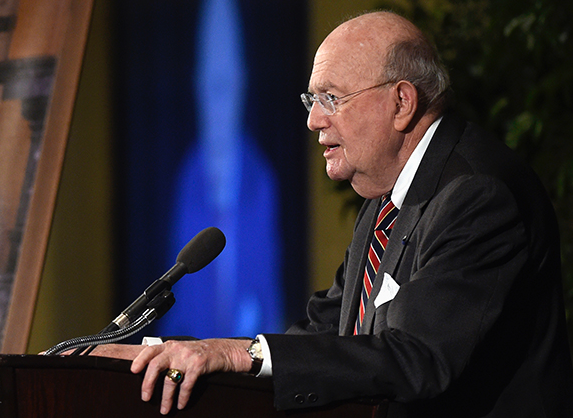

On Tuesday, September 20—to commemorate Constitution Day (September 17)—Dartmouth’s Nelson A. Rockefeller Center hosted Hon. Laurence H. Silberman ’57, Senior Circuit Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, for a talk in Filene Auditorium entitled “Free Political Speech Under Threat: Eisenhower Would be Ashamed.” The event was reasonably well attended, although, to be sure, the audience was an older one, populated in large part by denizens of Hanover, members of the Class of 1957 (for whose sixty-fifth reunion Judge Silberman was in town), and a sprinkling of Dartmouth’s faculty. Student attendees were, unsurprisingly but still conspicuously, few and far between. (Heaven forbid Dartmouth’s countless law school aspirants attend a Constitution Day lecture by one of our nation’s finest jurists.) That said, I was pleased to see that outgoing Dartmouth president Phil Hanlon was in attendance.

The Rockefeller Center is to be congratulated for having invited a jurist—and a conservative, no less—of Silberman’s stature to deliver an address on the occasion of Constitution Day. (Silberman has sat on the D.C. Circuit since 1985, and he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2008 from President George W. Bush, who lauded him as a “guardian of the Constitution.”) It is, to be sure, not often at all that one gets to hear a presentation from as thoughtful and insightful a legal theorist as Judge Silberman.

The judge’s talk also proved a welcome departure from last year’s (at least comparatively) underwhelming Constitution Day lecture, delivered by the Dartmouth Department of Government’s very own Professor Sonu Bedi. While a friendly and accessible speaker who has evidently been a student of the Constitution for many years, Professor Bedi’s lecture last year offered only a trite subject of discussion—the friendship of the late Justices Scalia and Ginsburg—and a rather silly call-to-unity argument that “living” and “dead” theories of the Constitution are reconcilable. Although he is forty years Professor Bedi’s senior, Judge Silberman delivered a talk that was at once more energizing and more informative. Ultimately, Silberman established himself as not just a student of the Constitution but an authority.

In his twenty-five minute address (which was followed by a thirty-minute question-and-answer period), Judge Silberman advanced the thesis that the First Amendment’s protection of free speech is not merely a legal doctrine but the embodiment of American democracy’s most fundamental value—and that he has come to “fear the strain on the First Amendment’s guarantees” in today’s political climate. This is particularly unfortunate, Silberman declared, because toleration of free political speech has always been the crucial unifying factor in our nation.

The judge proceeded to offer an historical overview of the First Amendment’s creation, its incorporation to the states (via the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause), and the landmark Supreme Court cases in which it played a part. In so doing, Silberman not only demonstrated an outstanding capacity for historical reflection and analysis but evinced a strikingly originalist judicial philosophy. I particularly enjoyed his consideration of Madison’s drafting of the First Amendment. Silberman suggested that “freedom of speech [emerged as] a necessary corollary of freedom of the press … it follow[s] apodictically, if you protect words that appear in the press, you [can’t] suppress those words uttered verbally.”

