Courtesy of the San Francisco International Film Festival

Editor’s note: On Wednesday, October 4, Editor-in-Chief Matthew O. Skrod (TDR) interviewed the acclaimed film critic and historian David Thomson (DT) about his career and his time at Dartmouth, as a professor and latterly Director of Film Studies, between 1977 and 1981. Mr. Thomson is widely regarded as the world’s greatest living writer on film.

TDR: Thank you, Mr. Thomson, for taking the time to talk with The Review. Would you be able to situate your time at Dartmouth in the context of your early career? And what brought you to Dartmouth in the first place?

DT: I began teaching in 1971 in England, when a small liberal arts college in New Hampshire, New England College, established an English campus. I taught there part time, and in 1975 they asked me to go to their American campus and teach there, which I did. While in New Hampshire, I visited Hanover and saw Dartmouth, and I was impressed with it. Then I had various family upsets, including the death of my mother, and I had to go back to England. But I was told by a friend that there was a job opportunity at Dartmouth, and I applied for it.

Maury Rapf, who was in charge of film studies at Dartmouth at that time, contacted me and asked, “Is there a chance you’re going to be out here? We’d love to interview you, and we regard you as a serious candidate.” As I recall, it was in the spring of ’77 that I was at Dartmouth and went for an interview. It was a day-long interview, where I taught a class; it went pretty well, and the College offered me the job. All of a sudden, I found myself a full-time teacher of film at an Ivy League school. I needed the job, a place, and I had no idea how exciting and eventful it was going to turn out to be.

I owe my presence there really to Maury Rapf’s instinct and spirit of adventure. He was a very important figure in my life. When I taught the sample class there, a lot of students came to it, I remember, and they were the best students I’d ever seen. I realized this could be an interesting and exciting venture.

Maury had something that only came from having been born into the industry and grown up in it. And he was a very smart, educated man—a Dartmouth man, himself, of course. He had a strong sense of the realities of the film industry. I’ve always held and still hold the view that, while there are obviously geniuses and charlatans in the industry, it is at its heart a business, and it’s very difficult to get far in it without understanding it’s a business and paying some respect to that. That came from Maury, and he reinforced it. We had lots of conversations just about his past life, and I liked him a lot. Maury was also very good at getting Dartmouth alumni, film-related people from the past to come visit campus—people like the screenwriter Walter Bernstein and others.

In my experience, there were also people in the language departments who had quite a big influence on what was going on in film. When I first came to the College, Neil Oxenhandler was a professor at Dartmouth. He was an authority on Jean Cocteau, among other great French filmmakers. There were people in the German Department also who had very good knowledge of German films.

