Bissell Hall, along with the rest of the Choates, was built in 1958 on the playing field of the Clark School, which Dartmouth College had acquired five years prior. The Choates were the first major buildings built under Dickey and, to our unending shame, introduced Modernism to the hitherto picturesque campus. Bissell Hall of the Choates was named after another Bissell Hall—a two-story red brick gymnasium with bowling alleys, gymnastics hall, and suspended track—which had been funded by Bissell himself. Bissell, at the end of his career, had become a wealthy philanthropist. In donating a gym to Dartmouth, Bissell insisted that the gym include six bowling alleys “in remembrance of disciplinary troubles into which he had fallen as an undergraduate because of his indulgence in this sinful sport.” The building throughout its lifespan would also be the home of the Thayer School laboratories beginning in the early 20th century. The gymnasium was eventually demolished in 1958, making room for the Hopkins Center. Bissell Hall stood in the area that is now the main entrance and paved plaza outside the HOP.

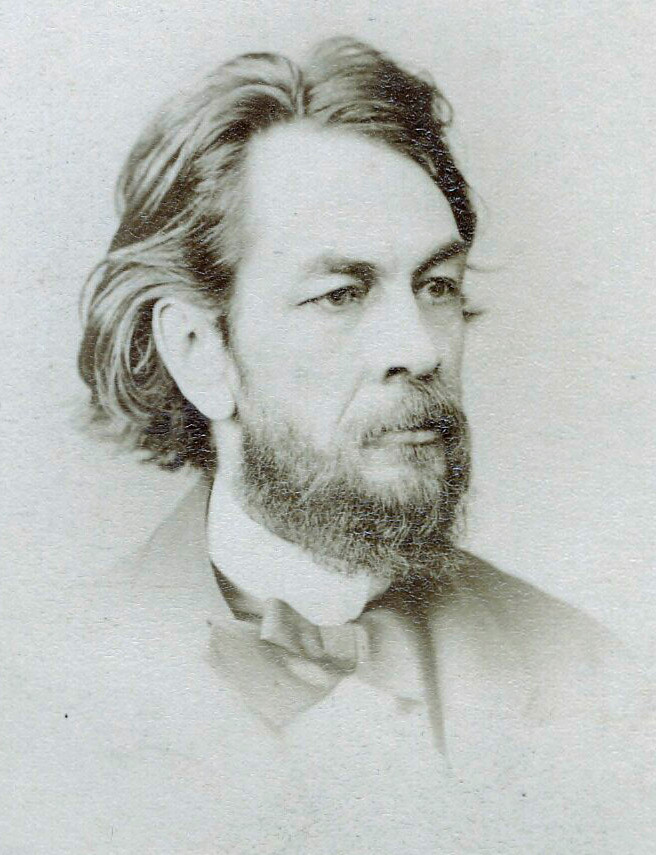

George Henry Bissell was born in Hanover, New Hampshire on November 8th, 1821. Like many Dartmouth men that preceded and succeeded him, Bissell paved his own, unique and unexpected path to enormous success. Though nowadays we associate the oil industry with Texas and the American South, “The history of petroleum,” as put by the New England Historical Society, “would never have happened without Yankee ingenuity…”—ingenuity that sprouted from a little college on the hill in rural New Hampshire. Though no one man founded the American oil industry, in his he was nevertheless considered one of the founding fathers of the burgeoning industry. George Bissell was the world’s first oil baron and built the infrastructure needed to support the entire operation (including barrel-making, railroads, banks, hotels, and insurance). He was and is widely praised for his acumen, intelligence, integrity, and honesty. Neil McElwee wrote that, “Among the great oil pioneers of the first decades, Bissell was a giant. The oil men recognized it was Bissell’s early vision, initiative, unwavering commitment, personal sacrifice, proven integrity, and fifteen years of entrepreneurial risk that put the American oil industry on its feet. The oil men and writers of the nineteenth century as one recognized George Bissell as the patriarch of their industry.”