In much the same vein, Silberman went on to decry judges who “constitutionalize” questions that ought to be addressed or indeed solved by elected legislatures. His criticism to this end was a potent attack on judicial activism—that is, the propensity of judges and justices to engage in rank policymaking from the bench. For those not terribly well versed on the matter, I will add that judicial activism is dangerous in that it turns federal courts into super-legislatures. In effect, unelected lawyers appointed to the bench seek to attain their own desired outcomes in cases rather than seek to correctly interpret and apply relevant law irrespective of the outcome. Silberman made an off-hand reference to Jefferson, and this reference was well taken: judicial activism is truly the epitome of Jefferson’s concept of judicial tyranny.

Judge Silberman also pointedly expressed his support for overturning New York Times v. Sullivan, the 1964 Supreme Court decision that established the ‘actual malice’ standard in public figures’ lawsuits against media. He described the decision as “wholly illegitimate policymaking by the Supreme Court.” Many in the audience likely did not expect to hear a sitting federal appeals judge, even one on senior status, speak this strongly in favor of overturning longstanding Supreme Court precedent.

As an aside, I will note that Silberman has in fact been very outspoken on this subject. He even articulated his anti-Sullivan argument in a dissent that he wrote last year, in which he infamously called the The New York Times and The Washington Post “virtually Democratic Party broadsheets” and declared that “nearly all television—network and cable—is a Democratic Party trumpet.”

With the precision that only an appeals judge of his caliber could muster, Silberman outlined for his Dartmouth audience what was, in effect, the legal reasoning that justifies his desire to overturn this nearly sixty-year-old precedent. The decision rendered in Sullivan was (I) “contrary to text and history,” he said; and (II) it has proven unworkable (it has “created new problems for society … the media can [knowingly] spread false rumors”). Silberman also defended his anti-Sullivan position against First Amendment-inspired criticism by simply, and effectively, explaining that a free press is not necessarily an all-powerful press.

Silberman next decried the infringements on free speech perpetrated by the U.S. government during the McCarthy era. He emphasized the import of the fact that two Republicans, Maine Senator Margaret Chase Smith and President Dwight Eisenhower, were chief among those who brought McCarthy’s reign to an end. The judge cited Eisenhower’s famous Commencement Address at Dartmouth, from the spring of 1953 (a few months before Silberman matriculated), in which he powerfully levied an impromptu attack against McCarthy’s speech-suppressing, fear-inducing tactics:

[W]e have got to fight [communism] with something better, not try to conceal the thinking of our own people. They are part of America. And even if they think ideas that are contrary to ours, their right to say them, their right to record them, and their right to have them at places where they are accessible to others is unquestioned, or it isn’t America.

Having repeated this compelling Eisenhower quote and paid his own due deference towards condemning McCarthy’s horrid tactics, Judge Silberman bluntly stated that he believes we are faced today with an even worse threat to free speech than that which McCarthy presented. “Some political speech [today] is attacked as if it were blasphemy,” Silberman declared, “drawn from the colonial period, when witches were burned at the stake.” Moreover, threats against political speech “come dishearteningly, heartbreakingly, from young people, influenced by academics, [who were] ironically … prime targets of the McCarthy era.” Indeed, Silberman said, restrictions on free speech have emerged pronouncedly from academic institutions, and particularly the Ivy League.

At this point, Judge Silberman addressed the elephant in the room: his most recent attention-garnering act, or rather the occurrence which precipitated it. In March of this year, students at Yale Law School—the highest-ranked law school in the nation—attempted to shout down a public, bipartisan dialogue between a conservative and a liberal lawyer, who were both supporting unrestricted free political speech. In response to the students’ actions, Yale’s administration penned a letter that halfheartedly valorized free speech but also, said Silberman, highlighted a need “to celebrate respect and inclusion … whatever that means.”

As for Judge Silberman’s media-attracting feat, after the issuance of this response from Yale’s administration, Silberman availed himself of the federal judiciary’s listserv to articulate his own response. In an email blast to all Article III judges, Silberman sent a blistering advisory note:

The latest events at Yale Law School in which students attempted to shout down speakers participating in a panel discussion should be noted. All federal judges—and all federal judges are presumably committed to free speech—should carefully consider whether any student so identified should be disqualified for potential clerkships.