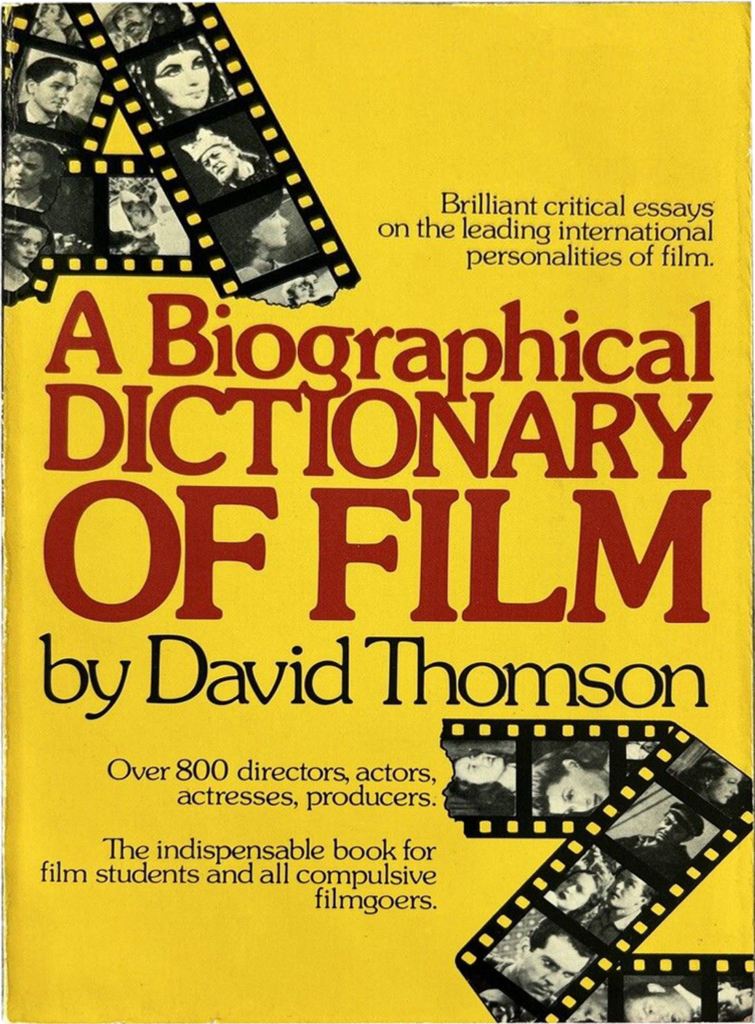

TDR: I have before me a first US edition of your epochal Biographical Dictionary of Film, published in 1976, one year after the first UK edition came out. So, you wrote this book, and it was twice published, before you even came to Dartmouth.

Throughout your career, you have written—if I may say so—with exceptional authority on the history of film as a whole when discussing individual people or films. I see that trend as early as this first edition of the Biographical Dictionary. How did that come about? Were you a prodigious viewer of films growing up?

DT: I started going to the movies at the age of four, and it became a sort of family tradition with my parents, my aunt, and grandparents that if they had me on their hands for a day or a weekend, they would take me to the movies, where I would be content.

I have always loved the medium in an absolutely uncritical, unconsidered way. I just love being in the dark, looking at the big screen and the light. I loved books, I loved reading, I loved history, those things. But it was only when I was involved in what was a fairly serious education in England that I realized film was the dominant imaginative force in my life.

I still went to the movies as a teenager some three or four times a week, which meant going out to the theater. We didn’t have a TV set until I was about 17, and I just absorbed everything. I didn’t mind what I went to see. I would sometimes go to a movie theater just to be there, unaware of what the film was. Gradually, through the 1950s, I started paying attention to the credits and learned that there were certain people—like Nicholas Ray, Anthony Mann, Vincente Minnelli—that were pretty reliable names. I found that I would often especially enjoy films which had those names attached to them. That was the beginning, I suppose, of a certain kind of critical orthodoxy.

Anyway, to cut a long story short, I was aimed at going to Oxford. I actually secured a place at Oxford. But when the time came, which would have been about 1959, I really couldn’t face staying in academe longer. I had noticed, in Sight and Sound, advertisements for the London School of Film Technique, which was the only place in England where film was being taught at all. And I decided I would go there instead of Oxford. This was a major decision—all my teachers told me it was an absurd, catastrophic decision, the biggest mistake I would ever make in my life. But I still went, and the school was indeed terrible at that time. It has since turned into something much better as the London Film School, but at the time it was a very bad school, very unorganized.

But I met a group of other students, and we had a ball. We made films; we shot pieces of films. I had never attempted filmmaking before that, but I loved it, and I found that it was deepening my sense of how films worked. I started going to the school in 1960, and by then, I was probably seeing at least one film every day. Sometimes more.

The school’s own screenings were not that good. London in those days still had a lot of repertory theaters that would screen old films, and by then I had become a member of the National Film Theatre, the theater of the British Film Institute. That, really, became my university. I never went to any proper university. I went to the NFT, the National Film Theatre, with several friends day after day. That’s where I had seasons on the history of French film, that kind of thing. It was a crucial developmental stage. I just tried to see everything I could. Compared with people of my age, by the time I was, say, 25, I had seen a hell of a lot of films.

