When I first pulled my advanced reader copy of Sarah McCraw Crow’s most recent (and, as I would come to learn, first) novel from the tattered cardboard bin in the corner of the musty breakroom of the building in which I am currently employed, I admit, I did not expect much from the work.

It seems inappropriate, at first glance, to enter into what is sure to be a somewhat lengthy digression into my discovery of the book, although I argue that the circumstances in which this noel found its way into my hand are uncannily similar to my experience of the story itself and therefore unquestionably relevant to my review of its contents. Furthermore, though it certainly lends no credence to my justification, my fellow editors at the Review will be quick to tell you that, when writing, I am not one to shy away from diatribes, nor will I hesitate to grandstand. Some call it fluff; I call it an unhealthy obsession with Donna Tartt.

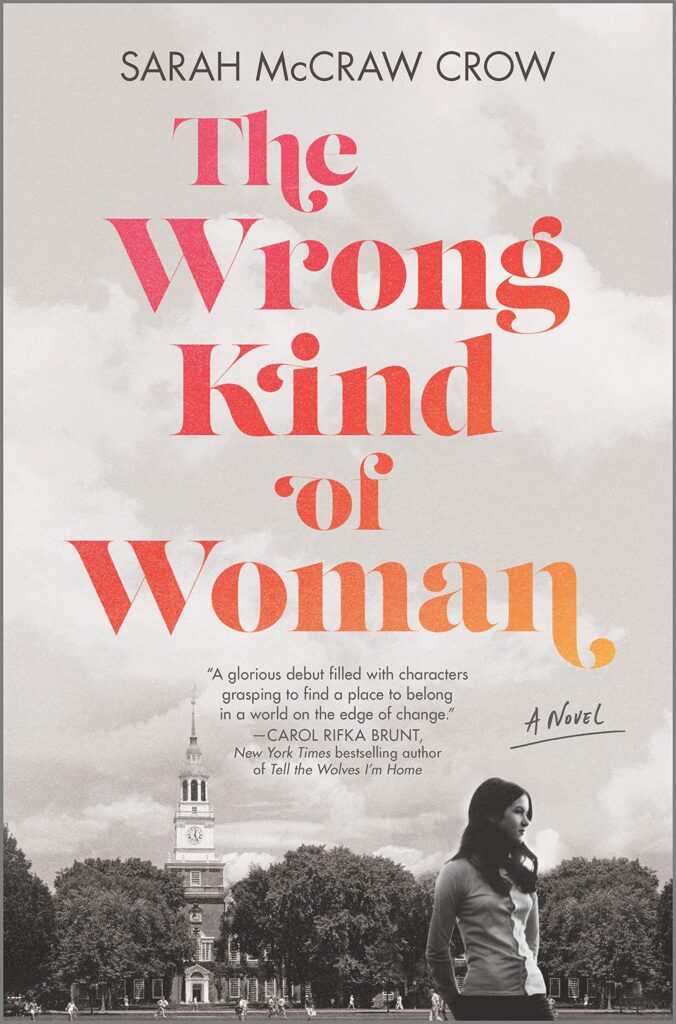

This winter, stranded as I am in my home city of Knoxville, unwilling to submit myself to the panopticon that is Dartmouth Administration, I found myself somewhat suddenly in the employment of a certain corporate bookseller that will remain unnamed (though, if you live in the States, feel free to guess, I can nearly guarantee you’re spot-on). The job itself is exactly what you expect, though perhaps even more mundane, however it does come with perks any perpetually bored English major such as myself would appreciate, including unfettered access to a box of ARCs that fills itself at the whim of a publicist and empties itself into the hands of college students such as myself who are far too busy working for just-above-minimum-wage to take the time and effort to promote the books, which is presumably the box’s intended purpose. I was hired relatively late in the holiday season, so my first few weeks of work saw the box left only with the absolute dregs of new releases, the undesired airport fiction titles the other employees had neglected to take even for free. After a bit of time, I noticed the box was once again full, and I decided to spend one of my valuable 15-minute breaks perusing what it had to offer. I saw a book with Baker’s iconic clock tower (weathervane still standing) on the cover, and, filled with nostalgia for a campus on which, after a year and a half of being enrolled as a student, I have spent two terms, took it home with me.

Later that evening I was surprised to see the book was not featured on the Review’s list of titles to be, well, reviewed for the upcoming issue, a shock you can only truly appreciate once you understand the extent to which one of our editors scoured the farthest reaches of the Internet to find any recent title even tangentially related to the College. To give you an idea, one of the many titles not included in this issue is a poetry collection written entirely in Russian, which we neglected to read for the simple fact that none of us (to my knowledge) read Russian. Why did you even include that, Parker? What could you possibly hope to gain?

After justifying my existence and place on the masthead to the organization by finding a book that had somehow slipped through the cracks, confirming that not only is Crow’s novel about Dartmouth, but she herself is an undergraduate alumna, I sat down to read.

