Dartmouth’s longstanding relationship with the Telluride Film Festival—held annually in Telluride, Colorado—was forged through the efforts of the late Bill Pence, co-founder of that festival and latterly Dartmouth’s Director of Film. Mr. Pence’s legacy lives on in the tradition that he begot: Each September, the College exhibits a selection of some six or seven pre-release films that received screenings at Telluride earlier in the month. This year marked the tradition’s thirty-sixth installment.

The films in the “Telluride at Dartmouth” series have historically been screened in the Hopkins Center’s Spaulding Auditorium. However, that space has been unusable since January 2023 due to a broader project of renovation (to date, primarily demolition) of the Hopkins Center. Therefore, in a departure from previous years, the six films in this year’s series were screened next door in the Black Family Visual Arts Center’s Loew Auditorium. This space, newer and rather more comfortable than Spaulding, is the namesake of the legendary Arthur M. Loew ’21(h), who served as president of Loew’s, Inc., the parent company of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Unfortunately, this change in venue led to a considerably reduced availability of tickets. While Spaulding had a capacity of 900 patrons, Loew can accommodate only 237. As a consequence, tickets sold out far more quickly and consistently for this year’s slate of films than they have in the recent past. This trend ensued despite the fact that exiled Hopkins Center officials had increased the number of screenings to be held for most of the films to three (from two in previous years). Some tidy math: Three showings in Loew aggregate to just 80% of the capacity at one showing in Spaulding.

The six films screened at this year’s “Telluride at Dartmouth” were a noble lot—I enjoyed five of the six films considerably. Thanks are due to the Hopkins Center’s Director of Film Sydney Stowe.

The following reviews are presented in the order in which the films were screened at Dartmouth.

American Symphony, d. Matthew Heineman

Matthew Heineman is a Dartmouth alumnus, a member of the Class of 2005, but in this column I can extend no hometown privilege. His documentary American Symphony might aspire to thoughtfulness, but it emerges as a decidedly incongruous, perplexing, and even false affair.

The film takes as its subjects the multi-talented, award-winning musician Jon Batiste (late of the Stephen Colbert show) and his partner, later wife, the author Suleika Jaouad. Heineman juxtaposes Batiste’s mounting career success with trauma that arises in his personal life: Jaouad learns that her leukemia, in remission for a decade, has returned. Batiste and Jaouad now must navigate his burgeoning career, her resurgent illness, and their own relationship. Meanwhile, Batiste must work to compose the film’s eponymous symphony, which is commissioned—in the wake of his ever-brightening stardom—by none other than Carnegie Hall.

The major issue plaguing Heineman’s film is that these disparate narrative threads fail to join together into a cohesive whole.

American Symphony strives for profundity through its dual focus on Batiste’s public and private lives, but Batiste himself fails to provide justification for what Heineman intends to be a nuanced portrait. On the contrary, Batiste comes across as superficial, often just plain silly, in most of what are supposed to be his “private” musings and interactions. He is, perhaps, overly aware of the camera.

Jaouad is far and away the one who draws our sympathy, not simply due to the trying ordeal that she must endure but because of the genuine feeling that she shows for Batiste. For his part, Batiste is obscure and unreadable. He perpetually exhibits what can most favorably be described as a sort of stoicism. In the film’s many phone conversations between the pair, it is seemingly always Jaouad who calls Batiste, not the other way around. When on the phone with Jaouad, Batiste never says much, if anything. When he visits her in the hospital, he does not ask questions of the doctor, leaving that to Jaouad and her mother.

Is such detachment, perplexing as it is, a roundabout way in which Batiste deals with trauma? There’s really no way of knowing, as Heineman does not proffer an answer. Is Batiste in fact unidimensional, or was Heineman just unable to direct Batiste to be his true self? I’d wager it was the latter, which left Batiste unsure of himself before the camera. To be sure, Batiste’s persona in private, as the film depicts it, does not much depart from his stilted persona on Colbert’s late-night show or during public-facing moments in the film itself.