My mother had earlier given me some great wisdom. Even when I was a teenager, she was alarmed that I was going to see so many films. She thought it was not really what I should be doing. And she said, “Well, if you want to go see these films, I’m going to ask you to write something about them.” So, every time I went to see a film, I had to write a sort of review. These reviews weren’t long—200, 300 words. But they represented the first time I had tried writing about film. And I put myself through the discipline of asking myself what was happening on the screen? What was it doing? What was it doing to me? Why did I like some films more than others? That kind of thing. It was the beginning of a kind of critical education, which I still have. I don’t see as many films as I used to see, although, these days, because of the explosion of media, it is actually easier to see lots of films.

When I was a kid, you couldn’t see many films. I didn’t see Citizen Kane for about four years because it was unavailable. Nowhere was it being screened. Then it suddenly came out again. Anyway, that’s a nutshell version of what happened to me and is still happening to me.

TDR: I imagine you were going to see both films on first release and retrospectives? So, you would have seen the theatrical release of, say, Vertigo, in 1958?

DT: I would attend screenings of both current and old films. And yes, I saw Vertigo. I was one of the few people in ’58 who thought Vertigo was a good film. Of course, when Vertigo opened, it was a flop—it was badly reviewed generally. I thought it was staggering in its atmosphere. It seemed to me a major film. I wouldn’t have ever ranked it as the best film ever made, but it was and is a major film.

TDR: It was also one of the five films that Hitchcock withdrew from circulation in the 1960s, and which weren’t screened again until after his death. Was it interesting teaching about Hitchcock in that interregnum?

DT: It was. I remember at Dartmouth, in the late ’70s, students would come to me and say, “You saw Vertigo, didn’t you? Tell us about it.” And I would. I would recount the film in plot terms. It was an amazing thing, and obviously it was a tribute to Hitchcock’s genius as a showman. By withdrawing the film, he increased interest in it enormously.

TDR: When you arrived at Dartmouth, the first British and American editions of the Biographical Dictionary had already been published. What was the genesis of that book? What motivated you to compose so vast and authoritative a compendium?

DT: I worked for a Penguin Books for a time, and I knew a guy in publishing in London. He said to me one day, “You seem to know more about film than anyone I know.” It was an age, in the early seventies, when there was a huge interest in world cinema. All the New Waves had broken on the shore, and this changed everything. People who had grown up thinking that you went to the pictures or the movies once a week suddenly realized that there was a vast climate of films, often made by young people and more cheaply than in the past, that were as lively and compelling as the best books, the best music, or the best paintings.

This guy proposed, “Why don’t you write a book that describes the whole picture?” It was intended at first to be an encyclopedia, but as it developed, it became a biographical dictionary. I showed it to him as a work in progress, and he said, “No, that’s good. Keep it up. Keep going.” He said at the time, I remember, “What I like about it is that there’s a passion or opinionated feeling to it. Don’t lose that. Don’t make it a calm, objective, academic book. Make it a passionate, personal book. Make it a book that angers people sometimes. Go for what you really feel.” That’s just what I did, and initially that upset some people.

The book did not get reviewed very much at first, but by the time I came to Dartmouth, it had been reviewed quite widely and generally favorably. It had upset some people, but the book was a very important calling card in my getting the job at Dartmouth.

TDR: And it attracted the interest of a US publisher as well. I haven’t read the first UK edition, but I imagine it was the same text as what appeared in the first US edition?

DT: Indeed it did. And as I recall the text was exactly the same.

TDR: It’s very interesting to flip through the six different editions of the book, if I may say so, and see the revisions that you’ve made over time.

