There are two kinds of writers in this world. One is a bona fide intellectual, a philosopher who digs around the universe in search of all the answers. This writer is somewhat pretentious and often ignorant of the realities of human experience (imagine a reclusive philosopher, contemplating the world but not living in it). The other is an artist. While writing a novel, he thinks not about all the theories ever postulated but about his earthly exploits and the emotions they elicit. Sure, he is not as widely read or scholarly, but his genius is equally valuable.

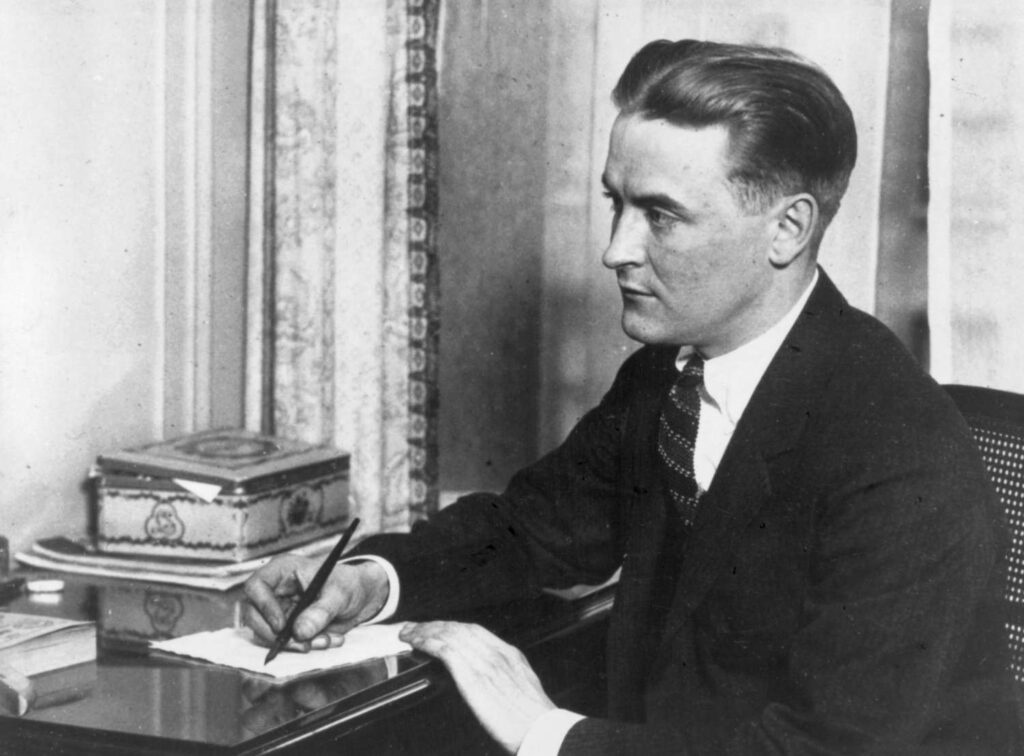

Robert R. Garnett’s most recent book, Taking Things Hard: The Trials of F. Scott Fitzgerald, expertly exposes the great American novelist as the second type of writer. The book is part biography, part literary analysis. Garnett, a professor emeritus of English at Gettysburg College and a Dartmouth ’69, links Fitzgerald’s tumultuous life to the characters and tragedies of his own stories. Garnett not only reveals Fitzgerald’s inspiration but posits an explanation for the author’s decline after The Great Gatsby’s publication. An extravagant, intoxicated lifestyle gave the world Gatsby, but it also wore down its creator, hampered his productivity, and ended his life at 44.

It becomes increasingly clear in reading Taking Things Hard, if it were not before, that Fitzgerald roared through the Twenties with his equally exuberant wife, Zelda. Gatsby remains the ultimate literary representation of the era because it is grounded in reality.

Fitzgerald’s magnum opus is taught to high school students as a commentary on wealth, class, gender, race, and every other social problem subject to political debate today. But far from setting out to chronicle the age’s political implications, Fitzgerald was simply putting his personal heartache and longing into story form. As Garnett underscores, Fitzgerald was an artist, not a social critic. This sets him apart from, say, John Steinbeck, whose The Grapes of Wrath took aim at life in the Depression-era.