It is also a matter of pure contrivance that Heineman focuses on the “American Symphony” to the extent that he does. His attempts to filmically realize Batiste’s process of composing the symphony are bizarre at best: We see Batiste discuss ideas for passages with haphazard groups of musicians and bark loose compositional orders to an accommodating, masked transcriptionist who seems to do all the work. Then come various rehearsals and, ultimately, the Carnegie Hall concert. But what do the symphony and the concert have to do with anything else in the film? The concert hardly offers a climax, as there is no climactic parallel in Batiste’s private life, which is of course the object of the viewer’s real interest. A “technology failure” that Batiste ostensibly experiences during the concert, which is said to necessitate improvisation, is a laughably feeble attempt to inject some importance and tension into this part of the film.

A late scene in which Batiste, Jaouad, and a group of friends go sledding perfectly encapsulates the film’s problems. It’s apparent that the sequence has been artificially conceived, and never do we learn who the friends are. The scene apparently depicts Batiste’s first time sledding, for which he’s nominally excited, but he looks uncomfortable and miserable.

American Symphony is a product of calculated artifice that reverberates all too loudly. I award one star.

The Holdovers, d. Alexander Payne

Paul Giamatti is a great character actor, and I’m always pleased when he nabs the occasional plum leading role in a film worthy of his talents. I am happy to report that Alexander Payne’s The Holdovers falls into this rarefied group, while Giamatti falls into Academy Award territory.

Giamatti portrays Paul Hunham, a pompous sourpuss of a teacher who presides over classes in “ancient civilizations” at an elite, all-boys New England boarding school called “Barton.” (Groton, anyone?) Hunham relishes in teaching with an iron fist and in failing donors’ laggard children—he views himself as a bulwark against the erosion of academic standards. His martinet’s ways may be excessive, but among Barton students, stupid, hostile, and entitled egotists are in fact well represented.

Hunham is not just abrasive and inconsiderate but also rather a sad sack: stodgy, antisocial, and derided by his students and fellow teachers alike. This set-up is roughly a ’70s American take on Terrence Rattigan’s great The Browning Version.

It comes as little surprise to us when another teacher’s falsified excuse leads the headmaster to task Hunham with supervising five students who have to stay at the school during Christmas break. In fulfilling this duty, Hunham proceeds with no small degree of scorn, and we in turn become accustomed to the terse dynamics which prevail among these five students and their keeper. But then four of the students seize an opportunity to leave; the fifth, Angus Tully (Dominic Sessa), is unable to do so because his mother and stepfather can’t be reached. The film thus suddenly becomes a story of the relationship between those who still remain at Barton—the grumpy Hunham; the moody only child Tully; and the school’s meditative cook Mary Lamb (Da’Vine Joy Randolph).

It’s Christmastime, and we find that these three souls are all in pain during a season in which they should be delighting and finding joy. But over time, they grow closer, or at least begin to understand one another. So too do we begin to understand.

A scene at a Christmas party, which Hunham reluctantly attends, is outstandingly constructed: Events unfold in such a way that we palpably feel Hunham’s deep-seated heartache as well as Lamb’s tremendous grief for the recent loss of her son. On this happiest of occasions, hurt is drawn out to its most pronounced.

The three gradually grow closer, and each eventually attains some measure of closure during a trip that they together undertake to Boston. In particular, Hunham and Tully learn a good deal about each other—that each has experienced profound hurt and trauma in his life. Each even begins to indulge the other, and Hunham grows protective of Tully. In navigating the many highs and lows of the character, Giamatti essays the part brilliantly, segueing between Hunham’s hurt, rancor, and (ultimately) verve with ease and to great effect.