Next in his lecture, Judge Silberman enumerated other offenses against free speech which he believes the Ivy League has committed: (I) At Princeton, Professor Joshua Katz was stripped of his tenure and fired after criticizing a faculty letter that demanded preferential treatment for minority faculty and students. (II) At Harvard, Professor of Economics Roland Fryer, who is black, was suspended after undertaking empirical research that challenged present consensuses on race. (III) At UPenn Law School, when Professor Amy Wax mentioned “mismatch theory” (which criticizes affirmative action), she sealed her own fate. (IV) And finally, at Dartmouth, the College Republicans’ Andy Ngo event this past academic year was canceled by the Administration due to unspecified information shared by the Hanover Police Department. Adding insult to injury, the College Republicans were charged security costs for an event that did not take place. “It is inappropriate for the College to ever charge organizations for the protection their speech requires,” Silberman said. “That policy simply encourages those who want to cause as much trouble as possible.” Ultimately, he said, the College “aligned itself with those who wish to silence speech by canceling the event.”

He continued, doubtless cognizant that President Hanlon was in the audience: “I hope and expect that Dartmouth’s new president, Beilock, will have the steel in her spine that is needed to take this responsibility seriously and stand up for free speech when it becomes difficult. Her recent statements have been encouraging. But when the chips are down, many university presidents have folded.”

Judge Silberman concluded his lecture by returning to the subject of Joseph McCarthy, bitingly suggesting that “the charge of racism, not unlike McCarthy’s frequent cry of communism, has been drained of much of its meaning.” Ultimately, Silberman called upon all Dartmouth students and administrators to refuse to accede to censorship and conformity.

It was perfectly evident throughout his speech that Judge Silberman had no qualms about verbalizing his true thoughts. The thirty-minute question-and-answer period that followed lent only further confirmation to this end. Charles Wheelan, a Rockefeller Center policy fellow, was the designated interrogator, and he asked questions of the judge that he had personally written and other questions that he had collected by way of note cards from the audience. Wheelan did reasonably well in asking questions of Judge Silberman, although I do note that the judge (often quite hilariously, and with full confidence) scoffed and dismissed out of hand some questions as well as some of Wheelan’s added commentary. I thought it was especially illuminating when Silberman balked at Wheelan’s suggestion that Supreme Court decisions serve as the “instruction manual” for judges on the various Courts of Appeals. Indeed, Silberman—whom The Wall Street Journal’s Editorial Board recently called maybe “the most influential judge never to have sat on the Supreme Court”—showed that he has no interest in waiting for guidance from the justices.

Neither, for that matter, is Judge Silberman concerned with placating sensitive politicos. In the first place, Silberman took further swipes at Dartmouth and President Hanlon, including by suggesting that “building community” is merely another pretext for suppressing free speech. He also staunchly defended the Dobbs decision, predicted the reversal of the First Circuit and overruling of Grutter v. Bollinger (2003) in the current Harvard admissions case, and sang the plaudits of Chief Justice Roberts’ justly famous phrase from his 2007 Parents Involved decision: “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”

My personal favorite of Judge Silberman’s responses was when he ridiculed a question from an audience member as to whether event protestors’ shouts couldn’t also be considered political speech worthy of protection. In a sudden flash, Silberman retorted that, “if you think … the protest shutting down a speaker is free speech, then you’ve created a reductio ad absurdum, [and] that’s ridiculous. That’s like arguing that screaming ‘fire’ in a crowded theater is free speech.”

Judge Silberman was an outstanding speaker, doubtless the best I have seen at a Rockefeller Center event in my time at the College. His talk was intellectually rigorous and highly engaging, and I am confident that his jurisprudential prowess will continue to exert tremendous influence both within the judiciary and without.

I am saddened to hear that Judge Silberman just passed away but gratified he was able to give this talk and thank you so much for the write up.