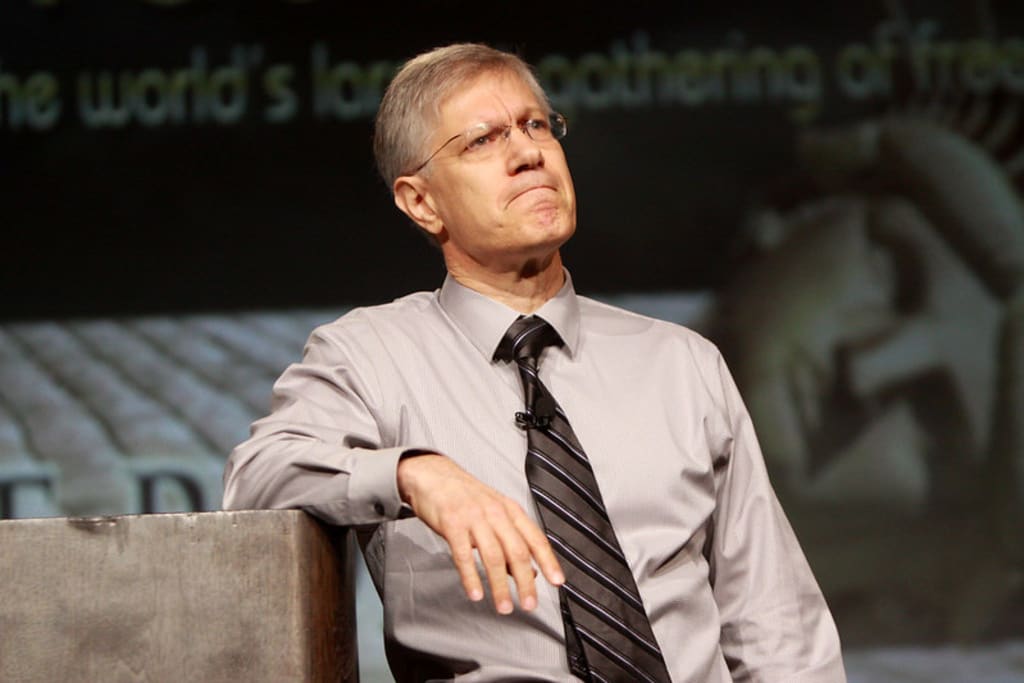

If there is one thing that was important about the Dr. Yaron Brook speaker event titled “The Moral Case for Capitalism” that we, the Dartmouth Libertarians, hosted at the end of last term, it was that the event served as an introduction to the possibility that there is a whole set of moral theory that defends capitalism that many real people have adopted. I hoped that the event—as such an introduction—could encourage people to evaluate the premises of the defense of capitalism and try to understand the motivations behind the argument in a fair light.

As a student of philosophy, I am always cautious not to reject a conclusion in and of itself, independent of the premises and reasoning that lead to the conclusion. The conclusions of some arguments may seem intuitively wrong. But the next move should not be to dismiss the arguments as a whole but to evaluate the premises behind those conclusions and understand where they differ from your premises and where they went wrong. To reflect on premises is important to anyone who wishes to arrive at better arguments. More importantly, to reject someone’s conclusions without understanding their premises, to me, is an act of disrespect. The political culture today endorses this kind of disrespect, and both the Right and the Left are guilty of it.

The night before Yaron’s event, I decided to table in Novack—the student cafeteria in the main library—with other members of Dartmouth Libertarians. We asked students to write down arguments in favor of and against capitalism on a poster divided into two columns. It was meant to get the conversation going and our peers curious about what arguments can actually be made, and we were motivated partially because many of our posters for Yaron’s event had been taken down around campus. That night in Novack, many students, to our surprise, argued in favor of capitalism, and many more were genuinely interested in having a real conversation and learning more on the topic.

Hours in, two girls stopped at our table. One of them saw that there were many responses under the “For” column arguing in favor of capitalism, and asked us, “who wrote these?” We said, “people who walked by.” She asked again, “Are you sure you didn’t?” Granted, she could have been genuinely astonished by a) the notion that Dartmouth students would actually write down arguments in support of capitalism, or b) the notion that there are actually so many points that can be made in support of capitalism. However, there were many alternative ways to communicate that surprise, and many of them would not have implied that we were lying.

Immediately, there was tension in the air. I remember feeling distrust directed toward me, and the judgement. I was scared that she would not understand me, and I was eager to clarify. The conversation ended with her talking about how she had to move to this country because the U.S. ruined her country’s economy and her friend saying, “read some critical race theory, love.” Soon a male student who was also present asked us “do you realize that in being a libertarian you are actually endorsing the U.S. empire?” After I tried to explain that we advocate for individual liberty and peace and absolutely not aggression, he wrote down “fuck y’all.” We were all shaken up. All I could think to say was “well, that’s not a very friendly thing to say,” which only led to a verbal reiteration of “fuck you” and a storm-out. I shouted at his back: “but you didn’t make an argument!”

I should make it clear that this encounter does not represent the overall campus reception of us in the slightest, but it was still a highly educational experience. It is one thing to watch videos like this on YouTube, and another to experience it myself. The male student looked at me with an expression that I can only describe as hatred. A couple of days later, when I retrieved that memory, I felt offended, not because of what they said, but because they thought it was okay to disrespect me—to say “fuck you” without knowing who I am and to assume that I was lying. I believe that the idea that it is okay to disrespect a complete stranger like that is a product of the premise that those who disagree with communism or socialism are not only wrong but also immoral.