DT: By the third edition, the book had moved in America from William Morrow to Alfred Knopf, and this was in the glory days of Knopf. Bob Gottlieb became editor on the book by the fourth edition, and Bob was falling in love with the movies himself. He and I had a wonderful, long-term relationship coast to coast. We would argue, and he would propose people who should be in the book, and that kind of thing. It was probably the most creative writer-editor relationship in which I’ve ever been involved. In that process, the book grew much larger. By now, it’s about twice the length of the original edition. It features many more people—still not nearly enough, of course. Also by the time of the fourth edition, the book was really taking off and selling very well, which did my career a lot of good.

TDR: The Third Man seems to have gone up in your estimation through the various editions of the book. Your view of its director, Carol Reed, also seems to have gone up, if rather less substantially. What you have to say about Welles, rather than Reed, being in some sense the author of The Third Man struck me as very interesting in the context of the 1970s, shortly after Pauline Kael’s infamous reconsideration of Welles. Your opinion strikes me as something that Bogdanovich would have seen in the same way.

DT: Oh, I should think so. It’s interesting that you mention Bogdanovich. He was one of my first American friendships. Around the time I came to America, I remember writing to him, suggesting a movie.

And he responded, “Oh, it’s a great idea, and I’ve just made it.” It was the idea, he thought, for Nickelodeon, which I don’t think was a very good film. But still, what I suggested was a story about the very early days of filmmaking, and he and I became quite good friends. You know, his career went up and then sharply down. We were friends until the end, and I actually did an interview with him within months of his death.

He was a wonderful storyteller and a wonderful impersonator of a lot of the people he was writing about. He did a very good Hitchcock, for instance.

TDR: Could you discuss your involvement with the broader topography of film at Dartmouth and what courses you were teaching?

DT: One of my job requirements was to be the faculty advisor to the Dartmouth Film Society. When I arrived, I formed a warm friendship with the student leadership at the Society, so I had a lot to do with the programming it put on. The Film Society was a major part of Dartmouth life then. Week after week, we would show a film and get something like a thousand people seeing it. There wasn’t as much alternative viewing then as there is today. Film Society events were very, very big, and that was a part of what I did.

As far as what I taught, there was a big introductory class that I co-taught with Arthur Mayer in his last year at Dartmouth. Mayer was a wonderful old man, by the time I knew him, who had been raised in the business. There was, again, that sense of someone being rooted in the film business, because he’d been an exhibitor of films. I managed the course and ran group discussion sections. There was also a two-part history course that I took over. I would teach parts one and two in back-to-back terms. I also taught seminars. I did seminars on Renoir and Welles, which I remember very well. Probably the liveliest course that I taught was an introduction to filmmaking, in which students would make super 8mm films. We’d send the film away to a laboratory in Boston, and it would come back the next day. It was very exciting, and what made that course work, I believe, was that the students who had done the history and criticism courses were also doing filmmaking.

Many of them discovered a wonderful interplay. Things they’d seen in, say, a Renoir film were happening in the little films that they were trying to make. It was a very good group of students in those days. There were several people who went on to careers in film of some kind. They were great classes to teach. I was far from an expert in filmmaking, of course, and eventually we hired a filmmaker, David Parry. But the idea that film appreciation and filmmaking were locked together has always been a big part of my approach to teaching film.

At the time, film was very much part of the Drama Department. In those days the Department would put on a summer repertory program in theater. But in the summer of ’81 we actually shot a movie instead, called Interstate. The film grew out of some plays I had directed, and it involved a group of student actors: Justin Monjo, Heather McCartney, Carmine Iannaccone, Julia Mueller, and Jim McNeil.

Here’s a very interesting story, about one of the things I did at Dartmouth that probably had lasting effects: Near the end of my time there, I proposed a new course, an introduction to television, which had never been taught. I remember going before the curriculum committee and pitching this new course. The chair of the committee was Leonard Rieser, the provost of the College, a man who had been involved in the Manhattan Project. He asked me, in a friendly way, “David, why do you think television should be taught?” And I said, “I can think of a couple of reasons. One of them is that Dartmouth produced Pat Weaver and Grant Tinker, two absolutely major figures in the history of TV. The other reason is that many students at Dartmouth have certainly spent more time watching television than reading books.” He asked me, “Can that really be so?” I said, “Well, you talk to them, and you’ll find out that it is so.” Happily, we got the course through.