I was, initially, disappointed. Crow’s The Wrong Kind of Woman has chosen an excellent setting for itself. The bulk of the plot revolves around the campus of “Clarendon” College in the early 70s, a place already ripe with potential conflict due to its position as both a cultural hub of rural New England, a slow and sleepy place even by my Southern standards, and as an institution catering to the front lines of the New Left, radical students and thinkers who have, by the opening of the novel, already once stormed the president’s office in the past few years. Layer this with Clarendon’s specific conflict of the decision as to whether or not include women amongst their future undergraduates, and introduce characters themselves replete with inner contradictions, and you have a story with the potential to unravel in Faulknerian proportions. Crow’s opening chapters left me fearful that she would neglect to take advantage of the setting practically sizzling with potential. I admit, my expectations for her objectives for the novel were determined in large part by the cover design (which, aphorisms be damned, is a central aspect of the form of the book and should never be overlooked), one that reeked of pandering to centrist Liberals and performative feminism, an enormous mistake on the part of the marketing team. Of course, Crow’s earliest passages do nothing to ameliorate this misstep, as the exposition seemed not the least unique to New England and the mentions of political struggle were inserted forcefully and uncomfortably, making the protagonists seem, frankly, quite stupid.

This began to change towards the end of the first fifth of the book, when Virginia, one of our few central protagonists through which we experience Crow’s evolving world, sees a book in a store downtown, and considers buying it for her husband, Oliver. The sentence is so benign, so forgettable, until, a moment later, Virginia catches her breath sharply and begins to pace in circles around the bookshelves in a vain attempt to tamp down her mounting anxiety. You see, Oliver died in the opening scene of the novel, a fact that Virginia, in her initial stages of grief, often forgets; in fact, the reader, when absorbed in the quotidian activities of Virginia’s life, often forgets alongside her. This is not a fault in Crow’s writing, or a failure on her part to capture the gravity of the death of Olier; on the contrary, it is her masterstroke. Crow has the impressive ability to capture human grief in an inexplicably human way: tied imperceptibly and unavoidably to our chores and routines, our limits of activity and habit, the blank spots in our memory and our subconscious refusal to confront pain. It was at this point that I recognized in full Crow’s capabilities as a writer and communicator of emotion; it is also the point at which the book began to hit its stride.

From then, it is impossible to ignore the degree to which each of the characters is plagued by faults, and not romantic mortal flaws that spell doom for the classic heroes (tired tropes at this point, wouldn’t you agree?), but faults that are integrated fundamentally into our bones and neurons, faults that manifest in the characters just as they might in the crust of the earth: miniscule and invisible until the ground is falling away from under us. Crow forces the reader to reconcile with these faults, urging us to beware, for they are the true root of pain and conflict, the defining feature of the human position in the world, the devil in the detail.

The plot itself sees its fair share of dramatic and violent political and social turmoil. There are protests on campus, threats to economic security, acts of terror, even, to put it intentionally plebian, explosions. One could quite effortlessly take the plot of Crow’s work and fashion it into a political thriller if they wished. Yet Crow, thank God, refuses; instead, she uses the backdrop of strife to highlight the fissures underlying the characters’ psyches. The grief that follows the untimely death of Oliver is only the first of such examples, and though it seems the least consequential from the perspective of national and international political struggle, Crow’s focus on grief and phenomena reveal the existential equality of all such events in the lives of the characters.

This is not to downplay the political work done in her novel. Crow’s depiction of conflict between liminal characters who stand in for subalternated classes performs the labor of art, it illuminates the points of tension and seeks reform and resolution at these points. If anything, The Wrong Kind of Woman is not existentially apolitical but existentially super-political; the struggles Crow paints are fundamentally human struggles and are thus grounded in actual phenomenon, not the theoretical abstract. When read well, Crow’s novel serves as a story of feminism as a human conflict, not a story of feminism told from the mouths of mere advocates.

This is not to say I had not complaints with Crow’s work. As I mentioned earlier, the opening of the novel is quite bland. Further, while there are several instances of shining prose that compel my breath to catch in my throat and my heart to race, there are other moments when the prose seems simply unpolished and unprofessional, a fault that cannot be excused by Crow’s status in the world of novel composition as a beginner, as she has previously published several articles and short stories, and consequently should be well-disciplined in the gritty craft of writing. Additionally, some of the arcs of the characters, particularly that of Elodie, the young radical who comes from a background of wealth and finds herself caught up in the exhilaration of political action, feels unfinished and unsatisfactorily unexplored. Perhaps the worst fault is found in the story of Sam, an undergraduate from New York, whom Crow alluded to having been either sexually or at least romantically involved with Oliver, his professor, at some point in the near past. This leaves Sam feeling conflicted about his sexuality; I expected this conflict and the unresolved tension with the late Oliver to comprise the bulk of his development, yet the entirety of his plotline revolves around his sexual fascination with Elodie, and his queerness as a point of exploration for the novel is dropped entirely.

These faults do not, however, pose an overwhelming threat to the quality of Crow’s work as a whole. By the end of the novel I found it to be not only a memorable but important piece of contemporary literary fiction, not to mention its obvious interest to those with even a passing interest in College history.

Be the first to comment on "The Wrong Kind of Woman: A Review"