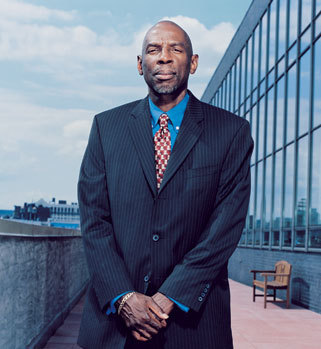

The Superman of the South Bronx, Mr. Geoffrey CanadaIn one small chapter of the interminable quest to reform education, the HOP last night put on another showing of Davis Guggenheim’s documentary Waiting for “Superman,” having previously shown the film last January. Since I’m currently in Istanbul (more on that another day!), I naturally could not attend, but I did attend the January showing. The film was intended to precede a visit to campus by Harlem Children’s Zone founder Geoffrey Canada, a major figure in the film, but blizzards forced the postponement of his visit until this term. Presumably, the second showing of the film was to remind everybody that education was not magically fixed in the last three months.

The Superman of the South Bronx, Mr. Geoffrey CanadaIn one small chapter of the interminable quest to reform education, the HOP last night put on another showing of Davis Guggenheim’s documentary Waiting for “Superman,” having previously shown the film last January. Since I’m currently in Istanbul (more on that another day!), I naturally could not attend, but I did attend the January showing. The film was intended to precede a visit to campus by Harlem Children’s Zone founder Geoffrey Canada, a major figure in the film, but blizzards forced the postponement of his visit until this term. Presumably, the second showing of the film was to remind everybody that education was not magically fixed in the last three months.

Thankfully, “Superman” wastes no time in answering its most burning question: Why on Earth was it titled Waiting for “Superman”? At the very beginning, Geoffrey Canada speaks of how he grew up in the slums of the South Bronx and was always waiting for Superman to arrive and save the day. When told by his mother that Superman is not real, Canada was crushed, because from his viewpoint nobody but Superman could solve the Bronx’s monumental problems. To his credit, Canada eventually took it upon himself to play the role of Superman, becoming first a teacher and later the president of the Harlem Children’s Zone, an innovative educational nonprofit which is a major focus of the film.

With the force of a biology textbook to the head, “Superman” lays out in almost humiliating fashion how America’s schools have fallen into ruin. It is a welcome jolt, since the sorts of people who watch documentaries (or attend Ivy League schools) come disproportionately from private academies or the posh public schools of high-end suburbs, and they could be forgiven for failing to notice the catastrophe around them.

As the film demonstrates, America’s education crisis is not equally spread among schools but is instead centered on particular districts and schools that serve as “dropout factories” where less than half of all students graduate high school. Be it at the level of elementary, middle, or high school, at some point students in bad districts suffer through a point where their education is completely derailed.

So if the problem is so obvious and exists all across the country, what is holding up reform? The film points several fingers. One culprit is the sheer complexity of the educational system, or as the film calls it, “the Blob.” America has over 14,000 school districts, and in addition to local school boards there are state boards of education, as well as the federal Department of Education in D.C. Every one of these entities produces its own rules and regulations, creating the ideal environment for bureaucracy to run rampant while accountability is left by the wayside.

More distressing, though, is the role played by teachers’ unions. Much of the film’s middle portion details in grueling fashion just how badly teacher unionization has damaged American schooling. Rather ironically, the reason this is so is because teachers’ unions more than any other group block the development of a world-class teaching corps.

As is made clear by the film, good teachers are essential to successful schooling. A top-of-the-line teacher is able to cover not only a year’s planned curriculum, but 50% more as well. In contrast, a poor teacher will typically cover only 50% of the curriculum. This shortfall is difficult to make up, and is nearly impossible to overcome if students have to endure consecutive years of poor teaching. Therefore, successfully educating America’s children requires that bad teachers be aggressively identified and eliminated.

Unfortunately, this is not happening, and it is almost entirely on the heads of teachers’ unions. While even good teachers support their unions and likely have only the best intentions, the simple truth is that as things currently stand unions are the Cerberus blocking off the gates of reform. Although the film never quite mentions it, the underlying cause of this is a mindset which treats teachers as entitled to their jobs. Instead of being recognized as individuals entrusted with building America’s future who must be ruthlessly tossed out if not up to the task, teachers enjoy absolutely unrivaled job security.

As most people know, the key element of this job security is tenure. Originally established to protect professors and teachers from meddling by politicians or monetary donors, tenure is now absurdly given to teachers even at the elementary level after just a few years of service. Once tenure is granted, firing a teacher becomes immensely difficult. In one damning statistic, the film notes that while more than 1 in a 100 lawyers or doctors eventually lose their professional certifications, only 1 in 2500 teachers suffer the same fate. Another factor impeding teacher turnover is a deliberately gnarled bureaucracy. In one district, 23 steps over the course of an entire year must be completed before a teacher can be fired, and if certain deadlines are not rigidly met the entire process must start over.

Thanks to the twin hammers of tenure and bureaucracy, school districts are forced to take ridiculous measures to offset the effects of bad teachers. In New York, hundreds of teachers charged with various violations are taken out of the classroom and placed in so-called “rubber rooms,” where they wait for weeks, months, or even years while drawing full pay and benefits waiting for their cases to be heard (thankfully, this practice is now being eliminated). In Milwaukee, the so-called “dance of the lemons” occurs, where bad teachers are passed along from school to school in the hopes of minimizing their damage.

Although a few hope spots are included, the general tone of “Superman” is one of all-pervading gloom. A major narrative focus of the film is on a handful of children whose families have entered them in charter school lotteries to try to save them from bad schools. Sadly, it’s hardly a spoiler to say that most do not get in, and the viewer is left to wonder whether these children will fall into the same educational maw that has already consumed so many millions.

Unfortunately, in a fate it shares with so many other worthy advocacies, “Superman” falls short when it comes to driving the angry but aimless masses towards genuine action that will create change. The film’s creators would have done well to read and learn from the recent book Switch by Chip and Dan Heath, which offers sage advice on how to generate change where change seems so difficult. While the film excellently presents the problem and showcases efforts to fix it, it botches the job of explaining how viewers can help fix America’s schools. The ending is a rather bland sequence of text that looks like the beginning of the credits; in fact, at the HOP showing the lights went up and people began to file out, an event which probably occurred at other showings as well.

That said, those who walked out without reading did not miss much. The ending merely restates the severity of the crisis and then declares that the viewer must become an agent for change. The viewer needs to “get involved” and demand it, in fact. This generic call to action has a host of problems. The film itself is full of despair; it pulls no punches in showing both the depth of American educational failings and the huge difficulty involved in solving the problem. While this makes the problem plain as day, it also instills a great degree of helplessness in the face of an overwhelming foe. To motivate the viewer to do something rather than merely wait for Superman to fix the problem, the film needed to present a clear path forward. Instead of urging people with boring text to “get involved,” the film could have told them to vote for school board members and state representatives who will advance policies such as ending tenure, expanding school choice via vouchers or charter schools, and curbing the influence of teachers’ unions. The more specific the plan, the easier it would be for people to act on it. Ultimately, raising awareness won’t bring about change; only action can do that.

–Blake Neff

Be the first to comment on "The Superman Cometh"