The Hood Museum of Art’s latest exhibit, ““Men of Fire”: Jose Clemente Orozco and Jackson Pollock,” places the work of these two artists side by side to show how Orozco influenced Pollock. Orozco’s twenty-four panel, 3,200 square foot mural, “The Epic of American Civilization”, was painted in the early 1930s in the Reserves section of Baker library, and it’s no wonder that this sizable masterpiece had a pro- found effect on a young artist. Jackson Pollock visited the mural at our College in 1936 at the age of twenty-four, and the exhibit showcases the deep imprint Orozco’s murals left on him.

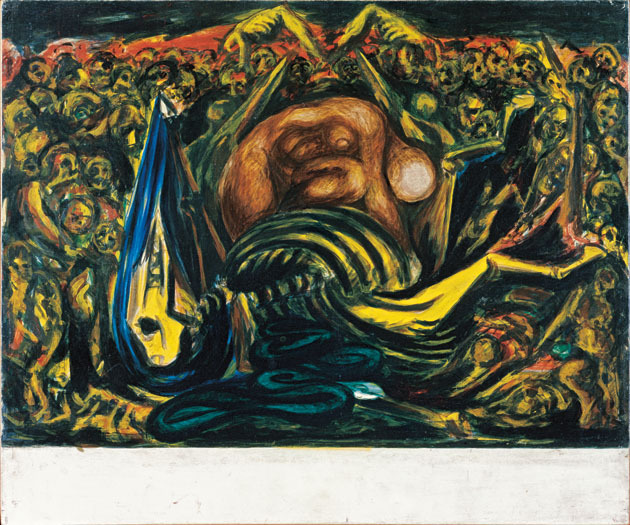

It was a pleasure to walk around the exhibit. The colors and figures were intense and striking, and both the thematic similarities and stylistic differences were interesting to observe. Both men were fascinated with fire, ritual, violence, and skeletons. The subject matter was either symbolic or literal and representative of opposing elements of destruction and renewal. Pollock was obviously struck by Orozco’s employment of primitive elements like violent sacrifices. Pollock thus reinvented many of the themes originally found in Orozco’s mural here at Dartmouth, but in his own creative style. Pollock’s works are no mere imitations of a role model, but evidence of inspiration that allowed him to develop his own artistic identity. There is the same aggression, vividness, and tension in Pollock’s paintings, but with more swirling motion and ambiguous figures.

Pollock’s art is far more abstract than Orozco’s bold, defined figures, although the Hood exhibit displays many clear examples of Pol- lock’s fascination with Orozco. Pollock’s paintings employ direct references to Orozco that are intriguing and certainly worth exploring for yourself.

Pollock’s “Untitled (Bald Woman w/ Skeleton)” is eerily similar to Orozco’s panel Gods of the Modern World, which depicts a skeleton birthing a stillborn child (representing dead knowledge) as academia looks on, criticizing modern institutional education. However, Pollock’s painting does not seem to be making any social or political statements, rather he simply was attracted to the motifs. After Pollock was placed in psychotherapy

for alcoholism, his psychoanalytic drawings frequently used bones, skeletons, snakelike creatures and hybrid animalistic figures, and the crucifix. His fixation with Orozco’s symbolic imagery is not for the sake of social criticism but a means of self-expression and battling his personal demon of substance abuse. This discovery is also furthered by the artists’ contrasting styles. Many of Pollock’s forms are unclear; the personal, emotional intensity of his pieces are more important than the definition and clarity that Orozco needs to send specific messages.

The exhibit compares Orozco’s panel “Cortez and the Cross to Pollock’s Composition with Flames,” demonstrating Pollock’s love for Orozco’s adoption of fire as a literal and symbolic force of both destruction and creation. If you search carefully, you can find a crucifix being licked by flames and clutched at by tangled figures amidst the bright, swirling colors. It’s visibly an incredibly different piece, but the thematic elements are the same. This happens also with Orozco’s dome fresco “Man of Fire” and Pol- lock’s pieces “Circle and Flight of Man.” Pol- lock’s pieces are more ambiguous and passion- ate rather than precise, but the pieces have the same shape and swirling motion. Another comparison made was between Pollock’s “The Flame” and Orozco’s “Gods of the Modern World” from his “Epic of American Civilization,” in my opinion simply due to a barely discernible horizontal skeleton. The Flame itself is a stunning piece, with flames licking the bones and evoking a sense of personal drama and devastation rather than a clear narrative scheme, but I see no true resemblance between this work and Orozco’s panel beyond similar preoccupations with primal themes.

“Men of Fire” successfully demonstrates how similar creative ideas can give rise to unique appearances. At first glance, these artists do not appear to have a strong link, but in examining their use of myth, ritual, sacrifice, violence and destruction, and creation and rebirth, it becomes clear that Pollock and Orozco are kindred spirits. Jackson Pollock utilized Orozco’s themes and imagery to find his own voice and artistic style. Pollock was also influenced by other artists; he came across Picasso’s famed Guernica around the same time. It may be more difficult to figure out what exactly is going on in a Pollock painting, but his range of emotions jumps from the canvas in a swirl of bright reds, oranges, and yellows, and deep greens, blues, and blacks.

Pollock’s chaotic artwork is just as striking and impressive as Orozco’s Epic of American Civilization, an immense mural that will always be housed right below King Arthur Flour in Baker Library. Jackson Pollock’s paintings and the Orozco sketches in preparation for his mural will only be enjoying each other’s company until June 17th. Although you’re not allowed to walk in with drinks from KAF (or anywhere else), it’s a small sacrifice to see massive figures participating in actual sacrifices at the hands of thrusting knives. Honestly, I tend to get the most excited over impressionist paintings of water lilies and bridges, but I thought this was a fantastic exhibit. The influence of Orozco’s Dartmouth mural on Pollock’s art is complicated and difficult to measure, making the exhibit all the more interesting. I’d certainly never seen anything quite like “Men of Fire”, and the two artists’ fiery works sharing wall space was really something to behold. Perhaps not such a great idea as far as museum dates are concerned, but don’t miss out. No matter what kind of art you’re into, this is at heart a stimulating discussion on the source of creativity, and I would recommend taking some time to immerse yourself in these works.

—Meghan K. Hassett

Be the first to comment on "Orozco and Pollock at the Hood"