon, an elephant-like mammal closely related to mammoth, that he had found near Big Bone Lick, Kentucky, where he was living at the time. McClure described the artefacts in a letter to Wheelock as “a few curious Elephants [’] Bones…for the young Museum at Dartmouth.”

On October 26, 1772, on his return to Hanover, Rev. McClure handed over his gifts to Wheelock, forming the core of what was originally intended to be a museum aiding in the study of the natural sciences and which transformed into one of the country’s oldest and largest collegiate collections of art and artefacts. The first piece of art that the College received was a silver Monteith made by Daniel Henchman and Nathaniel Hurd of Boston, a personal gift from made in 1772 by then New Hampshire’s Royal Governor and College Trustee John Wentworth and his friends to Wheelock, which was passed on to the collection in 1773.

Much of Dartmouth’s collections then lay scattered across various departments and their offices, and after 1794, these had been largely concentrated in Dartmouth Hall, which formed the physical core of the College. As Dartmouth prospered and round the girdled earth the Men of Dartmouth roamed, the College was able to acquire many important works during important periods of discovery.

In 1845, Sir Austen Henry Layard, a pioneering antiquarian in the study of ancient Assyria, started excavating a mound in Nimrud, Mesopotamia, eventually discovered the Palace of Ashurbanipal II, the early ninth century BC king responsible for the expansion of the Neo-Assyrian empire. At the same time, Rev. Austin Hazen Wright, class of 1830, who was serving as a medical missionary in Oroomiah, Persia, was asked by then College Librarian and Chemistry professor Oliver Hubbard to acquire some of the recently excavated murals for the College’s “young Museum.”

After a long and arduous journey through the desert, often on the backs of mules and camels, the murals finally made their way to the steamer Daniel Webster in Beirut and then on a train from Boston to New Hampshire, where they arrived on December 11, 1856. Dartmouth’s collection of murals, one of the world’s largest and earliest institutional collections of Assyrian murals, form an integral part of the collection of the Hood and offer one of the few opportunities for anyone to see a largely complete set, particularly after the 2016 ISIS destruction of whatever hadn’t been expatriated to museums internationally.

The next big bequest to the College’s collections came in 1912, courtesy of Emily Howe Hitchcock, the second wife of Hiram Hitchcock, an honorary member of the class of 1872. This formed part of a significant gift from Hitchcock, including the area occupied by the North Main Street entrance of Baker, all the way to the Connecticut River. Hiram and his first wife, Mary Maynard, were prolific collectors, procuring antiques from Ancient Egypt and Classical Greco–Roman Antiquity; their extensive collection of a few thousand artefacts added significantly to the study and development of collecting at the College.

In 1935, Nelson Rockefeller ’30’s mother, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, one of the founders of MOMA, donated to the College collection a selection of “more than 100 paintings, drawings, prints, and sculptures”; this constituted what Baas terms as “Dartmouth’s first important collection of modern art.”

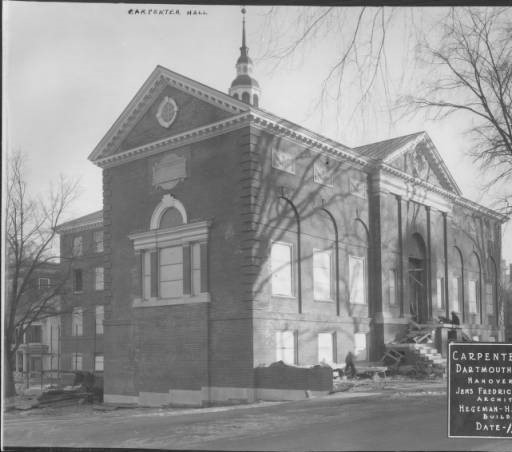

However, it was only under President Ernest Martins Hopkins, class of 1900, that Dartmouth’s collections were organized more systematically. The commissioning of the Baker Library and its subsidiary buildings, Carpenter and Sanborn, provided space for the collections to be organized. Carpenter Hall (completed in 1928–29), then solely the domain of the art history department, formed the axis mundi of the collections; the topmost floor featured galleries with large skylights and high ceilings to facilitate the exhibition and lighting of sculptures and paintings. Rare books were relegated to a specially constructed room at Baker. The architect of Carpenter Hall, Jens Frederick Larson, believed in a stringent but unique form of American neoclassicism that drew from Greco-Roman styles and orders of architecture, the forces of Georgian revivalism, and American history to create a building that reflected the noble simplicity and quiet grandeur that one would learn to expect from a college. The anthropology and natural science collections continued to be housed in Wilson Hall once the books were moved to Baker.

In 1974, due to an impending economic recession, the College divested itself of its natural history collections, keeping select artefacts only for study and usage. With the support of the College, the director of the College Museum, Dr. Robert Chaffee, took the collection across the river — and founded the Montshire Museum of Science. Despite the divestment, this was part of a period of disorganization. Baas, later the director of the Hood, writes that “the remaining operations of the College’s museum and galleries remained widely scattered. Five exhibition and three storage areas were in three separate buildings. And the museum offices and work space were divided.”