Payne (b. 1961) is a sensitive director whose works have long taken rather self-conscious inspiration from the 1970s cinema on which he was weaned. But significantly, The Holdovers marks Payne’s first foray into that period from an historical perspective, and it’s a unique historical film if ever there was one, operating as it does on multiple levels.

Narratively, it’s hardly revisionist; it’s a cracking ’70s film that happens to have been made a half century after the fact. Tonally, it presents a potent blend of comedy and drama that is of a piece with the best of New Hollywood filmmaking. It also happens to have been shot in 35mm using ’70s lenses and equipment (the film grain flickers splendidly), and it is possessed of a lovely, muted color scheme. It could have been made by Hal Ashby sometime in between The Last Detail and Being There. In short, The Holdovers is the sort of film that Payne wishes he could have made in the 1970s, and he has thus sought to realize that wish in the fullest way possible. This is not merely an historical film but a time capsule to an earlier, grander era of filmmaking as a practice.

The Holdovers is an exceptional film on all counts and is eminently rewatchable. I am inclined to deem it a masterwork, and indeed I award four stars.

Poor Things, d. Yorgos Lanthimos

Poor Things is a phantasmagorical, steampunk comedy-horror directed by the great Yorgos Lanthimos (The Lobster, The Killing of a Sacred Deer, The Favourite). Perched narratively somewhere between Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein and George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, the film is nothing less than a raging tour de force of genre transcendence.

In retrofuturist Victorian England, Willem Dafoe is Dr. Godwin Baxter, a brilliant surgeon and anatomist whose own monstrous physiognomy signals wherein his scientific interests lie. À la Dr. Frankenstein, Baxter retrieves and reanimates a corpse, that of a young woman (Emma Stone) who killed herself by leaping into the Thames. Naming her “Bella Baxter,” Godwin and his awkward young assistant Max McCandles (Ramy Youssef) then work to educate her in motor skills, speech, manners, and general knowledge. And so they begin to echo Shaw’s Henry Higgins, growing attached to the girl under their tutelage as she progresses. Godwin comes to consider her his daughter—Bella reciprocates and refers to him in a paternal (if distinctly ironic) sense as “God”—while Max develops romantic feelings for her.

As Bella matures, however, she hungers to explore and experience the world. Thus, when a roguish lawyer named Duncan Wedderburn (a stellar, threatening yet comedic Mark Ruffalo) manipulates his way into meeting her and offers to take her on a faraway journey, she eagerly accepts. Godwin is more self-aware from the outset than Henry Higgins ever becomes: He realizes, despite Max’s protestations, that he must not obstruct Bella from leaving.

So she does, alongside Duncan, and during their varied journeys she encounters astounding locales—effectively different miniature worlds—and makes assorted friends. While the film thus becomes something of an adventure, what is most significant is that Bella undergoes substantive intellectual and emotional growth on her trek. That is, she learns for herself the way in which things work, in lieu of being taught it. To this end, Stone gives a wonderfully layered performance that well demonstrates a sort of incremental learning by way of experience.

Poor Things’ cinematography is the stuff of visual splendor. The film opens with expressive black and white, but when Bella embarks upon her travels with Duncan—and her world expands beyond the confines of Godwin’s house and immediate environs—the film transitions to deep color with an amber hue that recalls the best of three-strip technicolor.

Lanthimos creates strikingly fantastical, controlled environments for his characters to inhabit. Godwin’s house is a world in and of itself, a scientific marvel of creatures and technology accentuated by dreamlike camera lensing and angles. But the worlds—the other countries, retrofuturistically depicted—through which Bella travels are truly stunning to behold, blending era- and country-specific aesthetics with outlandish technology. These worlds nonetheless have a projected artificiality that is diegetic to the film. Bella realizes this, looking out from a café balcony onto the dying poor below, in a defining moment that punctuates her ever-expanding consciousness.

