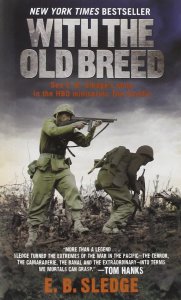

While the Second World War has been written about as extensively as any armed conflict in human history, far more of the available literature is devoted to histories of famous campaigns, battles, generals and political leaders than to the enlisted “common man’s” experience during the war. While a number of enlisted men’s memoirs do exist, With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa, by Eugene B. Sledge, is widely considered to be the best. In the book, Sledge covers his service with the United States Marine Corps from his enlistment in December of 1942 through two major island campaigns, and ends with the Japanese surrender in August of 1945. The most compelling strengths of With the Old Breed are the quality of Sledge’s observation and his written “voice”, which allow him to capture the experiences of enlisted infantrymen, warfare’s lowest common denominator, and relate them in such a way that readers can almost imagine the frustration, boredom, elation, terror, and brutality that characterized his combat experiences. First published in 1981, Sledge’s writing has enjoyed a popular resurgence in recent years after featuring prominently in the highly acclaimed HBO miniseries The Pacific.

With the Old Breed begins with a brief description of Sledge’s decision to enlist in the Marine Corps from his home in Mobile, Alabama, in December 1942. He relates that he initially planned to complete the V-12 college training program, which would have given him a commission as an officer upon graduating from Georgia Tech. However, he and many of his fellow students feared that the war would end before their graduation occurred, so they chose to deliberately flunk out of their academic program and were immediately reassigned to boot camp as enlisted men. Boot camp meant a trip by rail from Atlanta to San Diego, followed by eight weeks of rigorous introductory training at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot there.

Upon graduation from boot camp in December 1943, Sledge was assigned to the infantry and spent several more weeks near San Diego in infantry training. It was at this point that he volunteered to serve as a member of a 60mm mortar squad (a mortar is a small, man-portable piece of artillery that fires shells at an extremely high angle so that they plunge down on enemy positions or troops from above). After completing infantry training, Sledge finally deployed to the Pacific theatre in late February 1944. Throughout this description of the training process, Sledge does an able job of highlighting the anxiety, pride, and occasional moments of humor he and his fellow recruits encountered. The most interesting part of this segment was his awareness and observation of the confident, somewhat distant personality exhibited by the combat veterans he encountered in San Diego. This theme of a dichotomy between the outlook of raw recruits and veteran marines continues throughout the remainder of With the Old Breed, with Sledge himself making the transition from the former to the latter during the Battle of Peleliu.

The first six months of Sledge’s deployment to the Pacific theater were free of any combat experience whatsoever. His first stop was the major American staging base at Noumea, New Caledonia, where he spent two months conducting further training with a replacement battalion before finally being assigned as a replacement to the combat unit with which he would serve for the remainder of the war: K Company, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division (The 1st Marine Division is known colloquially as “the old breed” due to its long combat history, hence Sledge’s choice of title for his memoir). Joining his new unit required another ocean voyage from Noumea to the small island of Pavuvu, on which the 1st Division was recovering and reequipping after the Cape Gloucester campaign of earlier that year.

Sledge did not encounter the Japanese on Pavuvu, but he uses his description of his time on the island to illustrate that an infantryman’s life can be hell even without the horrors of combat. Whereas Noumea had been a large, well-supplied base, Pavuvu was an improvised staging area and left much to be desired in terms of living accommodations. Among the hardships Sledge describes were muddy roads and living areas, weevil-infested rations, a constant stench of rotting coconuts from the copious groves surrounding the camps, and a large population of land crabs which continuously invaded tents, beds, and boots. After enduring Pavuvu for most of the summer, in late August Sledge and the rest of the 1st Marine Division boarded landing ships and sailed west for what would be his first combat experience: the Battle of Peleliu.

