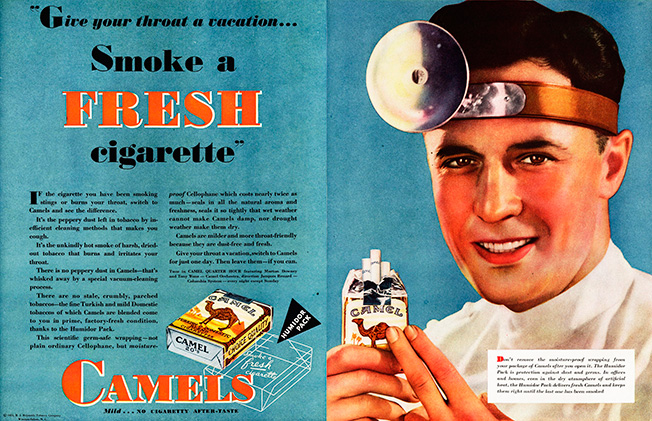

The Dartmouth Man has long been expected to be a master of fire. In the brutally cold New Hampshire winters, the sliver of hope and comfort is the heat a fire brings. Students were once expected to chop or collect their own wood in order to heat up their living or outdoor spaces. Despite this no longer being a necessity, the annual Homecoming Bonfire honors the spirit, where students gather around and rejoice at the beauty of warmth and vitality. Fire is thus an integral part of the Dartmouth experience. This tradition persists further in the act of smoking. The cigarette symbolizes man’s control over fire: in the face of a vast winter landscape, he lights his cigarette and warms his lungs, embracing the cold, for he can endure it—even if only for a moment.

Furthermore, fire encourages community. For thousands of years, humans have gathered and bonded around crackling fires. Smoking extends this practice as great conversations and experiences can be born of going through a pack of Camels with friends or colleagues. The sharing of a cigarette or a tobacco pipe is itself a beautiful sight, and even more so with strangers, which requires an unreciprocated act of generosity. One shares his fire with another for the sake of camaraderie and community. There is nothing more fitting to describe the role of cigarettes than Boyle’s confession in Rand’s Atlas Shrugged:

I like cigarettes, Miss Taggart. I like to think of fire held in a man’s hand. Fire, a dangerous force, tamed at his fingertips. I often wonder about the hours when a man sits alone, watching the smoke of a cigarette, thinking. I wonder what great things have come from such hours. When a man thinks, there is a spot of fire alive in his mind—and it is proper that he should have the burning point of a cigarette as his one expression.

Over two years ago this week, President Hanlon announced the College’s “Tobacco-Free Policy.” The policy prohibits smoking and the use of tobacco products within all facilities, grounds, vehicles, or other areas owned, operated, or occupied by Dartmouth. including all outdoor spaces, as well as public streets and sidewalks within twenty feet of the entrance to a Dartmouth building. It applies to anyone stepping foot on (or near) Dartmouth’s campus and grounds, including students, faculty, staff, administrators, contractors, and visitors. If one visits the College, he or she will soon realize the hollowness of Hanlon’s declaration and the reality on campus. Those who want to smoke will smoke. The College’s solution to smoking, the “Quit Kits,” are free prepackaged goodie bags filled with everything a smoker might need to get started on the road to abstinence, “such as fidgets, sugar-free gum,” and generic-brand nicorette. Oftentimes, these kits can be found in fraternity basements, pillaged for the intensely concentrated nicotine chewing gum, with the gadgets and candies that accompanied them stuffed in some forgotten container, like Woody and Buzz.

This vision of a tobacco-free campus—or more appropriately, a nicotine-free campus, as the ban implements measures that target more than tobacco smoking—has failed. And it is tainted not only by the College’s lack of concern for the voices of its students, faculty, and staff but also by its ignorance of both the individual and communal experiences that define the College and its history. The solution to mitigating “a variety of life-threatening diseases, including COVID-19” as Hanlon noted is not to ban tobacco as a whole. As responsible, college-educated students, those who do not want to risk second-hand exposure can simply remove themselves when those around them are smoking or using tobacco. However, the College has decided that, instead of allowing students to be accountable decision makers, the solution is to medicate those who will not or cannot conform. Touting the “cessation resources” available, the College offers another form of drug to restrict students from consuming a drug that they voluntarily choose to use.

