Reading these concerns, one might be forgiven for thinking that President Hanlon recently announced a seven-day academic week or the demolition of student health services rather than some earlier class slots and limits on grade inflation.

Late last month, The Dartmouth Review published an issue that examined the state of education at the College. In it, we were rather critical of the Hanlon administration for its failure to make the curriculum an obvious priority during its landmark Moving Dartmouth Forward campaign. At the time, we wrote that the classroom had been “glaringly absent” from recent conversations about campus life and concluded that “the administration seemed to have neglected its age-old focus on the academic aspects of student development” in its zeal to remake Dartmouth socially.

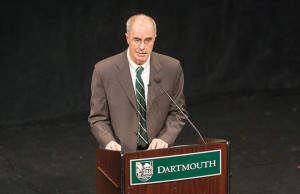

Needless to say, we were rather chagrinned when two days after we distributed that issue to campus, President Hanlon revealed the specifics of his Moving Dartmouth Forward proposal. In his January 29th address, the campaign’s main themes of sexual assault, high-risk drinking, and social exclusivity took somewhat of a backseat to scholastic rigor and the promise of the College’s academic character. In fact, between his introduction and closing remarks, President Hanlon spent over a third of his speech addressing Dartmouth’s commitment to the liberal arts and the importance of intellectual engagement within campus life. Such a focus was as commendable as it was unexpected, especially given the nine months of hyperventilating about the College’s social system that preceded it.

Judging by the reactions of some students, however, others on campus didn’t find this surprise nearly as pleasant as we did. In the days since the announcement, many around the Green have been heard criticizing the substance of Hanlon’s academic initiatives. One student in particular took to social media to lament the College’s decision to “make Dartmouth, home of too much stress and inadequate mental health services, MORE academically rigorous… .” It got over ninety likes. Another noted that “the [Presidential] Steering Committee failed to realize that Dartmouth is already academically demanding” and advanced proposals that didn’t support a healthy “balance” in student life. Others still complained that “[the proposed changes] will not stop kids from going out” and will instead “punish the rest of the hardworking student body,” which is “stressed and sleep-deprived enough as it is.”

Reading these concerns, one might be forgiven for thinking that President Hanlon recently announced a seven-day academic week or the demolition of student health services rather than some earlier class slots and limits on grade inflation. In reality, the substance of the proposals does not merit the current state of alarm. Provisions like mandatory classes on the Friday before big weekends and the creation of the occasional 8A are hardly going to mean the end of fun and balance on Dartmouth’s campus; instead, they will make but minor changes to the classroom experience that most students already know and love. More than one faculty member has even characterized the reforms as “completely innocuous” and “largely platitudinous.” The student reaction, by comparison, is comically disproportionate and only lends credibility to the idea that Dartmouth undergraduates are so under-stimulated that the mere suggestion of an 8 AM class is enough to send them running for their pitchforks.

To be clear, this is not to dismiss some of the aforementioned concerns out of hand. Dartmouth as it stands is hardly akin to a four-year vacation in the wilderness: its ten-week quarters and existing academic expectations are more than enough to tax even the most brilliant among us. Few would contend that simply piling on some vaguely “rigorous” measures is going to have a positive effect on campus life. But to insist that earlier classes, fewer A-median courses, and a greater emphasis on experiential learning (whatever that means) are going to send the student body hurtling past its breaking point on a Dick’s House gurney ignores the specifics of what has been proposed and borders on the realm of the ludicrous.

A far more valid criticism, however, might be found in the administration’s emphasis on “rigor” as its new academic buzzword. Reading through the substance of Hanlon’s January 29 address, one cannot help but wonder if he has selected the wrong word to describe the right goal for his forthcoming reforms. In the introduction of his speech, Hanlon noted that the College should aspire to a campus “that is even more intellectually energized, a site of significant academic entrepreneurship and innovation, a place of big ideas, bold efforts, and path-breaking scholarship.” The list of suggestions that followed, though, has little promise for making those ambitions a reality: are we really to believe that a partnership with the Aspen Institute, calls for lower medians, and more class hours will restore the College to some erstwhile era of scholarly excellence? Like President Obama’s supposed “redline” in Syria, these ideas appear to be more the product of short-term expedience rather than a recipe for long-term success.

What the administration should be emphasizing — and what it sounds like Hanlon’s address was trying to convey — is a desire for a greater intellectualism in campus life. A student’s experience in the classroom should not be divorced from the ways in which he elects to spend his free time outside of the library. Instead, the two realms ought to be mutually reinforcing. As the student body vice president, Frank Cunningham, asks in his interview with The Dartmouth Review, “why not create a culture in which you can ask your professor to go out to PINE tonight and talk about the lecture over dinner?” His point is well taken. What student life needs now more than ever is a greater integration of the academic with the colloquial. And the key this marriage will be the presence of the faculty outside of the classroom.

For all of its flaws, Hanlon’s Moving Dartmouth Forward plan seems to understand that professors need to take on a greater role in student life. That’s why it’s taking a page out of Yale’s playbook and is including faculty in its forthcoming residential college model. But if this drive toward a greater intellectualism is to succeed, more than just live-in advisors and intra-dorm programming is needed. Instead, Dartmouth’s scholars must commit to a larger role as undergraduate mentors and students need to make seeking them out a priority. Only then will the high rhetoric of “academic rigor” translate into the type of educational experience that the campus wants to see.

Be the first to comment on "Toward a Greater Intellectualism"