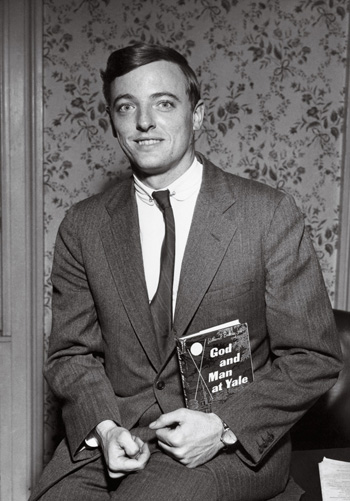

Seventy years ago this month saw the publication of William F. Buckley, Jr.,’s first book, God and Man at Yale. A fierce critique of his alma mater and its increasingly alarming socio-political predispositions, Gamay, as Buckley called it, decisively launched him into the public eye. This earliest published work of the late conservative luminary has become available once again, in stores and online, in a 70th Anniversary Edition. This edition features a retrospective introduction penned afresh by conservative commentator and Yale graduate Michael Knowles. Mr. Knowles ruminates upon some Buckleyan history and dismisses as left-wing myths both liberals’ ostensible fair reception of Buckley and Buckley’s supposed reluctance to offend. To be sure, the publication of Gamay marked a watershed moment in the history of combative conservative opposition to a prevailing left-wing orthodoxy, in this case at Yale. So too do the origins and compositional purpose behind Gamay parallel The Dartmouth Review’s own mission through the years: to hold Dartmouth’s Administration accountable and to seek the preservation of those aspects of the Old Dartmouth which are essential to any undergraduate’s experience at the College.

It is thus that I find myself writing this piece on Buckley, who himself saw in The Review a kindred spirit, serving on its advisory board from its 1980 inception through his death in 2008. Over the course of this twenty-eight-year period, Buckley was an ardent supporter and patron of the paper, consistently defending it on the national stage despite the many controversies which it provoked. In 2005, he even spoke at The Review’s 25th Anniversary Dinner, held in Manhattan, where he pointedly observed that the paper continued to fight against educational trends in which “tradition and piety are scorned, injustices sociologized, … the state glorified, [and] patriotism patronized.” However, this is only one great Buckley quote on the subject of The Review. Yet another can be found on page 2 of each of our print editions; in this quote he asserts that The Review is a “vibrant, joyful, provocative challenge to the regnant but brittle liberalism for which American colleges are renowned.” Such an assessment is not inconsistent with that which Buckley himself set out to accomplish with the publication of Gamay seventy years ago.

Certainly, the overwhelmingly leftist inclinations of Yale—or, for that matter, of Dartmouth and most every other college and university—are hardly unknown or surprising today. However, in 1951, Yale was still broadly viewed as the custodian of a certain conservative tradition (in contrast with Harvard, for instance, whose earlier shift far to the left was more or less manifest). Hence, Buckley’s book functioned as something of a public revelation, divulging and censuring before a nationwide audience those forces active at his alma mater which were contributing to a sizable leftward push. In Gamay, the most destructive force that he outlines is unquestionably the considerable subscription to “academic freedom” (the ironic quotes are his). Buckley posits that this term, as employed by academics, is only a guise, a manipulation, even, of a scholar’s responsibility to educate. It serves to shield these academics from any objections to the way in which they teach or even what precisely they teach.

Thus insulated, explains Buckley, members of Yale’s faculty were becoming sufficiently empowered to depart from the university’s traditional values and in turn communicate to students the idea that all philosophies, attitudes, and views ought to be considered of equal worth and merit. Readers today might be reminded of the journalistic error known as “false balance,” in which greater balance is portrayed as existing between opposing viewpoints than is actually supported by the evidence. Buckley objects vigorously to such an understanding of “academic freedom,” asserting that while academics should have the right to unconstrained scholarship, the same should not hold true for their teaching. Rather, says Buckley, alumni and parents have the right to demand that Yale insist upon the purveyance by its faculty of a particular “value orthodoxy”—namely, one in favor of individualism (as well as, by extension, capitalism) and religion.