Of the numerous island-hopping battles fought in the Pacific theater by the Marine Corps during WWII, Peleliu has not been remembered nearly as well as other engagements like Guadalcanal, Tarawa, or Iwo Jima. Sledge notes this fact for readers and thus prefaces his experiences during the campaign with a brief strategic overview of the command perspective behind the invasion. Essentially, Peleliu was viewed as a useful island airfield to be captured in preparation for the upcoming Philippines invasion, with U.S. commanders estimating that the island could be taken within three or four days when in fact it took over a month of brutal close-quarters fighting to dislodge and destroy the 10,000 Japanese defenders (whether taking Peleliu was truly necessary is a subject of controversy to this day). Sledge chronicles his thoughts and emotions from the night before and morning of the invasion in excruciating detail, and while the combat to come was unlike anything most readers will have experienced, his description of mounting anxiety is eminently relatable (though admittedly on a lesser scale) for anyone who has felt stress over an exam, job interview, audition, tryout, or other major event.

After this buildup, Sledge then takes readers through his combat experiences on Peleliu, including storming the beach as part of the second landing wave and conducting an assault across the open ground of the airfield the next day under intense Japanese artillery fire. He described this latter experience as “terror compounded beyond belief” and as his worst memory of combat from the entire war. According to Sledge, surviving the airfield assault was the moment at which his perception of himself changed from untested recruit to veteran. After establishing positions on the southern area of the island and taking the airfield, the remainder of the Peleliu campaign consisted of evicting the main force of Japanese defenders, who were heavily entrenched in a rocky mountainous area on the northern and western portions of the island that became known as “Bloody Nose Ridge”.

The Marines made excruciatingly slow progress during this phase and suffered extremely high casualties, as the Japanese took advantage of the natural defensive features in the steep, rocky terrain and had to be burned or blasted out of every single position. Sledge and the rest of the 5th Marines saw their fair share of this action, during which a Japanese sniper killed his company commander, Captain Andrew Haldane. In addition to the violence of combat, the hellish situation was compounded for the Marines by chronic shortages of drinking water, an inability to bury corpses or latrines due to the hard coral ground, and temperatures that frequently reached 115 degrees Fahrenheit or more, which kept the men exhausted, produced a horrific stench from the unburied dead, and attracted enormous numbers of huge flies.

Even when his unit was not on the frontlines of the fighting on Bloody Nose Ridge, Sledge relates that the threat of attack was still constant, as the Japanese would send small one or two man infiltration teams behind American lines at night to attack sleeping Marines with bayonets and grenades, leading to confusing and terrifying encounters in the dark. In addition to the sheer brutality of combat, Sledge uses the Battle of Peleliu to illustrate another major theme of the book: the dehumanizing psychological effects of combat. Specifically, he offers an incredibly perceptive commentary on the extreme racism and xenophobia that allowed Marines and Japanese soldiers alike to commit atrocities unlike anything seen in most other theaters of the war (in which the opposing combatants were often from more similar racial and ethnic backgrounds).

Sledge’s account of his second major campaign, the Battle of Okinawa, bears many similarities to Peleliu. While the overall strategic picture was quite different, as the war in the Pacific was nearly over and Okinawa represented the final island stepping stone before an invasion of the Japanese mainland, Sledge’s experience as an infantryman was fairly similar, with close quarters combat required to dislodge the Japanese from entrenched positions. The climate on Okinawa was different from Peleliu but equally miserable, with constant rain and the resultant choking mud replacing the oppressive heat. Sledge remained on Okinawa after fighting had largely ceased and was there when the Japanese surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, at which point his narrative ends.

With the Old Breed is one of the best WWII memoirs out there. While there are better books for understanding the broader strategic perspective of the Pacific War (Gordon W. Prange’s Eagle Against the Sun is a great place to start), Eugene Sledge’s writing does an unparalleled job of allowing readers with no military background to comprehend the full human experience of infantry combat in two of the most brutal engagements in modern military history. With the Old Breed is the perfect pick for anyone with an interest in the Pacific War, WWII infantry combat, or stories of survival in the face of unimaginable hardship.

Be the first to comment on "The Old Breed in a New Century"