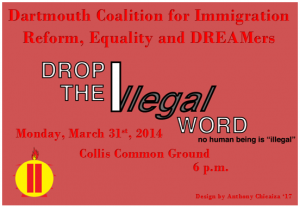

On April 2, 2013, the Associated Press dropped the usage of the phrase “illegal immigrant” from its stylebook, citing its unwillingness to continue its use of “illegal” to describe a person. The Los Angeles Times soon followed. Though ultimately unsuccessful, after the AP ‘s decision, protests were staged outside of The New York Times’ headquarters in an effort to push the paper in the same direction. A year later, the debate continues, as the students of the Freedom Budget, took up the issue with equal fervor. They asked the administration to “ban the use of ‘illegal aliens,’ ‘illegal immigrants,’ ‘[wetbacks],’, and any racially charged term on Dartmouth-sanctioned programming materials and locations. The library search catalog system shall use ‘undocumented’ instead of ‘illegal’ in reference to immigrants. [This must be] institutionalized in the Dartmouth handbook for students, faculty, and staff.” In support of this sentiment, fliers have recently been posted around campus demanding the administration censor these phrases.

Detractors claim the phrase’s flaw lies in its dehumanization of the immigrant. Its characterization of the average immigrant, who comes to the United States simply in search of a better life, as “illegal” incorrectly associates that decision with some sort of immorality. Yet not only are they wrong for coming here, the phrase posits, they’re wrong to stay. They’re labeled as “illegal,” —an “other” —liable to harm mainstream, moral American society. The alternative they provide, though, in “undocumented immigrant” is somewhat murky in terms of meaning. As The New York Times itself elaborated in its decision to keep its use of the term “illegal immigrant” (albeit while cautioning its journalists to use proper discretion to maintain appropriate usage of the phrase), ‘undocumented’ is the term preferred by many immigrants and their advocates, but it has a flavor of euphemism and should be approached with caution outside quotations.” After all, what exactly is an undocumented immigrant? It could be someone who entered the country without legal authorization, but it could just as easily be an immigrant undocumented due to administrative error.

Those who argue against the usage of the phrase “illegal immigrant” ignore the primary responsibility language has to accurate representation. Philosopher Josef Pieper, in his book Abuse of Language, Abuse of Power, points out, “First, words convey reality. We speak in order to name and identify something this is real, to identify it for someone.” Language is the only means we have to relate the world around us to one another. Its primary concern is truth. By entering the United States without proper processing, these immigrants actually did enter the United States illegally and, by extension, exist in the United States as illegal immigrants. In this sense, in focusing solely on connotation over denotation, the writers of the Freedom Budget miss the forest for the trees.

On the other hand, reframing issues by analyzing language has been a successful method of political advancement for minority groups in the US in the past, though. Most notably, the gay community successfully reappropriated the term “queer” from its prior derogatory use. Debates on language often serve as a proxy for debates on greater morality and social meaning, with implications that resonate past a simple collective adjustment in diction. In seeking to remove the stigma of illegality from these immigrants, however, they end up making the wrong statement altogether by endorsing conventional wisdom equating standing American law to morality and justice. We all know that there are plenty of instances where this simply is not the case, and in those instances, cogitative dissonance emerges when laws don’t line up with our intuitive senses of right and wrong. Anyone who has an opinion on abortion for example, whether it’s pro-life or pro- choice, is bound to have experienced this. Keeping this nuanced understanding, that the term “illegal” is a statement of fact in relation to our codified law instead of normative moral judgment, is crucial in maintaining the knowledge that our laws are can sometimes be problematic and when they are, that reform is necessary.

That being said, the term “illegal immigrant” actually fits better into our political lexicon’s language for reform. “The path to legal citizenship” touted by the Obama administration and their legislative counterpart simply has a clearer meaning than “the path to documentation,” especially since, at the end of the day, the problem isn’t documentation. We know who these people are: they are overwhelmingly economically motivated by the promise of improved income and livelihood for self, family, and friends and by the promise of safer streets and stable government. They are stifled by legal immigration routes that are so backlogged that many are assigned decades-long waits before they can even enter the United States. In many cases, they pay taxes in their paychecks, work below the federally mandated minimum wages, and in turn support the same government that stoops to populist demagoguery and demonization in border states and even on the national scale.

At the very least, though, there’s value to be had in avoiding banning all of these words in any capacity. For every bigot we silence from using these terms, especially the terms “wetback” and “illegal alien,” discourse will concurrently suffer. These terms have become, for better or worse, a part of our history. The term “wetback” was originally used for Mexican-Americans who waded, or swam across the Rio Grande into the United States. In the 50s, newspapers used the term frequently, especially to describe the case of 1954’s “Operation Wetback,” a deportation drive that is now remembered mostly for racial profiling and breaking up families. Once “wetback” was recognized as offensive, “illegal alien” entered our vocabulary, often with an equal tone of derision.

This was not the last failing of American public empathy to occur. There will likely be more in the future. Preserving these events in our minds, as well as our ability to talk about them, makes us more prepared to deal with our challenges, and failures, in the future.

Be the first to comment on "The “I” Word At Dartmouth"