Now, of course, Dartmouth has a Film and Media Studies Department, and obviously everyone understands that the two are married. It’s terribly important that they are studied together, and television has probably changed the world at least as much as film has.

That was a daring, novel idea for people like Leonard Rieser, who was a very smart man. I don’t mean to say that we had a conflict over it, but he asked at one point, “What do you think is the most important thing in the lives of our students?” And I replied, “Well, they obviously have a huge range of interests, some of which I don’t even know about, but I think responding to TV is a very big one.” He said, “But surely it’s living under the shadow of nuclear weapons?” And I said, “That’s a big thing, obviously, but that’s been the same every day of their lives. But every day, TV has something different to show, and many of them are so absorbed in it that they can quote whole passages from silly TV shows.” Looking back on it, it’s amazing that that should have been the case: that media had not yet really moved into the center of intellectual consideration. That course was a beginning.

Courtesy of Dartmouth Archives

TDR: We’ve discussed in brief the critical reaction to your Biographical Dictionary. Could you discuss as well what reaction you got from filmmakers and those mentioned in the book? And could you also relay the famous story of the film director Michael Powell writing to you?

DT: I got some reaction, if not a great deal. Bogdanovich loved the book. Of course, he was very well treated in the book, so it was easier for him to love it fully. I remember a party in San Francisco at which John Schlesinger refused to talk to me because of what I had said about him. I remember a lot of people over the years like Paul Schrader, Martin Scorsese, and Robert Towne—all of whom I knew quite well for a while—who liked the book.

Nothing, though, was on par with that one morning at Dartmouth in my office in Fairbanks. I received a handwritten letter—black ink on cream-colored paper, four pages as I remember—from Michael Powell. I have the letter somewhere.

I had never met Michael in England. He had found the dictionary, or someone had shown it to him, and he wrote and said how touched he was. It was a great letter and the start of an enormous friendship. I wrote straight back, and, although he was retired by that time, we quite quickly got to a point where I was asking him if he’d ever be interested in coming over to Dartmouth and doing something. Almost instantaneously, he wrote back, “Yes, of course! When?”

Things moved quickly. We pulled together a little bit of a budget. The Hopkins Center was very good about it. Peter Smith, who was the director of the Hopkins Center, found some money. We floated the idea, and it was approved, that Michael would come over and somehow teach a course in filmmaking.

It turned out that Michael was very interested in trying to do a film from a novel by Ursula Le Guin. He said, “Why don’t we do an extract from that film?? We did so, and we shot it on 35mm. He came to campus in the winter of 1980, arriving in a pink Harris tweed suit. He was, you know, a great, eccentric character. He possessed absolute assurance. He was not really interested in the academic process per se, but I think he knew that if he acted the way he wanted, bright students would learn a great deal from it, which is really what happened. They shot an extract, and it was an amazing time. We also ran a series of his films, and he began writing his autobiography while he was at Dartmouth. [Powell begins his autobiography by writing of his surroundings in his room at Dartmouth, looking out onto East Wheelock Street, in January of 1980. -Ed.] His presence on campus was a major event in the lives of people who went on to big careers, like Chris Meledandri of Illumination. Meledandri actually made a film about Michael at Dartmouth, a short documentary.

Michael’s visit caused film to rise in the general consciousness at Dartmouth. It had previously been a minor thing, a part of the Drama Department, but while I was there, film became a recognized major—a specific concentration within the department. And it was on its way to being a serious department on its own footing. I would say that Michael was crucial in that. He was unaware of what he was doing to the school, but he was doing a great deal.