Bissell’s father was a fur trader who died when George was twelve. “From that time on,” writes McElwee, “Bissell was left to his own intelligence, talents, hard work, and self-reliance to make his way in the world.” He worked his way through Dartmouth by teaching and writing articles for newspapers. He graduated in 1845, achieving a notable distinction in literature as well as in ancient and modern languages. After graduating, he taught Greek and Latin at Norwich Academy and traveled around as a journalist. This would eventually lead to Bissell winding up in New Orleans, where he became a high school principal and then superintendent of schools, all the while studying languages and the law whenever he had any free time. By 1853, Bissell was in New York, practicing law at on Wall Street.

Nobody expected Bissell, least of all himself, to become world’s first oil baron. The story begins with a visit home in either the fall of 1853 or summer of 1854. Bissell was visiting his mother and stopped by the college, paying a social call to Dr. Dixi Crosby, at that point Dartmouth’s professor of surgery and obstetrics. During this visit, Bissell noticed a jar labeled “rock oil” on the doctor’s shelf. Crosby told Bissell that another alumnus, Francis Brewer (Crosby’s Nephew and also a physician), had brought the oil to Dartmouth. Brewer’s father, Ebenezer, was a wealthy timber baron. Perhaps Bissell should thank Dartmouth’s strong alumni bonds for his eventual success. Accounts differ on Bissell’s initial enthusiasm for the black liquid, with some writers stating that Bissell had an acute perception into the liquid’s potential as a cheap light source, with others writing that Crosby had to push the goo onto the uninterested New York City lawyer.

Regardless of the events in the intermediary, Bissell, with his law partner J. G. Eveleth, purchased around several hundred acres of land from a Titusville, Pennsylvania lumber company in 1854. This purchase set the stage for the start of America’s petroleum industry. The lumber property was filled with oil springs, some of which was being used to lubricate sawmill machinery. At that time, the oil leaked out of the ground (called seep oil) and was soaked in blankets, which were then drained over barrels. Initially, this oil was marketed as “Seneca Oil” named after the local Indians who shared its supposed healing properties with settlers.

At the outset, Bissell and Eveleth couldn’t sell their company stock. Though they were getting oil by digging pits and ditches, the oil was being sold to patent medicine companies. Investors just were not confident that Bissell’s black liquid would prove a valuable resource in any form outside of pseudo-medicine. Enter Yale chemistry professor Benjamin Silliman, at that time one of the nation’s preeminent chemists. His father of the same name had developed a process that enabled the commercial production of kerosene. Being a college professor, Silliman was expectedly underpaid. He agreed to write a report about the commercial potential of the black goo for some sum between $500 and $1200, which included laboratory testing fees. He concluded that Bissell’s petroleum could not only be used as lubricant, but as lighting fluid, writing to Bissell that “the Oil of your Company [has] a much higher value as an illuminator than I dared to hope.” This report on “rock oil,” carried out by a poor professor, would go on to become one of the most famous consulting reports ever produced.

Bissell had played a keystone role in starting the oil craze and wasn’t about to be pushed to the wayside. Fighting through unscrupulous investors in New Haven, internal corruption within his company board of directors, and backstabbing lawyers, Bissell never gave up. Even when the New Haven men secretly created a new company without Bissell and transferred the legal property to it, Bissell started again from the bottom. With help from New York investors, Bissell dived headfirst into this newfound passion of his, investing heavily in purchasing and developing oil farms and property around Pennsylvania. In addition to developing these oil fields, Bissell developed railroads with millions of dollars of out-of-state capital. When oil and bank panics hit the Oil Region in 1866, Bissell opened his own bank, George H. Bissell & Co., betting on the viability of the still young but struggling oil industry. By the end of his career, he would have overseen the Hoover and Stewart Farms, the Clapp farm, the barrel factory, the Central Petroleum Company, Buchanan farm, Reed Well, Farmer’s Railroad, United Petroleum Farms, the George H. Bissell Express Company and the George H. Bissell Bank. These enterprises comprised an oil industry in their own right. Each of these endeavors would have been nearly overwhelming for most men. Bissell, never to be average, started all of them and stuck with all of them, a feat not short of superhuman.

Due to a life of nearly nothing but constant hard work, Bissell fell ill in 1878, rarely leaving is home until he passed away in November 1884. He was laid to rest in Hanover, New Hampshire beside his wife and mother, escorted by the Dartmouth College faculty and student body.

Be the first to comment on "Striking Oil in the Choates"