At long last, Bella arrives back in England, where she spends the film’s final fifth—an effective “coda,” to my mind, that attends additional explanation from Godwin of how he created her. Ultimately, the film ends in a manner that is strange, ironic, and perhaps somewhat low-key, not at all in the epic fashion that Bella’s lavish and drawn-out Continental travels might suggest.

Poor Things is a stunning film, Lanthimos’ best, and as innovative and memorable in its content as it is in its form. I award four stars.

The Promised Land, d. Nikolaj Arcel

The Promised Land is at a certain level an old-school epic, something that might have been made as a big-budget Western in the United States fifty years ago. But this Danish film transcends what received expectations may exist for such a genre by way of a profound sense of place, period detail, and an awesomely compelling central performance.

The film stars the great Mads Mikkelson, who admirably retains his connections to the Danish film scene even as he appears in major Hollywood productions. Its director is one Nikloaj Arcel, with whose other work I am unfamiliar, but who succeeds widely here.

Arcel’s film centers on Ludvid Kahlen (Mikkelson), a poor, retired army captain of low birth who, in 1755, arrives on the barren Jutland heath to cultivate the land. In the event he succeeds, government leaders have promised him (however apathetically) that he will win a title of nobility and financial reward from the king. However, his goals promptly place him in conflict with a local aristocrat, Frederik de Schinkel (Simon Bennebjerg), the largest landowner in the area, who does not want to lose his considerable power to a prospective elite of even vaster land ownership.

In due course Schinkel intimidates Kahlen’s workers off of the heath, but a resourceful Kahlen responds by negotiating for the participation of local highwaymen, through whose labors he may continue his cultivation project. His crop: potatoes, resilient to cold weather and well suited to the Jutland’s sandy soil. That Schinkel is fanatically despotic, even insane, substantially heightens the film’s intensity—we know he will not desist. As we see, he maltreats and even kills tenants and household staff as a matter of practice.

At its heart, The Promised Land is a story of ambition and the law. Kahlen is a self-made man who desires to advance himself further still, while Schinkel is the son of a self-made man, who exploits legal provisions that can be made to work in his favor. Indeed, Schinkel struts about flanked by a legal advisor and claims that the hearth belongs to him, not to the king. Kahlen’s resolve and potential success at cultivating the land pose a threat, above all, to Schinkel’s ability to exploit the legal system. And so the film does not present a conflict within and without the aristocracy so much as a legal conflict, however extrajudicially fought through most of the film.

But while Schinkel can escape consequences for departing from legal courses of action, Kahlen cannot, and a group of landowners led by Schinkel ultimately resolve to secure Kahlen’s execution by prosecuting him. Interspersed scenes in the film of the king’s advisors indifferently dismissing Schinkel, his plans, and at this moment his prospective execution are quite distressing.

The Promised Land is pictorially epic and staggering, which serves to underscore at once the brutal violence depicted and the opulence and extravagance of Schinkel’s way of life. The film also foregrounds well—through Kahlen’s stoicism, which proves highly emotive for the viewer—the changing extent of Kahlen’s ambition and his valuation of a potential family life.

The film is an engrossing piece of cinema, and I award four stars.

Fallen Leaves, d. Aki Kaurismäki

The Finnish film Fallen Leaves, by the director Aki Kaurismäki, is a wonderful work that evokes a gentle sensibility rooted in the twentieth century.

Its story focuses on two quiet, middle-aged people, Ansa (Alma Pöysti) and Holappa (Jussi Vatanen), both of whom hold small jobs which are for them largely hollow, vapid affairs. These are people who go through the motions to make ends meet.

Ansa works stocking shelves in a supermarket, but she loses her job when a surly security guard reports her for taking home expired food. Later, she meets Holappa, an habitually despondent construction worker, in a karaoke bar. They exchange fleeting glances but have minimal contact. Neither of them is especially forward.

Ansa gets another job, working off the books as a barmaid and dishwasher for a small pub, but her employer is arrested on the morning of her payday. Yet thereupon she and Holappa find one another again; in a short time they’re on a date at the cinema, and things go well. But circumstances conspire several times over, and a relationship, it seems, might never be able to take root between these two needful souls.