He was also decisive in my life in the sense that we became very friendly. I remember a certain point at which he said, “Well, David, how long are you going to stay at this school?” I said, “Well, Michael, I’m not sure. I don’t have much money of my own, so I’m not sure what I’m going to do.” And he said, “Oh, you should be making plans to leave. How long do students stay here?” And I said, “Well, they reckon to get through in four years.” And he said, “You should do the same.” He was therefore instrumental in my leaving Dartmouth. He saw that there were other books I had to do.

Administrative duties at the College had been getting to be quite a big chore in my life. I had been told that I was likely to be Chairman of the Drama Department, which I was not cut out for at all. Really, I wanted to write and be more involved in making films, that kind of thing. So, by 1981, I left Dartmouth. So, in fact, I was there just over four years. But it was a very great time, a very important time for me.

TDR: I should think as well that your inviting Michael Powell to Dartmouth was instrumental in his life as well. It facilitated, I think I may say, an extraordinary reappraisal and celebration of his career. And there’s also the story of Martin Scorsese and Thelma Schoonmaker. Would you be able to relay that story? Were you the one who introduced him to Scorsese?

DT: He had met Scorsese before—at the Telluride Film Festival, I believe. But Michael came to me one Friday and asked me, “David, how do I get down to New York quickly?” I told him about the airline that went down out of West Lebanon. And he said, “Okay, because I think I’m going down. Marty has invited me. He’s cutting Raging Bull, and I’m going to sit in the cutting room with him.” Michael did just that, and that’s where he met Thelma Schoonmaker, who ultimately became his wife. So, Michael’s visit to Dartmouth was a big turning point for him, too.

TDR: Today, of course, Michael Powell is held in considerable esteem, and he is certainly one of the most represented filmmakers in the Criterion Collection. But at that juncture, I daresay you and Scorsese were perhaps his stalwart champions, certainly in this country. Is that a fair assessment?

DT: I believe he had a number of partisans, but it was not a high point in Michael’s career. Marty’s encouragement did much more for him than I could ever do, but I did have a part, I think, in the revival of how his career was viewed.

Courtesy of Dartmouth Archives

TDR: In leaving Dartmouth, were there specific books you already knew you wanted to write, or was your departure born of a more general calling that you felt?

DT: I had a very crowded life. In addition to the Dartmouth job, I was asked by The Real Paper in Boston, which was an alternative newspaper, to be their film critic. And I began to be their film critic at almost exactly the same time that I was teaching, which led to a crazy life. I would finish a class at Dartmouth, let’s say at four o’clock in the afternoon. My wife would pick me up. We would drive down to Boston, which was a two-and-a-half-hour drive. We would see a movie, a press screening. She would drive back, and, while she was driving back, I would write the review in the car. And the next morning, when I was back in class teaching, she would telephone the interview to the editor at The Real Paper. It was insane, and it went on for about a year. It made, again, for a crowded life.

I liked the teaching very much, but I didn’t enjoy everything else that one had to do. I’m sure I’m not the only teacher who would say that. I knew that I had to break out of it and find more time for my writing. So, when I left Dartmouth, it was a very fruitful time. We came to San Francisco, and I met a lot of people who were very important in my life, like Tom Luddy, whom I mentioned earlier. One of the other, really great friendships I made was with the filmmaker Bob Rafelson, who was a Dartmouth ’54. Over the ensuing years, I visited him on several of his films, and I knew him quite well up through the end. He was so far from a classical Dartmouth student—a very rebellious, difficult, belligerent guy.

Anyway, upon arriving in San Francisco, I started to write a different kind of book. I would say that I had written English books before, if you know what I mean. I was now writing American books. And I wrote a book called Suspects, which got published in 1985, and it is one of the most original types of books that I’ve written. Doing it was a giddy experience, a wonderful experience. It suggested that I was more than just a film academic. I was never really, in my heart, a film academic, and Suspects was the book that made that clear.

