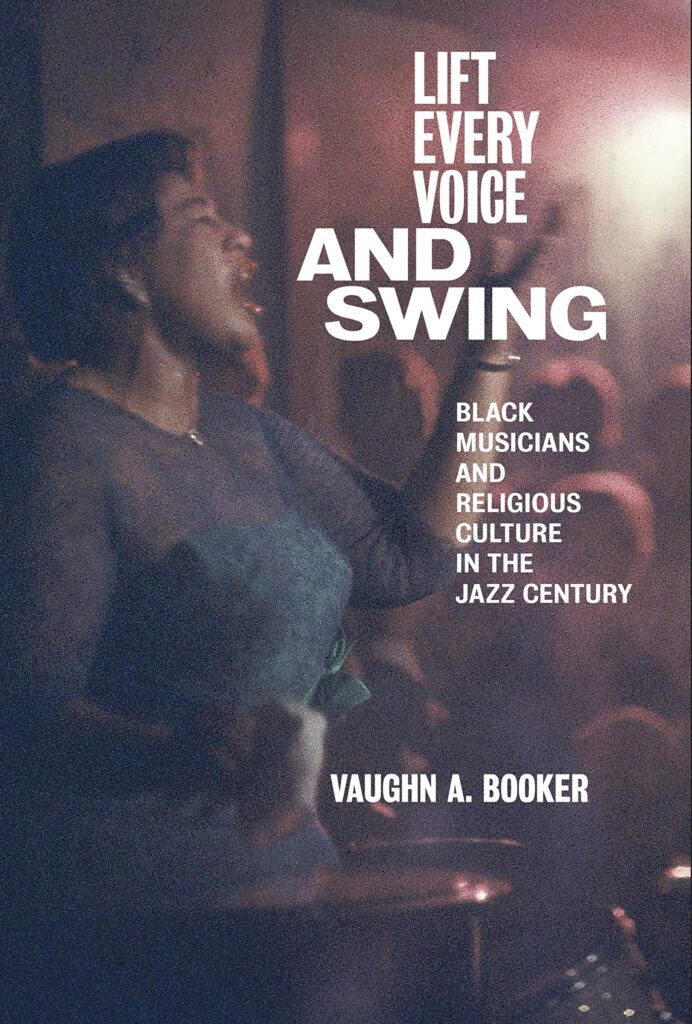

Vaughn A. Booker (’07), Ph.D., serves as Assistant Professor of Religion and AAAS at the College. Professor Booker’s recent work, Lift Every Voice and Swing (NYU Press), is an innovative study in which he demonstrates a facility for thoughtfully discussing topics that transcend the traditional contours of his own academic disciplines. He includes a wealth of fascinating biographical material, much of it previously unexamined, and delves into a polished discussion of jazz music.

Nevertheless, Booker’s focus remains squarely on religion. He explores African American religious authority in the Jazz Age, investigating the exertion of this authority within and upon the nationwide black middle class. He contends that the emergence of popular black jazz musicians in the 1920s and 1930s wrought a challenge to—and ultimately a transference of—traditional, principally Afro-Protestant religious authority. Indeed, he suggests that the most prominent of the then-emergent jazz luminaries inherited from official black religious leaders a broadly ecumenical authority, which led these musicians to occupy a position of substantial influence among professional and middle-class African Americans. Ultimately, Booker explains, the influence of jazz became so great as to provide to the black middle class a “competing venue for race representation,” apart from Christianity (27).

I must acknowledge that I am, without doubt, reviewing this work from a layman’s perspective. I am not a religion major, nor have I any particularly sophisticated understanding of American religious history. That being said, I do know something about jazz as a genre, and I am somewhat well acquainted with early jazz music and musicians. It is perhaps for this reason that I found Booker’s writing at its most engaging when serving to advance his thesis by way of various song and lyric analyses as well as commentaries on the often-complex relationship with religion of each of his principal biographical subjects—Cab Calloway, Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, and Mary Lou Williams. These are the moments that I enjoyed the most, as opposed to those parts of the book in which the trends of broad religious history are conveyed.

The book begins in such a manner, however, in both its introduction and first chapter. The former is winding and synoptic in nature; the latter, slightly less so. This first chapter describes the opposition of Afro-Protestant churches, and especially African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Zion churches, to jazz and swing music in the 1920s and 1930s. These churches’ ministers nonetheless wished to attract and retain parishioners, and thus, in an effort to remain culturally relevant, they gradually allowed jazz to appear in their services and at their social functions. Booker acquits himself well as he recounts the fruits of archival research which document this historical progression, in spite of the repetitious nature intrinsic to any series of extensive quotations from newspapers and other publications.