Long gone are the days of In loco parentis, under which colleges would assume parental responsibility over their students. Since the 1960s, this power has deteriorated due to the courts having recognized further constitutional rights for students, thereby restricting universities’ ability to regulate student life. Nevertheless, the College, especially with policies like the tobacco ban, are expanding their control over students, transforming them into wards of the institution. The College should not be accountable for the consenting, personal decisions of adults, and its institutional power and influence should not change that fact. If decisions like these continue to be made based on shielding students from the potential dangers of life choices, we lose a valuable phase of maturing and developing into Dartmouth men and women prepared for reality.

Moreover, the way in which the College applies the ban—to spaces not just owned and operated but also “occupied” by Dartmouth—is unsettling. Not even the public roads, sidewalks, or the Green are safe from the ban, which highlights the reach of the policy. Without approval from the Town of Hanover, a tobacco-free campus that includes property and spaces not owned by the College is an excessive overextension of power. While the College emphasizes that “state law allows Dartmouth to establish rules regarding tobacco use on its property,” does the College have the authority to control open-air spaces if college facilities merely “occupy” adjacent areas? This ambiguity sows distrust regarding the College’s rules, and it infringes upon the beauty of being a student in New Hampshire, where we can supposedly embrace nature without the gazing eyes of Big Brother. The College even demands that students share responsibility for “enforcing the policy.” Enlisting students to carry out disciplinary policies deepens the current divisions that began with the College encouraging students to report their fellow friends and acquaintances for minor COVID-19 infractions. It is as if the Red Guards of the Cultural Revolution were not a powerful enough lesson against incentivizing those within a society to turn against each other. Or, possibly, the deterioration of student unity works in the best interest of the Administration.

We, the authors, wish to clarify that we are not opposed in principle to the limitation of personal freedom in order to promote public welfare. However, any instance which sees a substantial decrease in personal freedom and only a marginal increase in public welfare is utterly unjustifiable. The College’s tobacco ban represents such an instance. As a result of the tobacco embargo, well-being on campus can only be promoted in three ways: aesthetically improving the campus, decreasing harm to the non-smoking population, and decreasing harm to the smoking population.

In the case of the aesthetic improvement of campus, there is, we suppose, an argument to be made. However, it is doubtless one with which we would vehemently disagree. Some find the sight (or smell, though this is easily enough avoided) of a smoker repulsive and would prefer the act to be relegated to unseen spaces. Yet the logic of purging smokers from campus due to aesthetic repulsion is abhorrent. This is a patently ridiculous reason for banning all tobacco-based products—if you are repulsed by the sight of a smoker, then D.A.R.E. may have done a better job than we gave it credit for.

Smoking also causes very minimal harm to the non-smoking population on campus. We do not deny the malignant effects of exposure to second-hand smoke, which have not only been researched and rehashed ad nauseum, but have afflicted one of this article’s authors personally in his youth, as he has moderately severe asthma and an aunt who at one time smoked frequently. This author wants to stress, however, the complete nonissue that is exposure to second-hand smoke in uncrowded outdoor areas. It is absurd to suggest that banning the use of tobacco products (not only combustables, but chew, pouches, and any other nicotine-based substance) across the entirety of spaces even tangentially related to the College would improve the well-being of pedestrians due to reduced exposure to second-hand smoke. It is simply far too easy to avoid smokers in a public setting as is, and many are happy to accommodate the flow of foot traffic by smoking far from populated areas in the first place.

The only instance in which we may see an increase in well-being, depending on one’s definition of the term, is in the population of smokers or users of nicotine who quit because of the College’s policy. However, many affected by this ban—despite the announcement’s graphic and egotistically paternalistic depiction of smokers—are not addicts. Rather, they might enjoy sharing a cigarette with friends on the weekend, or Juul occasionally to curb a jolt of anxiety, or act as mere hobbyists who smoke a pipe or cigar irregularly. The long-term health of individuals such as these will not be substantially improved by the College’s injunction. Rather, they will merely have fewer means of expressing themselves, exploring their individuality, and unwinding from the stresses of undergraduate study by enjoying a hobby.