I consider the film one of the great analogue movies of our time, and not just because it was shot on 35mm. It is extraordinary that so much in the film hinges on modern technology, or rather the absence thereof from the main characters’ lives. Ansa does not have a computer and must rent one to search for a new job. She also regularly listens to the radio, receiving updates on the Russia-Ukraine war, a depressing topic if ever there was one. Moreover, Ansa and Holappa do not know each other’s names for the duration of their date at the cinema. Their sole means of contact afterwards is Ansa’s phone number, scribbled on a piece of paper (of all things) that she gives to Holappa. But unbeknownst to him, the wind proceeds to lift it out of his pocket and carry it away. He no longer has her number and thus has no way of contacting her: a follow-up date is impossible to arrange.

That they fail to exchange names before or during their date at the cinema is, of course, a contrivance, but it’s a sufficiently fanciful one to be diverting. It also demonstrates further still the lonely quiet in which each has long existed and which has come to define each of their lives.

In wonderful nouvelle vague fashion, Fallen Leaves also features to great effect posters and other representations of old films and music albums that are thematically related to the lonely romance at hand. To that end, as Ansa and Holappa stand in front of the cinema, there is perhaps most notably a poster for David Lean’s Brief Encounter.

The film harkens to cinema of the past in other ways too. Ansa adopts a dog, whom she names Chaplin, and his comfort, however silent, is appreciable. And finally there’s a late-stage parallel to Leo McCarey’s An Affair to Remember.

Fallen Leaves most often uses refrains from Tchaikovsky’s 6th Symphony as its extradiegetic music, but during a long walk at the end of the film we hear overlaid a Finnish rendition of the song “Autumn Leaves.” It’s an appropriately enchanting ending to a lovely film, whose middle-aged lonelyhearts are echoes of the twentieth century. I award three-and-a-half stars.

Anatomy of a Fall, d. Justine Triet

The winner of the Palme d’Or at Cannes, Justine Triet’s Anatomy of a Fall is a successful courtroom drama that fully embraces that which has long soured critics and audiences on the genre: deliberate pacing. The film’s title is, of course, a reference to Otto Preminger’s great (if likewise deliberately paced) courtroom drama Anatomy of a Murder, and Triet’s film is similarly effective in layering suspense and ambiguity into a web of investigations, attorney-client conferences, and courtroom oration and testimony.

