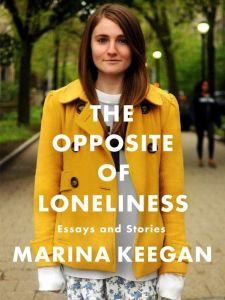

The cover of The Opposite of Loneliness shows a young woman standing on the sidewalk, tightly framed against a blurred-out background, from mid-thigh to the top of her head. She has long brown hair that hangs down against a mustard-yellow pea coat with large black buttons, below which a white skirt with a blue floral pattern peeks out a few inches. Her arms are straight by her sides and the sleeves of her sweater extend over her hand in way that is endearingly childish. Her expression is understated and yet extremely engaging as she stares straight ahead into you with a mouth that is not smiling but appears to be in the process of beginning to do so. It looks like she is thinking about something other than being photographed. This girl is Marina Keegan. She is dead.

The Opposite of Loneliness is a collection of some of the more exemplary stories and essays Keegan wrote from her high school days up through her time at Yale, from which she graduated magna cum laude in 2012, set to begin a job at The New Yorker. She was killed in an automotive accident five days after graduating when her boyfriend fell asleep at the wheel.

One could call her death a tragedy but that would involve a misuse of the term, which refers to a literary genre in which some awful mistake leads to an individual’s downfall. If anyone’s the tragic figure here, it is her boyfriend, except that he was immediately forgiven by Keegan’s parents and thus freed of a life destroyed by guilt. Keegan’s death is a whole other kind of thing that haunts the book in a way that resists description and is not present when reading any other book by any other author, even if he or she happens to be dead, too.

The essays and the stories range in quality, length and topic. She writes about the ethics of saving beached whales, about the life of a pest exterminator, and a lot about the romantic and sexual lives of young college students: boyfriends, girlfriends, drugs, parties, a lot of crying. She writes candidly but not coldly about her experience living with Celiac’s. Probably her best essay, in my personal estimation, titled ‘Even Artichokes Have Doubts’ concerns corporate recruiting. As a Dartmouth senior currently hunting out something to do next year, it seems, hundreds of my peers have already secured lucrative positions in finance and consulting—professions I hadn’t even heard of before I came here.

Unlike many of my peers who are uninterested in or incapable of succeeding in finance and consulting, I don’t voice a lot of vociferous opposition to the funnel so many of my peers sink into after having matriculated with dreams of doing art or teaching. This is because I try to maintain level of reasonable empathy: I want to have a comfortable life too, and people come from all sorts of different backgrounds that make them accustomed to different levels of privilege. Foremost, I know how the petri dish of campus culture makes it exceedingly difficult to stand out without feeling left out, and how the prospect of departing from a highly-structured environment into the open arena of the Real World is frightening to a young person. I feel like it’s problematic that such a large portion of America’s brightest youth go in one directions; but I know I’d be doing it too if I could do math or had any connections at all.

This is what I like about Keegan’s piece. It isn’t just a vicious polemic against the greed and complicit evildoing of her classmates. In fact, it’s not that at all. Keegan genuinely and empathetically explores the emotions and plans of her peers at all levels. She, too, is concerned about the trend, but she is trying not to be ignorant. Her writing manages to tastefully blend hard and soft research with narrative and analysis, something that’s hard to do and takes a great deal of thoughtfulness. The consequence is that it feels authoritative without feeling authoritarian, sympathetic without being condescending, and smart without being smartass-y.

The other thing about this piece, as well as many of her other essays and stories, is that it’s so immediately concerned with the future—not in the sense of “What’s the future going to be like? Will there be flying cars? Lightsabers? Will Google buy out the U.S. Government?” but in the sense of a personal future, a heightened conscious that certain young people feel when they realized that they’ve been allotted only a certain portion of time and they’ve got to do something with it that’s worthwhile. The tragic (truly tragic) irony here is that, despite Keegan’s romantic decision to shirk the path most travelled and pursue the career of a writer, her portion of time was far less than what she’d anticipated.