Furthermore, it is questionable whether the ban will truly benefit those who are legitimately addicted to cigarettes or nicotine (most of whom, anecdotally, seem to be working-class college employees and contractors). Sure, they may now have a decreased risk of developing cancer or other complications in the future, something of which they were already aware. But that would be if, and only if, they do in fact quit smoking, rather than trek out of their way to smoke off college property or risk disciplinary action by sneaking a cigarette. Yet the College’s treatment of this population, much smaller than the entirety of individuals affected by the ban, seems morally untenable and not at all worth the benefits. The policy will encourage further ostracization of smokers and increase the taboo of nicotine consumption, something socially harmful not only to groups we have already discussed but also to those for whom tobacco use factors into religious ritual. But the College’s plan for countering the fall-out of their ban—articulated formally online as “Faculty and staff can access a variety of tobacco-cessation resources, including medications…”—seems to be to simply drug the poor bastards, a Huxleyan turn barely masked. And thus the tobacco ban is philosophically insupportable: it crosses the threshold into action that promotes the public good at a much greater expense to individuality and personal freedom.

Smoking, and the consumption of tobacco or nicotine-based products in general, has developed into quite the taboo within contemporary American culture. What was once a generally accepted practice among all, from the poorest of farm-hands to the wealthiest of aristocrats, has now been relegated to the status of an unseeable and revolting practice of the “lower classes,” thanks to a campaign that the United States federal government has waged at full force. Good has undoubtedly come from the American elite’s newfound hatred of smoking (an icon of Yuppie culture), in the form of a dramatic reduction in health complications as a result of smoking. Nevertheless, it seems we are nearing the peak of potential good, if we have not already surpassed it. We are now entering the realm of pure limitation of individual freedom, done for the sake of homogeneity and the promotion of the scientistic sterility that undergirds neoliberalism.

From a portable alternative to the comparatively laborious process of smoking from a pipe, the cigarette has become an emblem of the anachronism of the working class, the stubborn refusal to “believe in science” and follow the professional managerial class into the present. It mirrors the elitist perception of the rural poor as stupid, outdated, smelly, and without place in contemporary discourse. Chewing tobacco has followed the same path, coming to represent the stereotype of the racist hick who dips seemingly in sheer defiance to the Enlightened Liberal. The College’s formal policy, though clearly sanitized for an acceptable and inoffensive presentation to its intended audience, reeks of the aesthetic revulsion that defines the relationship between nicotine and the elite. This is seen most clearly in the policy’s sheer refusal to acknowledge the existence of those who smoke occasionally, not out of habit but out of genuine and benign pleasure. Indeed, it addresses only what it considers to be the poor unfortunates who have yet to be purified by the wonders of scientism, who are too stupid or too hopelessly addicted to help themselves, and who must be rescued (read: be medicated) via the benevolence of the College.We like smoking. We particularly enjoy the social aspect, the flavor of a well-blended and thoroughly spiced Virginia, the focus it lends us, the consistency of its ability to take the edge off a particularly violent panic attack. However, even if we had never smoked in our lives, even if we personally found the experience disgusting, we would be just as opposed to the cultural objectification and infantilization of adults who consensually partake of tobacco. No being with agency should be subjected to such subtly toxic subversion by a wealthy, homogenous elite. No culture should have to forsake itself at the behest of a more powerful Capitalist Scientist. Here, in this article, we have enumerated and elaborated on our grievances with the College’s nicotine ban, which is celebrating its two-year anniversary. We at TheReview believe in the freedom of students, faculty, staff, visitors, and all who step foot on campus to not sacrifice their individuality for the sake of sterilization. We at TheReview support the democratization of College decision-making and oppose recent efforts by the Administration to ignore the desires and concerns of the Dartmouth Community. We at The Review oppose wholeheartedly the College’s nicotine ban. Vox Clamantis in Deserto.

Be the first to comment on "Untenable, Unjustifiable, Un-Dartmouth: The Two-Year Anniversary of College’s Tobacco Ban"