I take great issue with this kind of premise not only because it discourages real conversations, but because it deteriorates the very interpersonal fabrics of an inclusive—yes, inclusive—community. Ultimate inclusivity is not about having a more diverse makeup for the sake of it, but to overcome the active rejection of diversity and embrace what we all share deep down. A truly inclusive community allows us to look past how we differ in terms of objective features such as gender, sexuality, or race, and recognize people in their most authentic forms, which include their thoughts—i.e., an interplay of values, premises, and conclusions—as well as the willingness to discover yet another person by understanding theirs.

To disagree is one thing, but to disrespect is another. If that’s true, then what I want to ask is this: What justifies the disrespect one has for her intellectual or ideological opponent? A value I hold dear is to always try to see the world through the other’s first-personal perspective, which is the next step after having recognized someone in their most authentic form. I am actually very tempted to call this “love.” If thoughts are indeed part of one’s authentic form, then their philosophical premises are part of what you would genuinely evaluate if you recognized their humanity. I believe this is a deeply egalitarian principle that we should endorse here at Dartmouth. To observe the world as it discloses itself to someone else from their perspective is to act on a sort of “loving attention” that Iris Murdoch, a moral philosopher, argues for. This deeper reason for freedom of speech and expression and intellectual discourse, then, is not something that one can easily reject without running into some sort of a contradiction: a rejection of freedom of speech is often done in the name of love and inclusivity, but it itself actually constitutes a rejection of both.

Many people regard those who defend capitalism as immoral people who deserve disrespect, and that is a problem that transcends politics. It is not about what we argue or who is correct but about how we perceive one another, especially those with whom we disagree the most. I invited Dr. Brook over to mediate that preconceived notion and show my friends here that there are people who have written and talked about the moral argument for capitalism extensively for many years. To be clear, that does not mean that their arguments are right. It simply means that there are real people who have thought about this deeply, and the arguments they make are worth listening to for that reason. Today, it is the moral case for capitalism that challenges the kind of disrespect that we hold against our political foe collectively and automatically. Tomorrow, it may be “the moral case for coercion,” or “the economic case for socialism,” and I can only ask that those arguments be incorporated into the broader discussion as well, especially if the people who are making these arguments are dismissed and deemed “immoral.”

Lastly, my colleague at The Review made an important point at the end of his report on the event published in the last issue of Winter Term 2020. He mentioned that to help others seems to contradict rational self-interest, and that presents a problem with Dr. Brook’s claim that people would donate to charity if they acted out of self-interest. Dr. Brook may argue that it is, in fact, very much in one’s own interest to help another; one may want to see less suffering in the world, one may want to donate to medical research because she wants to protect herself from developing certain conditions, etc.

But let us also consider the alternative to acting out of one’s self-interest. To me, (imposed) altruism presents a big contradiction: if everyone is supposed to sacrifice herself for someone else, then no one is valuable—i.e., no one is worth sacrificing for. Second, I think it ultimately comes down to two options: I help others either because I feel ashamed if I don’t, or because I want to. Our culture has a disdain for the “I-want-to.” However, if I don’t help others because I want to, then I am doing it out of fear of my own inadequacy, which can hardly constitute a truly moral act. In that sense, a lack of coercion and force in a society is necessary for the individual moral architecture to arise. One must choose to do good herself, and to truly choose to do something herself is to act in one’s self-interest. This is how individualism—as a prerequisite for goodness—underlies the moral case for capitalism.

From an existentialist’s point of view, I believe that to recognize the freedoms of others, help others realize their own freedoms, and leave them to live the lives that they choose themselves to the extent that they do the same for others, is the ultimate moral act. What I take to be Ayn Rand’s most important message is this: there needs to be both an “I” and a “you” for there to be an “I love you.” To recognize a “you” is to immerse myself in your worldview and genuinely evaluate your premises and conclusions. My colleague at The Review expressed a dismissive attitude toward Dr. Brook because of some on-the-spot and casual comments he made. It is really easy to highlight one or two things that someone says as evidence that their entire broader argument is of no value. It is much harder to listen and to understand—really understand—what they are saying on a deeper level, and I think the attempt to listen and understand constitutes an act that is far more moral than to scoff at someone who is trying to make an argument. I have much personal affection for my colleague, and I could only hope that he—or anyone else—would call me out if I make the mistake that I know for a fact I have made many times before. And to the three students in Novack that night: I could only hope that we can give each other a fair hearing one day, not for the sake of an ideological or even philosophical win, but for a communal one.

Isn’t the United States’ economic imperialism a decent moral case against capitalism?

I’m not surprised if a lot of people defended it. There are obviously lots of pros, lots of cons, no one will deny that. However it’s not just an idealogical debate for a lot of people. And I think saying that people’s “authentic” selves are different from their race, gender, class, or any other “objective” feature isn’t a great take and definitely minimizes their very real impact on people’s history and experience. I like philosophy too, but I don’t think you can separate out “morals” to be considered in a vacuum when the topic has so much tangible historical weight and evidence.