Fast forward to 1978, when Harvey P. Hood, class of 1918, a former trustee of the college, donated funds upon his death to house a larger, centralized focal point on campus where students, faculty, and community members could access the vast collections, which had swelled to 43,000 in number by then time the proposals were being considered for the Hood. The original plan in 1960 called for the Hopkins Centre to be the all-encompassing home of the arts — the old and the new alike — but budget cuts constrained the space available for the arts, which now manifest themselves as the Jaffee–Friede Gallery.

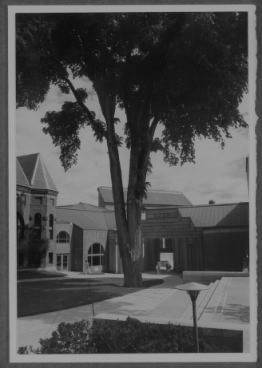

Under President David McLaughlin ’54, the architect Charles Moore was hired to squeeze the Hood in between the Neo-Romanesque Wilson Hall and the viciously modernist Hopkins Centre. Richard Teitz, the then director of what would become the Hood, heralded the new design as ushering in a new age for museum architecture and the conception of space. In a 1982 interview in the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine, Teitz claimed that Moore’s Hood building’s “most important component is its flexibility…As the collection grows and changes character, spaces and arrangements can be changed. We will not be locked in, as many museums are because they designed rooms around special collections.” Teitz lamented the costs associated with shifted the Sherman Art Library to Wilson Hall, next to the museum, begrudgingly accepting the $2.5 million simultaneous expansion of the Hop and Wilson Hall, adding facilities to reflect the growing nature of the College’s activities and the rise in enrollment.

The Hood was a turning point in the history of Dartmouth’s museum collections. In September 1985, the murals that Wright and Hubbard had so painstakingly bought to Dartmouth — as a certain Rev. Marsh, who had the misfortune of never attending the College on the Hill (he went to Williams), complained when the reliefs were being taken from Nimrud, “As Dartmouth had first choice, that college has a fine collection and little more than duplicates were left for us” — they were assembled painstakingly, once again, after a meticulous restoration at the Harvard University Art Museum, in the order that they were supposed to be placed in for the very first time after more than a century of disorganization.

The creation of the Hood as an entity also permitted the College to solicit donations to strengthen the weaker sections of the collection. Hilliard T. Goldfarb, the Curator for European Art before 1800, elaborated on the shortage of works from key periods in the history of art; in an article for the DAM in April 1986 Goldfarb complained that before the Hood’s creation, it “possessed no works representing the later Rococo and the advent of neoclassicism…[or] a single major Impressionist oil [painting].” Within a decade of its physical establishment, the Hood held pieces from significant artists, from the reputed and renowned Old Masters like Rembrandt to the so-called New Masters like supposed artist and well-known chronic abuser of paint and canvas Jackson Pollock. Roy Lichtenstein, known for his ability to photocopy comic books in an ungainly large format and sell it as art at the Leo Castelli Gallery, gifted Richard Serra’s alleged “minimalist masterpiece”, a variant of which collapsed upon an installer at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, killing the installer; the gift now lies in the walled-off courtyard behind the Warner Bentley bust.

One of the more controversial aspects of the Hood was not its collection and Jacquelyn Baas’ ‘anything can be art’ attitude, but Charles Moore’s edifice. Even today, it continues to be controversial. Roger Kimball, in the November 1985 issue of the New Criterion, calls Moore one of “the most prominent senior practitioners of that brand of self-consciously historicizing architecture that, for better or worse, we have come to call ‘postmodern’…[they] stand as admonitory reminders of the crisis in contemporary architecture.” The Hood was marked by retreat and escapism into the little space that it was constrained to; the history of art that it is the very temple of is pushed and shoved in between the theatricality of the Theatre department and the morose sobriety of the ex-library. The College, too, was responsible for the space that Moore was given to work with, but this ex post facto thought constrained the very ability of the Hood to become what it could have — a great College museum.

Tod Williams and Billie Tsien’s new building that builds upon Moore’s edifice, rectifying some mistakes and tearing down some of Moore’s signature flourishes. In an interview with The New York Times, Kevin Keim, the director of the Charles Moore Foundation, complained that “the entire conception of Moore’s building is being fundamentally wrecked…Charles Moore deserves better than this aggressive, ill-designed, shallowly considered project.” E.J. Johson, a professor of art history at Williams College, is quoted in the same NYT article as complaining that “it looks like they’ve dropped an enormous white cake on top of Moore’s building and just obliterated the whole thing.”

The newly renovated Hood Museum of Art opens January 26, 2019. It remains to be seen how the museum fares. Even though the new building doubles the space available to the Hood, it can only hold 1 percent of the permanent collection — the only question on our minds is, which 1 percent?

Be the first to comment on "The History of the Hood"