Today, English departments are infested with theorists who seek out hidden Marxist meanings in our great novels. They read between the lines, look for things that have never truly existed in the text, and turn writing into a science. In effect, they are well-educated conspiracy theorists. It reminds me of a quote attributed to Flannery O’Conner, who criticized academics for searching for non-existent symbols and metaphors instead of appreciating stories for what they actually say. No, the color of the character’s hat doesn’t always mean something. Novels should be about humans, and not everything about humanity can be explained or summarized through theory. Sometimes messages cannot be put into words, only experienced.

Garnett’s interpretation of Gatsby is attuned to this idea. Fitzgerald’s classic is a book deeply rooted in his own experience with women—the longing and heartbreak are Fitzgerald’s own. When we look at Fitzgerald the man, we see clearly that Garnett’s thesis is convincing. Fitzgerald was a simple guy, who spent his days ruminating on women and football. He was not a modernist intellectual but an eternal undergraduate who overindulged in booze.

Certain tidbits about Fitzgerald that emerge in the book are quite humorous. While rising as a writer, he once said that all American literature between the Civil War and the First World War was insignificant. That period, as Garnett points out, included Mark Twain, Henry James, and Robert Frost, to name a few. Somewhat full of himself, Fitzgerald approached writing with little respect for the canon to which he would later contribute. He was also in a subtle rivalry with Ernest Hemingway. They would frequently criticize each other’s works, even the soon-to-be masterpieces. However, we shouldn’t mistake Fitzgerald for an intellectual elitist with legitimate, theoretical challenges to these authors. He was just human, with personality and eccentricity.

Eventually, tragedy overcame the comedy in his life. Fitzgerald never ceased the binge drinking of his Princeton days, and, though they had a lot of fun together, his marriage to Zelda did not last forever. Debilitating schizophrenia condemned her to a mental hospital; his various affairs never cured the longing in his heart. With Gatsby in the past, his personal struggles, which once were enough to inspire his genius, caught up with him.

It was at Dartmouth that Fitzgerald hammered one of the final nails into his own coffin. Hired to write a film script about our Winter Carnival, he traveled north to Hanover. A bender ensued, as chronicled by The Dartmouth Review (see “Fitzgerald Visits Hanover” on our website). He was soon fired from the job, which he desperately needed, and not long after he was dead. But we must not say that our College on the Hill ruined Fitzgerald. He had been on the descent long before his trip to Dartmouth.

The strength of Garnett’s book is that it peers deep inside Fitzgerald’s pain by examining his writings. Garnett has clearly read everything by and about the author. He adroitly connects experiences to characters and plotlines. Though a tough task, Garnett weaves biography and literary analysis seamlessly. The result is an honest interpretation of Gatsby and of Fitzgerald’s other writings. They were about life, love, and loss, not deeply theoretical social issues. The best writers don’t come up with a message and frame a story around it; like Fitzgerald, they live life, tell it as a story, and let it speak for itself.

Fitzgerald is best known for The Great Gatsby, but he was far from a one-hit-wonder. His many short stories hold some of his best thoughts. Having only read Gatsby and a short story called “Winter Dreams,” I was, before reading Garnett’s book, unfamiliar with his vast story collection. These stories are not something to overlook. To gain the most from Garnett’s book, I recommend that you read as many of Fitzgerald’s short stories as possible. Garnett assumes some familiarity with Fitzgerald’s work, and the more the better.

Garnett’s Taking Things Hard is an excellent contribution to Fitzgerald scholarship. Not only is it thoroughly researched, it also takes the proper approach. Garnett rejects absurd, far-fetched interpretations and offers the truth. If anyone should read Taking Things Hard, it ought to be English teachers. Teach kids to slow down, appreciate the emotion of a story, and revel in the artistry as such, because that’s what good literature is.

Absolutely beautiful piece! “No, the color of the character’s hat doesn’t always mean something…. Fitzgerald was a simple guy, who spent his days ruminating on women and football. He was not a modernist intellectual but an eternal undergraduate who overindulged in booze.” Spot on regarding Fitzgerald, but also so broadly apposite!