This is the unintended dimension that enriches all of her writing, including when she contemplates how she will eat differently when she’s pregnant (which she never will be), what will be on her gravestone (which was inscribed far sooner than she could have known), or what it means to have ‘forever’ in a romantic relationship. Somehow this makes everything much more vivid. If Keegan were still alive and I were reading about her college senior aspirations, it would be less compelling because I would always wonder whether they’d been mutated or abandoned. But in The Opposite of Loneliness I find a picture of a young woman’s personal future that will be preserved forever.

“The Opposite of Loneliness”, the essay after which the book is titled, is, incidentally, probably the best example of this kind of sentiment and at the same time probably the worst essay in the book. Keegan asks why there isn’t a word for the opposite of loneliness, even though this is a secret feeling we all strive after. I don’t think this is anything profound; I think most people don’t need to be told that they don’t want to be alone and that relationships create meaning and that ‘togetherness’ is probably a decent term for whatever she says the opposite of loneliness amounts to.

But regardless, the point is that Keegan’s voice is one that, while admirably not pretending to be wise beyond her years, is still wise in orientation. He stories strive at meaning and profundity (she seems to like the word ‘profundity’ too), asking lots of big questions and are to be left unanswered until they are graced with experience and maturity, or perhaps never.

The foreword, written by Anne Fadiman, recounts how an undergraduate Keegan reacted to the pronouncement that in this day and age, it’s impossible to become a writer. Instead of feeling discouraged, she felt all the more determined to make it, constantly writing and perfecting. And she was poised to have some success, writing award-winning plays, working for Harold Bloom, and interning at The Paris Review. The fact that she was killed, naturally, also killed this dream.

Or did it? Ostensibly the point of the publishing this anthology was to say “Never fear, Marina, you will become a posthumously famous writer.” When I first began to read her book, however, I had some dark concerns: This book has sold very well and become very popular since the prospect of reifying a young girl’s lifelong wish despite the hazards of morality is very attractive. Many people, quite understandably, feel sorry for her, or just feel objectively bad about all the lost talent. But, if the reason people are reading her book is because they feel sorry or guilty somehow, doesn’t that undermine Keegan’s authentic dream to be admired for her writing, not for her biography?

The concern evaporated by the time I began reading her fiction (I read the non-fiction first, even though it is second in sequences within the actual book). Her stories, while mostly plot-less, were unbelievably organic. They seemed to be milked straight out of her real life, or at least some imagined life or lives that could not be distinguished from what you’d encounter on the street or in the classroom. Some of the stories seemed more like embellished diary entries because they were so personal. Let alone that, thematically, there was a good deal of probably accidental correspondence with her “real” life: for example, the very first story is about a college girl whose boyfriend dies and the ensuing emotional complication. Similarly, Keegan repeats names, like Sam and Kyle. It’s impossible to not notice the repetition, and it reminds one of the creative unity that endures between apparently unrelated stories: they have the same author, they were created by the same person.

All this makes Keegan feel comfortably present with the reader as he or she is reading in a way that, in my experience, only occurs with certain authors: Plath, Seneca, D. F. Wallace, and Waugh. By contrast, when I read Dostoevsky, I don’t feel his presence. I feel like he is either dead and a million miles and years away in a Russia on another Earth, or he doesn’t exist at all. But I feel like I am seated beside Plath when I read her journals; she becomes truly undead to me and I almost feel like we’re friends, bizarrely.

This supernatural effect, whereby the distinctions among author, authorial persona, character, and book are erased, constitute in my estimation the hallmark of a really gifted writer. Holding the book in my hands, especially staring at the cover, I feel like I’m holding something so personal it’s actually a kind of person. So, ultimately, it’s not to Keegan’s discredit that people initially only read her book because they are trying to do something for a dead girl with a sad story. If you read the whole thing, you come away with the feeling of having made a genuine kind of connection with someone in just the way she wanted you to: by reading her writing. That is the best thing that can happen between a reader and an author and it defies time and space. It achieves, in a funny kind of way, one form of the opposite of loneliness.

Please share the name of the author of this review

I would like to contact them if possible