TDR: It’s interesting that you underscore this distance from academe. In addition to Suspects, itself a divergence as you say from the rather more academically oriented books that you’ve authored, you also have been a writer of film reviews for newspapers—not just The Real Paper but also The New York Times, among others. My point is, I think, that I consider it a different matter to be a writer of books on film history and a critic in the more traditional sense for newspapers regarding films on first release. How, then, did you conceive of your career trajectory before and after your move from New Hampshire to San Francisco?

DT: Oh, that’s a great question, if a complicated one. When I went to film school, I saw myself becoming a filmmaker. And I’ve been involved in filmmaking on and off all along. But by the time I left Dartmouth, I was really clear in my head about wanting to write about the way in which film was not simply a business or an art. It didn’t fit into those handy, tidy academic frameworks and labels. It was an ocean in which we were all trying to swim. It demanded something larger than a single focus. Suspects really demonstrates that idea. It’s a book about how we all live and have lived in a world in which the imagination has been expanded by the coming of film. Pursuing that sort of premise was my cause and my calling much more than anything I had ever encountered before.

Yet I continued to write scripts. I wrote a script for Scorsese, which was a very enjoyable experience. It didn’t get made, although I think it helped lead him to Casino. It was about Las Vegas, which my wife and I love and is a totally insane, very American place. I wrote a book about Nevada eventually.

TDR: Altogether, you’ve written a good deal of what I would deem “topic” books—in recent years, on the art of acting, on directors, on how best to watch films. Do you find that these are topics which have intrigued you at different points in your career? Or are they all various components of how you have long viewed cinema, and you’re merely working down your internal list, as it were?

DT: The most important thing for me, or for you in trying to get a handle on me, is that I’m a totally obsessive writer. I write every day, and if I don’t write in a day, I feel it. The process of composition is very important to my composure and my stability. So, I need to write, and broadly speaking, the way film has changed us is my subject. I need to turn this obsession into something that earns a bit of money, so I write books that I can sell, and books that publishers very often ask me to write. But the central theme of all of them is more or less the way in which film has changed our participation in reality—the way we live a much more imaginary life than once was the case.

TDR: Film is a changing medium, and the media landscape is dramatically different from what it once was. What trends do you see or anticipate among the younger generations?

DT: I entered film school in 1960, and I had no sense of it then, but later I realized that there could not have been a better moment to start it. Hollywood was breaking down and changing, and increasingly there was an enormous influence of foreign films.

It was a great, great time. The people one had first encountered as writers in Cahiers and Positif suddenly began making films that were clearly some of the most interesting films being made at the time. It was the age of Godard, you know. There was also a fervor to know more about films, which meant that Americans started looking at their old films.

Ford, Hawks, Lubitsch, and others suddenly came back into fashion. Now, I believe that urge has gone away on the whole. I would say that people are much more concerned with what’s on the screen tonight. Film and television, the image, the screen, has become so central to existence that a lot of people really don’t have time for going back to the past.

I say this with sadness, but it’s inevitable, I think. We’re being led into a culture in which it’s less easy and less useful to talk about the arts and more necessary to talk about media. You can’t reverse that. You may regret it, and you may say, if only you’d look at The Shop Around the Corner, you’d learn more about life than you will from anything you might see today.

People do what they feel they must do, and that’s always been part of the history of cinema. I’m not totally unhappy about not being around for too long to see what’s going to happen. I’m not optimistic about it, but that’s in the nature of being old, you know. But I do think there’s always the chance that someone’s going to come along and do something quite good and different. A part of me still hopes that will happen.

TDR: Thank you once again, Mr. Thomson, for taking the time to talk with The Review.

DT: Thank you.

Hello! I was Arha! The dancer in this project of Michael Powell’s! I would love to talk with anyone who was involved in the project. It remains my fondest childhood memory. Thanks!