It is interesting to note the ways in which his position here departs from the typical, modern conservative’s opinion on the subject of higher education. Buckley himself acknowledges conservatives’ emerging tendency—with which he emphatically disagrees—to desire purely neutral education, with no preference revealed in instruction towards individualism or collectivism, religiousness or atheism. Today, one hears this precise sentiment expressed perhaps most frequently as a form of conservative rallying cry against indoctrination: a demand that colleges teach students “how to think, not what to think.” However, Buckley holds that “value inculcation” to students, by way of the gentle counsel of earnest and erudite professors, is itself of great import in teaching students “how to think,” particularly when under the aegis of the traditionally American values embraced by alumni and parents.

Indeed, while Buckley does stress in his book the importance of exposure to works and beliefs of all perspectives, he essentially goes above and beyond that which most conservatives today endorse. Whereas modern conservatives advocate neutrality in the values transmitted in education, Buckley writes of his desire to maintain a steady inculcation of those values upon which his alma mater and, for that matter, this country were founded. In reading this, one cannot help but be reminded of present-day legislative efforts throughout the country to institute “patriotic education,” which efforts we are constantly told amount to nothing more than fascistic escalations of an ongoing culture war. Then again, perhaps modern conservatives’ broad adoption over the years of a position in favor of “educational neutrality” is indicative simply of some elemental acclimation to the long-lasting, left-wing bias in education.

In any event, I am confident that today one would have more success in lobbying for the inculcation of individualist values than that of religious values. That Buckley writes in favor of imparting religious values marks an intriguing but perhaps outdated argument from the perspective of modern education. Certainly, many of the nation’s oldest colleges and universities, including Yale and Dartmouth, were founded by Congregationalists (and still others by groups attached to different Christian denominations) with the intention of conveying and instilling the ideals of religion. However, the character of these institutions has been so greatly secularized over the years that it has become noteworthy if they, like Dartmouth, even retain chaplains and offer to interested students various religious communities and groups in which to take part. Moreover, the philosophy commonly known as secular humanism has so firmly taken root at these institutions that any values related to morality which they might wish to convey are today probably viewed as peripheral to religion.

Buckley also discusses the existence of entities that could serve to advance his cause and whom parents and alumni could lobby in a campaign promoting value inculcation. Specifically, he writes of a college president and upper-level administration that were hamstrung (or otherwise none the wiser) as to Yale’s considerable political about-face while being, themselves, fairly conservative, assuredly capitalist, and pro-religion. One of Buckley’s main objections lies with the inaction of these administrators in setting straight a portion of the faculty. Today, one cannot imagine a student at Dartmouth—or any other major university or liberal arts college—being able to speak familiarly as to anything approximating a traditionalist administration.

One finds that the college administration of today, or certainly Dartmouth’s administration, occupies itself predominantly in the task of issuing impulsive, left-wing pronouncements. The frequency with which these declarations are released suggests that even the most passionate progressives likely find themselves scrambling to catch up. The only logical conclusion is that the administrations of Dartmouth and other institutions are “virtue signaling” to their overwhelmingly left-wing student bodies. Presumably, like so many other corporations today, they are desperately attempting to escape criticism of their capitalistic business practices. Hence, they are seeking to co-opt and appease young people’s current social justice fervor.

In the above précis, I have endeavored to describe several points of significance which arise in the book, and I have then made an effort to discuss the sort of consideration that one might grant to them from the modern perspective. Whether in fashioning linkages or in recognizing the marked differences between education in 1951 and education today, it is fascinating to read and reflect upon early iterations of the bias which has so thoroughly pervaded academia. While there are undoubtedly many respects in which Gamay today constitutes a text that is outmoded, altogether Buckley’s first book has surely not lost its topicality. On the contrary, from my perspective, it remains an essential read for all who possess an interest in American college education. The insights which William F. Buckley, Jr., tenders in God and Man at Yale have proven especially prescient and intriguing to reconsider. I strongly recommend a purchase of this new 70th Anniversary Edition.

Be the first to comment on "Buckley, Yale, and The Dartmouth Review"