Booker then progresses to an examination of Cab Calloway, the comical, effervescent “hi-de-ho” man whose celebrated 1931 chart-topper “Minnie the Moocher” hardly suggests ample religious influence. However, Booker highlights Calloway’s commitment as an Episcopalian and pointedly submits that Calloway’s life and career in the world of entertainment bespoke a conviction that “religious irreverence was compatible with religious belief and belonging” (65). So too, Booker writes, did Calloway’s cross-racial appeal commendably tread a fine line: “present[ing] a form of humor about and for black people through jazz, but without permitting a designation of black people as essentially and enduringly ignorant and degenerate, as minstrelsy’s mockery offered” (66). Hence, Calloway was not just a generation-defining performer, but an influential race representative whose tempered mockery of overly stringent Christian convictions offered to the African American middle class a new pathway—one defined by a less extreme religious lifestyle.

Booker next turns his attention to Ella Fitzgerald, perhaps the greatest jazz vocalist of all time and certainly one of the most popular racial crossover artists in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. “Her career,” writes Booker, “became an effective vehicle for the desegregation of performance venues and the creation of integrated clubs, due to her popularity with white and black audiences” (81). This popularity was in no small part owing to the vibrant, joyful persona that she publicly exuded (despite an upbringing of destitution and maltreatment). But it was also because of her indisputable status as a major vocal interpreter of the Great American Songbook, which status firmly cemented her as an effective race representative. However, as Booker indicates, among the uninitiated, the ill-informed, or those with racialized expectations, one could mistake Fitzgerald’s singing voice for that of a white woman. He cites “[t]he expectations for black women to convey an authentic musical emotionality,” likely rooted in stereotypically soulful expressions of religiosity, which conflicted with Fitzgerald’s purity of voice and make-it-seem-easy vocal style (101). Fitzgerald’s restrained but joyful tonality, and indeed persona, signified a conscious embodiment of race representation that advocated the integrationist cause. But it also demonstrated, for the cause of African American public performance, a breadth of possibility that extended well beyond that of the stereotypical piety.

The next portion of the book is devoted to Duke Ellington, the renowned jazz pianist, composer, and big-band leader, and marks a return to a clearer exploration of religious authority and its influence on the African American middle class. Booker recounts Ellington’s conception of a racialized biblical past and a sacralized black history, which had an impact of some consequence on the fundamental nature of his compositions. Ellington’s respectful absorption into his music of elements from “classical” African American Christianity as well as “pre-Christian enslaved African religiosity” was highly influential (133). Indeed, his musical and poetic reflections of these sources stirred “romantic, pastoral imaginations” (132). Ultimately, such touching reflections signified to a broad swath of middle-class, protestant African Americans that the value of religion lies in “one’s capacity to think fondly and reverently” on the faith of one’s forebearers and to “practice their brand of piety in order to endure society” (ibid). Booker proposes that this fondness for black history—as conveyed and advanced by the ever-popular Ellington—became particularly significant upon the dawn of the civil rights movement, serving to confirm the import of jazz in the religious lives of middle-class African Americans.

In shifting to an interpretation of Ellington’s later career, Booker relies upon the composer’s private musings and annotations, which enable a discussion of the biblical lyrics that he began to far more freely and frequently write. Ellington’s dedication to composing “sacred music,” performed at concerts that were typically held in white churches, “indicated the prospect of interracial fellowship” and advocated the “integration [of] African Americans into [white] religious spaces” (185-186).

The work’s final bulk of biographical material examines the fervent piety of Mary Lou Williams, a jazz pianist and composer, whose inclusion in the book seems to me a strange choice. Williams was, in fact, something of an outsider to much of Ellington’s circle as well as a devout Catholic. I found the section on Williams to be out of place insofar as Booker’s thesis centers on specifically Afro-Protestant religious authority. However, there is certainly interesting reading to be found in Booker’s descriptions of both Williams’ missionary efforts, which sought to provide relief to needy musicians in New York, and her ardently pious compositions.

As the work nears conclusion, Booker provides some extraneous and more contemporary information, much of it relating to modern musicians and developments which occurred after the death of each of his four figures of biographical concentration. I personally thought this information was far less interesting than that found in the preceding chapters, although I do of course recognize the importance of acknowledging posthumous impacts in a biographically inclined text such as this.

Overall, Professor Booker’s study proves that his capabilities as a researcher and synthesist are indeed admirable. To this end, Booker’s thoughtful analysis and attention to detail are made manifest in this work, for his is an elaborate and insightful amalgamation of many different topics. While the book is predominantly written in the brooding and sometimes stiff academic tenor from which I often wish academics would depart, it is certainly one which should hold interest for students of jazz and religious history alike.

Very good!