With the Hopkins Center for the Arts still cautiously under-booking performances, the College has forced Dartmouth students to broaden their search for cultural enrichment. Fortunately, the performing arts scene in the Connecticut River Valley is roaring back to life after a dark hiatus during the pandemic. The recent arrival of the renowned Dorrance Dance company to the Lyndon Institute and Catamount Arts in St. Johnsbury testifies to this rural artistic revival. Dorrance Dance, which is based out of New York City and led by MacArthur ‘Genius’ Grant recipient Michelle Dorrance, is the first professional tap dance company to perform in the area since 1983.

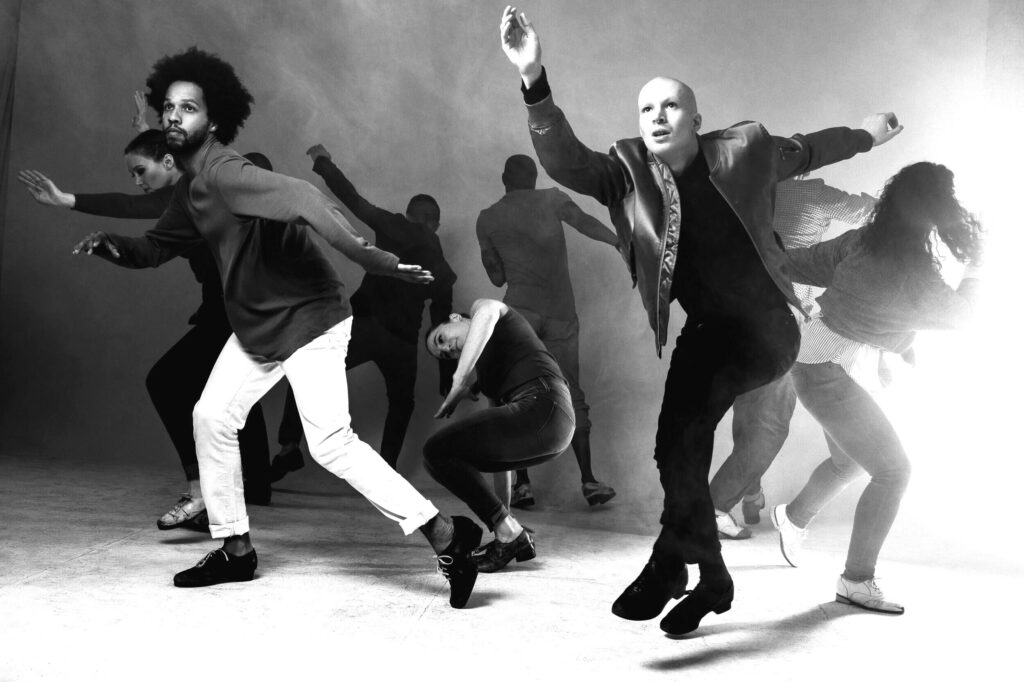

To be honest, I have little exposure to tap dance, professional or amateur. But my unfamiliarity with the form did not prevent me from grasping the exceptionality of Dorrance Dance’s performance, “SOUNDspace.” Dorrance’s troupe created soundscapes of unexpected variety by experimenting with improvisational body percussion, such as slapping and patting other parts of the body in addition to the standard footwork, which offered softer beats, and the use of alternative dance surfaces like leather, wood, and metal. In one act, two dancers tapped on a platform textured with a jar of sand, creating a rhythm of soft, grainy screeching—though a most unusual noise, it was actually quite pleasant. Most of the performance had no accompanying instruments or music beyond these variations of percussive dance, but the tasteful deployment of Greg Richardson on the upright bass added a rush of fresh aural flavor at precisely the right moments to keep the audience enthralled.

The high point of the performance was a true tour de force of Michelle Dorrance’s chorographical prowess. Placed at all corners of the theater and immersed in complete darkness, dancers flanked the audience with a tastefully disorienting audio-spatial experience. The performance was delivered with flawless synchronicity.

Dorrance, however, views her role as a choreographer as considerably less important to the outcome of each performance. “I create the skeleton of the performance, but there is plenty of room for improvisation. My dancers still get to play,” Dorrance explained during a question and answer session following the show. Improvisation is key because, to Dorrance, “tap dance is a subversive form. Rooted in protest and transcendence, improvisation and innovation were paramount to its survival and are innately embedded in its very foundation.” Her choreography makes explicit space for her performers to incorporate their own experiences into the dance. Dorrance insists on the importance of creating that space because she sees it as a way to respect and honor tap dance’s origins.

Tap dance, and percussive dance more broadly, grew out of the West African drumming tradition. That tradition was forcibly and violently imported to the Americas through the transatlantic slave trade, but it was altered by the oppressive constraints that slave holders placed on Africans. Seeing the potential for drumming to be used as a clandestine form of communication between slaves, slave holders often banned percussive instruments. Movement as music emerged as a way to retain vestiges of drumming culture through these inconceivable hardships.

The history of percussive dance is further complicated by its appropriation in minstrel performances as an imitation of slave culture for the entertainment of white audiences. While minstrel shows played a distasteful role in incorporating tap dance into mainstream American culture, the legendary black tappers and ‘hoofers’ of the jazz era presented a dignified and empowering alternative. Dorrance drew inspiration for her work directly from these torchbearers of the black percussive dance tradition, some of whom served as early mentors to her.

In her childhood, Dorrance trained at the Ballet School of Chapel Hill in North Carolina with tap master Gene Medler, who introduced her to the greatest living jazz era tap masters. Starting at only eight years old, Dorrance studied with Dr. Cholly Atkins, Clayton Bates, and Miss Mable Lee, to name a few. These experiences formed her commitment to the black legacy of tap dance.

Following her award-winning pieces, “The Blues Project” (2013), which depicted the history of the blues through tap dance, and ETM: The Initial Approach (2014), which fused tap with electronic sounds, Dorrance won a MacArthur Fellowship. Her ‘genius’ grant recognized her role in “reinvigorating a uniquely American dance form in works that combine the musicality of tap with the choreographic intricacies of contemporary dance.”

“SOUNDspace” is arguably Dorrance’s most innovative and confrontational work. She spent that last year revising the choreography of previous versions performed before the pandemic. She expressly ties the changes she made to the Black Lives Matter protests and subsequent riots last summer—an event she calls “the revolution.”

Even so, the politics of the performance seemed relatively subdued to an indiscriminating observer such as me. In all honesty, I thoroughly enjoyed the tap, irrespective of its revolutionary potential. As my first live performance since before the pandemic, I could not be more pleased with “SOUNDspace.” Nor could I be more grateful to Catamount Arts for its part in ending the cultural famine that has gripped this area for the last year and a half.

Be the first to comment on "Review Reviews: Dorrance Dance"