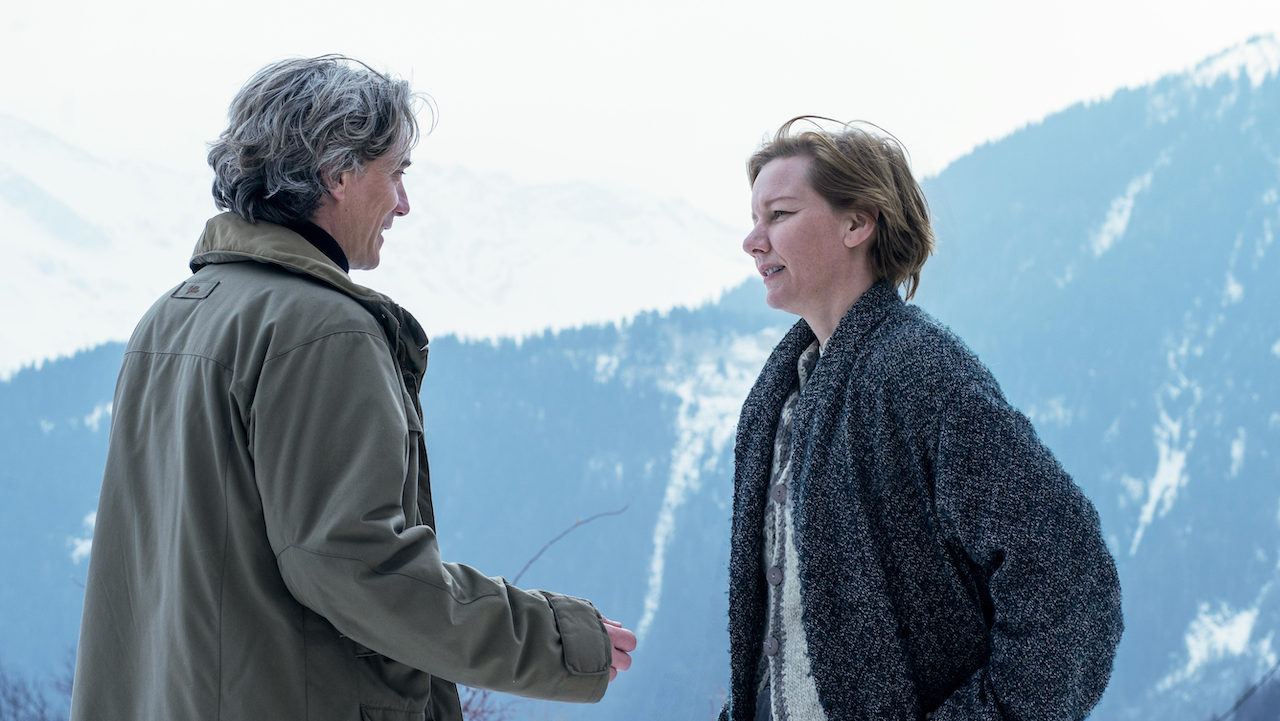

The film takes place in the French Alps, where German-born English author Sandra (Sandra Hüller) lives with her French husband Samuel (Samuel Theis), himself an aspiring author.

While Samuel is blasting music and doing construction work in the attic, Sandra tries and fails to give an interview to a university student writing about her books. As she attempts instead to take a nap, the couple’s son Daniel (Milo Machado Graner) leaves to walk the family dog, Snoop. These are the circumstances—the simple facts, that is—as we see them unfold. What we don’t see, we discover with Daniel upon his return to the house: His father has fallen from the attic window and lies dead on the ground, his head badly bloodied. Was this a terrible accident, or did Sandra push him? That’s the question about which a jury of Sandra’s peers is soon convened to hear evidence and deliberate.

Sandra enlists as her lawyer one Vincent Renzi (a wonderful Swann Arlaud), an old friend who may yet be in love with her. He prepares well for the trial, asking her for full explanations and seeking to reconstruct Samuel’s fall with the aid of a blood-spatter expert. And once the trial is underway, he defends her enthusiastically.

The trial itself unfolds as one of those crazy French legal affairs that the Americans and Brits can never hope to understand. It’s conducted in an inquisitorial style, in which seemingly anyone can say or ask anything at any time, several witnesses can be examined at once, and speculation is permitted ad nauseam.

Although attention is paid in court to the mechanics of Samuel’s fall, the prosecutor devotes most of his energies to painting a picture of Sandra and Samuel’s marriage as antagonistic—and of Sandra as having domestically abused her husband and engaged in infidelity. She and Vincent then proffer an alternative view. The film thus presents, in effect, an anatomy of a marriage.

For his part, Daniel—considered an unreliable witness due to his partial blindness—is largely relegated to the position of having to listen to the trial as it progresses. But in the end he proves to be considerably enterprising.

When the jury deliberates in the film’s last few minutes, ours is no more privileged a position than theirs in rendering a verdict.

Anatomy of a Fall is intellectually fascinating. Its treatment of literature (the métier of both Sandra and Samuel) as a subject, of its production, and of its inherent blend of truth and fiction is profound, particularly in the context of a trial whose very goal is to distinguish truth from fiction. I award three-and-a-half stars.

Be the first to comment on "Telluride Comes to Dartmouth"